Fighting for Our Military Community

As an Army combat medic, Jayme Hentig was accustomed to caring for wounded soldiers, even in the heat of battle. But in 2010, while on deployment in Afghanistan, his medical vehicle rolled over during a routine drive. He lost consciousness and woke up in a field hospital with brain and spinal cord injuries. In a moment, he was transformed from caregiver to patient.

Two years later, Hentig was medically retired from the Army. He slurred his speech, had regular seizures and was suffering from PTSD. He was told his cognitive abilities were permanently diminished and that he had exhausted all therapeutic options available. “Then it’s time to create more options,” Hentig thought.

As of 2019, more than 414,000 service members and veterans have suffered traumatic brain injuries or TBI. Hentig notes that’s nearly one in four military members.

“Every war has a signature injury,” Hentig explains, referencing the use of Agent Orange during the Vietnam War. “The big one for the War on Terror has been traumatic brain injuries.”

While many of those injuries are classified as mild, the long-term results, like headache, mood disorders, memory issues and increased risk of dementia, can be debilitating. Hentig watched as peers struggled to keep jobs. He felt compelled to use the mental abilities he still had to improve options for veterans like him.

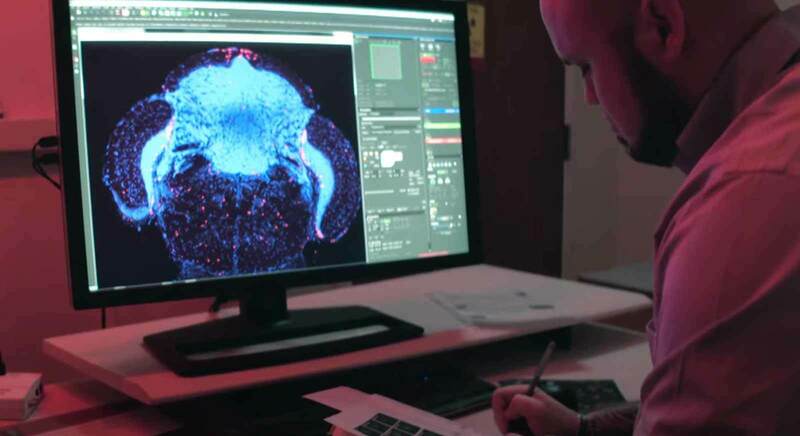

After earning his undergraduate degree in biology from Western Michigan University, Hentig came to Notre Dame as a doctoral candidate and joined the lab of David Hyde, the Kenna Director of the Zebrafish Research Center. Zebrafish prove a compelling study because of their ability to regenerate in ways humans do not. Hyde focuses on retinal degeneration, but Hentig proposed he look at the way zebrafish regenerate neurons after brain injuries — specifically, blunt force brain injuries similar to those experienced by military members.

After his first year, Hentig was awarded a prestigious National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship to fund his work, and in 2020 he was named a Tillman Scholar for his novel blunt-force TBI model. This model has been shown to mimic human pathologies and can provide new avenues to research injury progressions and regeneration. The model, Hentig says, will hopefully lead to the identification of gene regulation that provides neuroprotective and regenerative therapeutics.

Hentig isn’t the only veteran currently enrolled at Notre Dame. Today there are 100 veteran students across campus, in addition to the ROTC students and the family members of military service members. Regan Jones, the director of Notre Dame’s Office of Military and Veterans Affairs (OMVA), is committed to helping those numbers grow.

“My office is really helping build the bridge between the Notre Dame community in the military and veteran community, so that they can thrive here locally and we can support initiatives nationally, to ensure that they’re fully supported.”

Jones, a veteran of the Marine Corps, explains that today less than 1 percent of the American population serves in the military as opposed to 10 to 15 percent in previous generations. Because the network is small, a military-civilian divide has formed, he says, and many of the nearly 200,000 service members transitioning to civilian life each year don’t know about the opportunities available to them.

“For this experiment called democracy to work, we have to have these really brave men and women that all volunteer to serve our country in uniform,” Jones says. “We’ve got to do our part to make sure that when they return they’re fully integrated back into civilian life. The Notre Dame family is a part of that effort."

“My office is really helping build the bridge between the Notre Dame community in the military and veteran community, so that they can thrive here locally and we can support initiatives nationally, to ensure that they’re fully supported,” he explains.

Those national partners include the Warrior-Scholar Project, a free academic boot camp for veterans interested in pursuing higher education, and the Service to School nonprofit, which provides free application assistance to service members and veterans. In the OMVA’s four-year tenure at Notre Dame, the office has also created professional development events, Military 101 training for faculty and staff and Veteran Preview Weekends.

The OMVA’s newest effort is RouteND, a program that leverages Notre Dame’s wide network of active duty alumni. Through the program, active duty alumni can become RouteND ambassadors and help Notre Dame identify and mentor qualified enlisted service members interested in pursuing a college degree at a top academic institution.

Jones says, “The reason we want more military-connected students on campus, and veteran students specifically, is that they bring leadership, they bring real-world experience and maturity. Student veterans promote diversity of thought and open exchange of ideas in the classroom, which enriches the academic environment on campus for all students.”

For those already enrolled, Jones also wants to ensure they’re adequately supported. Veterans, he notes, have nontraditional needs for university students. They might be married and have kids, or have financial instability or be first-generation college students. Jones hopes his office can serve as an advocate and resource, regardless of the need.

Hentig notes that Jones is the perfect person for the job. As a veteran himself, Jones understands the needs of these students better than anyone, he says, and goes above and beyond to support the students.

“Regan has developed a really good rapport with the veterans that are here,” Hentig says. “He uniquely understands the military-to-civilian transition, and has continued his service out of uniform by ensuring that veterans at ND have all the support they need. All the veterans I know have nothing but great things to say about him and the support that he provides.”

As graduation approaches, Hentig remains committed to helping service members and veterans with traumatic brain injuries. He will be a postdoctoral fellow at the National Institutes of Health focused on the advancement of biomarkers to address TBI and blast injuries in service members and veterans. He hopes to then become an independent senior principal investigator at the NIH or within the Department of Defense.

Reflecting on his work and his drive to learn more, Hentig traces his commitment back to his platoon members, both the ones who were hurt and the ones who made the ultimate sacrifice.

“Unfortunately, there are several individuals that did not come back, and I feel obligated to do the most and the best that I can because they don’t have that opportunity,” he says.