Fighting to combat the opioid crisis

“My son was 25 years old when he died of fentanyl poisoning,” says Jennifer Breaux. “My son didn’t know that what he was given was fentanyl, and he died instantly.

“I miss hearing his laughter. I miss hearing the stories about the fish that he caught. I miss seeing him play with his brothers,” she says, tears streaming down her face. “It’s important to share emotion. It’s real. It’s authentic. It’s what we go through as parents . . . it’s real life.”

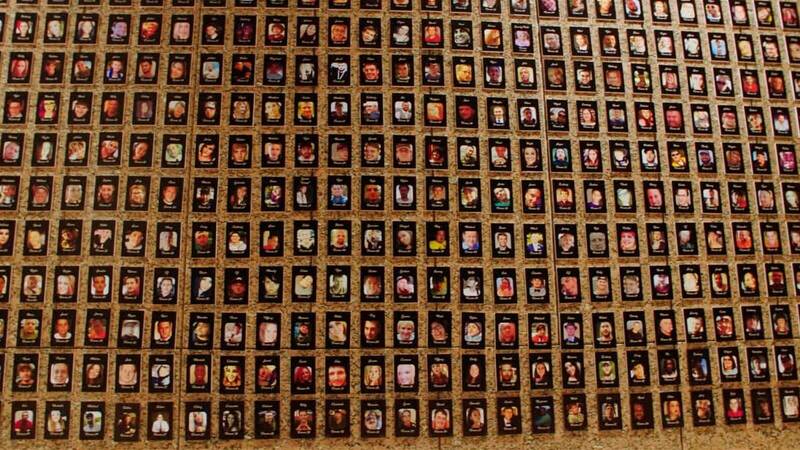

Breaux is not alone. Fentanyl overdoses are now the leading cause of death for people between the ages of 18 and 45. In 2021, the CDC attributed more than 71,000 overdose deaths to synthetic opioids including fentanyl. That number is nearly 23 times the 2013 rate.

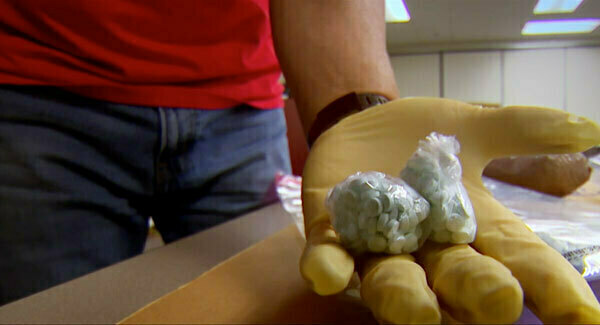

In many cases, fentanyl is being used as filler in other drugs, says Ray Donovan, now the retired chief of operations for the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA). Many people don’t even know that’s what they’re taking.

Donovan first got a glimpse of the power of fentanyl in 2006. He was a special agent in the DEA and busted a fentanyl lab in Toluca, Mexico, that had been responsible for the deaths of 1,000 people in Chicago.

“It’s at least 50 times stronger than heroin. But we’ve seen fentanyl that is one thousand times stronger,” he says.

In 2013, Donovan says, the DEA started seeing the precursor chemicals to make fentanyl smuggled into the United States. By 2015, the DEA put out an alert to law enforcement, because the agency suspected it was being mixed with heroin, cocaine, and methamphetamine. Then fentanyl was pressed into pills, often made to look like well-known prescription medicine.

Now it’s available on social media, Donovan says. Once there were just dark alley handoffs, then illegal drugs appeared on the dark net, and now sellers use apps such as Instagram, Facebook, and Snapchat to sell and deliver them right to your door. The prevalence and ease of obtaining fentanyl, he says, is alarming.

“You have delivery services that are fully operational on these social media platforms that will bring drugs to your location, unbeknownst to you and to parents all across America. These kids that are on TikTok, that are on Snapchat and Instagram and Facebook, that’s where they set up, and they’re selling these drugs as if they’re candy, or as if they’re harmless. There’s all these different colors. They’ll put it in candy boxes, and these kids are being exposed to a highly lethal illicit narcotic.”

Donovan does quick napkin math to estimate that while a kilo of cocaine might yield $250,000 profit, a kilo of fentanyl, which is inexpensive and easy to make, can bring in up to $8 million. With that profit, the cartels, like most companies, are investing in social media, in artificial intelligence (AI), in blockchains, in cryptocurrency, all to secure their long, prosperous futures, he says.

“Criminal groups that have a limitless supply of money and drugs could utilize technology to the extreme, whereas your government agencies are limited to what they can spend money on and how they do it. We don’t have the same limitless supply of cash to go and tackle the big problems.”

That’s where Fanny Ye stepped in. Ye is a collegiate associate professor of computer science and engineering and the associate director of applied analytics in the Lucy Family Institute for Data and Society. Her research focuses on AI, machine learning, data mining, cybersecurity, and public health, all of which she is applying to dismantle online opioid trafficking. Ye started exploring this issue in 2016 while a professor in West Virginia, the epicenter of the opioid epidemic. Since then, she has collaborated with law enforcement, psychiatrists, dietitians, and other computer scientists to understand the problem from all angles. Her work, including another project on opioid resiliency, has garnered attention and is being funded by groups including the National Science Foundation and the Department of Justice.

“Social media platforms and dark net markets have become a direct-to-consumer marketing medium for illicit drug trafficking. One of our goals is to develop AI technologies and data-driven models to fight online opioid trafficking,” Ye says.

She explains that part of her method is to look across all forms of media to find similarities in accounts and posts in order to link and identify traffickers on their many platforms, both illicit and mainstream.

Ye says, “We actually harness large-scale data from both dark net markets and social media platforms. We would like to develop AI models to enable the automatic analysis of this data to detect potential opioid traffickers, and then also link dark net traffickers to the surface web.” This, she says, can expose the potential trafficking rings and help law enforcement with timely leads to combat the deadly industry.

Ye explains that her unique system relies on “signatures” from traffickers—like styles of writing or photography—that AI can trace from platform to platform. By untangling the web of who is who, her team works to dismantle the system that brings these drugs into homes.

Donovan believes this is imperative: “The technology helps from a law enforcement perspective, because the better we become at identifying patterns of criminality, the better we become at pursuing these networks and then holding them accountable,” he explains. “If Fanny’s work is able to bring out those patterns, and so it makes us a lot more efficient, and we can get in front of the problem and not work from behind a problem.”

Technology like Ye’s is but one way the Department of Justice, including the DEA, is ramping up its strategy. Just a few weeks ago, Attorney General Merrick Garland announced a “whole-of-government effort” to tackle the opioid crisis. It included indictments against a host of people and entities involved in producing and distributing fentanyl, sanctions from the Treasury Department, and $345 million in grants for education, prevention, and treatment. The DEA will continue to hunt and seize fentanyl—last year it seized 287 million deadly doses—and it will continue to support Red Ribbon Week, the largest and longest-running prevention campaign, along with take-back events and sites all over the country.

But perhaps the easiest thing, and yet the most important thing to do, says Breaux, is talk about the dangers of drugs.

“It’s uncomfortable, but we need to talk about it until it’s no longer uncomfortable. Have those difficult conversations with your children. Have them with your loved ones. Have them with each other. That’s the only way we are going to stop this madness and stop the deaths.”

She says, “When you bring a child into the world, you never expect them to leave in this way. And I refuse to let this be his legacy. And I will continue to fight. I will continue to fight until my last day, until my last breath, to protect the lives of others.”

As will Ye. Her work to fight the opioid epidemic doesn’t end here. She is now working on a second project advancing AI-driven innovations to promote resilience for teenagers and young adults in preventing opioid misuse and dependence.