Annie Hamilton is a junior at Notre Dame. She studies Chinese and sociology, laughs with her roommates in Ryan Hall, dreams about attending law school, and works out, albeit in a bionic suit. She occasionally needs a hand—like when her wheelchair gets stuck in a snowdrift or when a professor lectures quickly and she needs help with note taking, but here at Notre Dame, she says resolutely, she feels seen as a person, not as a patient.

“Coming to college was very scary for me, but I knew that Notre Dame was the right choice for me because of the community that I felt here on campus,” Hamilton said. “When I visited, everybody was super nice to me and held doors open and were really helpful to me.”

Annie Hamilton es estudiante de tercer año en Notre Dame. Ella estudia mandarín y sociología, se ríe con sus compañeras de habitación en Ryan Hall, sueña con asistir a la facultad de derecho y hace ejercicio, aunque con un traje biónico. A veces necesita una mano, como cuando su silla de ruedas se queda atascada en una pila de nieve o cuando un profesor dicta clase rápido y necesita ayuda para tomar apuntes, pero aquí en Notre Dame, dice con firmeza, se siente vista como una persona, no como una paciente.

“Venir a la universidad me dio mucho miedo, pero sabía que Notre Dame era la opción correcta para mí, debido a la sensación de comunidad que sentía aquí en el campus”, dijo Hamilton. “Cuando visité la universidad, todos fueron muy amables conmigo, me abrieron las puertas y me ayudaron mucho”.

Living with Friedreich's Ataxia

At age 9, Hamilton was diagnosed with Friedreich’s ataxia, a rare disease that impacts around 15,000 people. As her father, Tom, recalls, she was a clumsier child, and it was only after rounds of occupational therapy and physical therapy that a therapist suggested the issue was perhaps neurological. That suggestion led them toward an eventual diagnosis.

Tom explained, “The disease progresses at a relatively slow pace, but it’s just a little bit every day. It starts with clumsiness and bad gait, and eventually you end up in a wheelchair, have a hypertrophic heart, some scoliosis, slurred speech, and everything slowly deteriorates.”

Even with a diagnosis, there wasn’t a clear path forward—because the disease is so rare, there are few experts and little momentum to rally toward research or a cure.

“The doctors unfortunately at the time had very little resources to give us. We were more or less given a pamphlet and told, good luck,” Tom recalled.

Luck wouldn’t be enough for the Hamilton family. Tom quit his job in finance so the family could focus on finding a cure for Friedreich’s ataxia. They set up a family foundation, started biotech companies, sought out clinical trials, and joined boards of national organizations. They modified equipment meant for similar neurological conditions to assist Annie as her symptoms shifted. Quickly, the family became experts in Friedreich’s ataxia.

They aren’t alone. Families across the country are wrestling with similar diagnoses. In the United States, a disease must impact fewer than 200,000 people to be labeled as rare, but there are some 10,000 known rare diseases. That leaves the chances of being diagnosed in the US at 1 in 10, or around 30 million Americans.

Vivir con ataxia de Friedreich

A los 9 años, a Hamilton le diagnosticaron ataxia de Friedreich, una enfermedad rara que afecta a unas 15.000 personas. Como recuerda su padre, Tom, ella era una niña torpe, y solo después de varias rondas de terapia ocupacional y física un terapeuta sugirió que el problema quizás era neurológico. Esa sugerencia los condujo a un eventual diagnóstico.

Tom explicó: “La enfermedad progresa a un ritmo relativamente lento, pero es un poco cada día. “Empieza con torpeza y problemas en la marcha, y al final acabas en silla de ruedas, con hipertrofia cardíaca, algo de escoliosis, dificultad para hablar y todo se va deteriorando poco a poco”.

Incluso teniendo un diagnóstico, no había un camino claro a seguir: debido a que la enfermedad es tan rara, hay pocos expertos y poco impulso para avanzar hacia la investigación o una cura.

“Los médicos en ese momento lamentablemente tenían muy pocos recursos para ofrecernos. Más o menos, nos dieron un folleto y nos dijeron: buena suerte”, recordó Tom.

La suerte no sería suficiente para la familia Hamilton. Tom dejó su trabajo en el sector financiero para que la familia pudiera centrarse en encontrar una cura para la ataxia de Friedreich. Crearon una fundación familiar, iniciaron empresas de biotecnología, buscaron ensayos clínicos y se unieron a juntas directivas de organizaciones a nivel nacional. Modificaron equipos diseñados para condiciones neurológicas similares para ayudar a Annie a medida que sus síntomas progresaban. Rápidamente, la familia se convirtió en experta en la ataxia de Friedreich.

Ellos no están solos. Familias de todo el país están luchando con diagnósticos similares. En Estados Unidos, una enfermedad debe afectar a menos de 200.000 personas para ser etiquetada como rara, pero hay unas 10.000 enfermedades raras conocidas. Esto deja las posibilidades de ser diagnosticado en los EE. UU. en 1 de cada 10, o alrededor de 30 millones de estadounidenses.

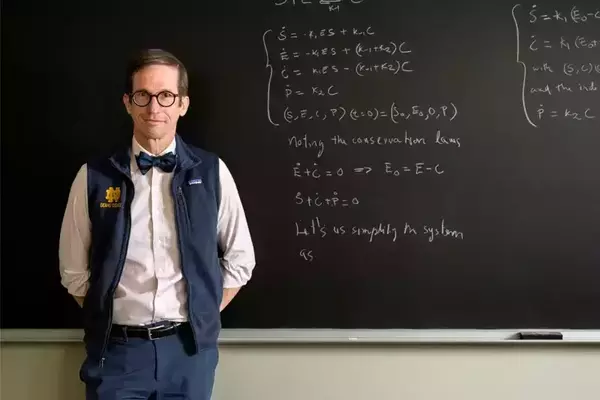

Notre Dame’s commitment to rare disease research

Santiago Schnell, the William K. Warren Foundation Dean of the College of Science, explained, “What happens with rare diseases is that they’re called orphan diseases. And the reason is because the federal government and the pharmaceutical industry don’t see them as a priority. And they’re not a priority because the number of individuals that suffer from a particular rare disease is very small. As a result, effective treatments exist for fewer than 5 percent of all rare diseases, leaving hundreds of millions worldwide without options.”

At Notre Dame’s Boler-Parseghian Center for Rare Diseases, faculty are undaunted by the so-called small numbers. They study everything from patient data to tissue samples, molecular targets, and diagnostic and treatment efforts. Notre Dame was one of the first academic institutions in the country to establish a basic science rare disease research center.

Schnell emphasized the immense importance and opportunity in researching rare diseases: “Studying a single rare disease not only advances our understanding and treatment of that specific condition, but also unlocks valuable insights with broad implications for countless other diseases. For instance, research funded by the Ara Parseghian Medical Research Fund at Notre Dame on Niemann-Pick Type C (NPC)—a terminal neurodegenerative disease primarily affecting children—has deepened our knowledge of other cholesterol storage-related diseases and neurological conditions like Alzheimer’s. Additionally, recent findings suggest that mutations associated with NPC might even prevent Ebola virus infection.

It is a missed opportunity for academic institutions and the biomedical research community not invested in rare diseases as they hold the key to uncovering fundamental secrets of health that can transform medicine for a wide range of conditions.

Santiago Schnell

William K. Warren Foundation Dean of the College of Science

Patient-centered research

To do that well, Notre Dame factors another distinctive aspect into its research: It places patients and families at the center of its work. While Notre Dame researchers had not studied Friedreich’s ataxia before Annie’s matriculation, when she arrived, the College of Science asked how it could help. In addition to students providing help with everything from taking notes to brushing teeth, the college was also prepared to throw some academic weight behind the issue. Ultimately, Zach Schafer, a biologist with expertise in cancer cells, and Rebecca Wingert, a biologist who studies kidney development, offered to consider how their work might apply to Friedreich’s ataxia. Students in their labs jumped on board as well.

El compromiso de Notre Dame con la investigación de enfermedades raras

Santiago Schnell, Decano de la Facultad de Ciencias de la Fundación William K. Warren explicó: “Lo que pasa con las enfermedades raras es que se las llama enfermedades huérfanas. Y la razón es que el gobierno federal y la industria farmacéutica no las ven como una prioridad. Y no son una prioridad porque el número de personas que padecen una determinada enfermedad rara es muy pequeño. Como resultado, existen tratamientos efectivos para menos del 5 por ciento de todas las enfermedades raras, lo que deja a cientos de millones de personas en todo el mundo sin opciones”.

En el Centro Boler-Parseghian de Enfermedades Raras de Notre Dame, los docentes no se dejan intimidar por estos números reducidos. Estudian todo, desde datos de pacientes hasta muestras de tejido, objetivos moleculares y procesos de diagnóstico y tratamiento. Notre Dame fue una de las primeras instituciones académicas del país en establecer un centro de ciencias básicas para la investigación de enfermedades raras.

Schnell destacó la inmensa importancia y oportunidad que supone la investigación sobre enfermedades raras: “Estudiar una sola enfermedad rara no solo mejora nuestra comprensión y tratamiento de esa afección específica, sino que también revela conocimientos valiosos con amplias implicaciones para innumerables otras enfermedades. Por ejemplo, la investigación financiada por el Fondo de Investigación Médica Ara Parseghian de Notre Dame sobre la enfermedad de Niemann-Pick tipo C (NPC), una enfermedad neurodegenerativa terminal que afecta principalmente a los niños, ha profundizado nuestro conocimiento sobre otras enfermedades relacionadas con el almacenamiento de colesterol y enfermedades neurológicas como el Alzheimer. Además, hallazgos recientes sugieren que las mutaciones asociadas con el NPC podrían incluso prevenir la infección por el virus del Ébola.

Es una oportunidad perdida para las instituciones académicas y la comunidad de investigación biomédica que no invierten en las enfermedades raras, ya que estas tienen la clave para descubrir secretos fundamentales de la salud que pueden transformar la medicina para una amplia gama de condiciones.

Santiago Schnell

Decano de la Facultad de Ciencias de la Fundación William K. Warren

Investigación centrada en el paciente

Para lograrlo, Notre Dame tiene en cuenta otro aspecto distintivo en su investigación: Sitúa a los pacientes y a las familias en el centro de su trabajo. Aunque los investigadores de Notre Dame no habían estudiado la ataxia de Friedreich antes de la admisión de Annie, cuando ella llegó, la Facultad de Ciencias preguntó cómo podría ayudarle. Además de brindar ayuda a los estudiantes con todo, desde tomar apuntes hasta cepillarse los dientes, la universidad también estaba preparada para respaldar la cuestión con cierto peso académico. Al final, Zach Schafer, un biólogo con experiencia en células cancerosas y Rebecca Wingert, una bióloga que estudia el desarrollo del riñón, se ofrecieron a investigar sobre las posibles aplicaciones de su trabajo a la ataxia de Friedreich. Los estudiantes en sus laboratorios también se sumaron al proyecto.

Tom Hamilton said, “Notre Dame’s work in rare disease is really different than most schools. They definitely fight above their weight, and they coordinate and bring researchers together from around the globe to fight and push for many rare diseases in the community.

“At Notre Dame, rare disease research is right on mission. How are we going to make the world a better place? How are we going to coordinate selflessly to cure these disorders for people that can’t help themselves?” he added.

The research does link inextricably to Notre Dame’s mission, though perhaps in this case it’s the uncommon good. What’s more, for Schnell, a mathematical biologist, the issue is personal. Schnell’s mother and sister lost repeated pregnancies and children, only to discover they were carriers of a rare condition called Haddad syndrome. When Schnell was a Wellcome Trust Senior Research Fellow at Oxford, one of his nephews was hospitalized and his sister called to implore him: Use your gifts to study rare diseases.

Tom Hamilton dijo: “El trabajo de Notre Dame en materia de enfermedades raras es realmente diferente al de la mayoría de las facultades. Definitivamente luchan por encima de sus posibilidades y coordinan y reúnen a investigadores de todo el mundo para apoyar y concientizar sobre muchas enfermedades raras en la comunidad.

“En Notre Dame, la investigación sobre enfermedades raras va por buen camino. ¿Cómo vamos a hacer del mundo un lugar mejor? ¿Cómo vamos a coordinarnos de forma desinteresada para curar estos trastornos a personas que no pueden ayudarse a sí mismas?, añadió.

La investigación está inextricablemente vinculada a la misión de Notre Dame, aunque quizás en este caso se busca el bien poco común. Más aún, para Schnell, un biólogo matemático, la cuestión es personal. La madre y la hermana de Schnell perdieron repetidos embarazos e hijos, sólo para descubrir que eran portadoras de una rara enfermedad denominda síndrome de Haddad. Cuando Schnell era investigador principal del Wellcome Trust en Oxford, uno de sus sobrinos fue hospitalizado, y su hermana lo llamó para implorarle: Utiliza tus dones para estudiar enfermedades raras.

Looking ahead

It made a lasting impact on him. Throughout his career, he has published extensively on numerous rare diseases, demonstrating his unwavering commitment to this critical area of research. Since joining Notre Dame, he has intensified the College of Science’s focus on rare diseases, overseeing the launch of the nation’s first minor in rare disease patient advocacy. He has also expanded engagement with the rare diseases community. He holds a deep commitment, both personal and professional, for families like the Hamiltons—people facing seemingly insurmountable challenges yet determined to make something good from it, all while caring for a loved one.

“The Hamilton family is truly extraordinary. Few families possess the strength and determination not only to seek a cure for their own child, but also to champion the cause of others suffering from rare diseases. Their commitment transcends self-preservation; they are dedicated to advancing medical discoveries that will allow others to lead healthier lives. Their advocacy requires immense courage and bravery, qualities that are rare and admirable,” Schnell said. “The Hamilton family’s dedication to this cause is an inspiration, and there are few who could undertake such a noble and altruistic endeavor.”

It isn’t easy, Tom said. He recalled that soon after Annie’s diagnosis, he zeroed in on the potential for severe heart issues. He felt it was a pressing need to start there. But it was Annie who nudged him to redirect course based on her own lived experience of losing mobility.

“I think as a parent you think you know best the needs of your child, and my wife, Karen, and I pushed to try to provide everything we could for Annie,” he said. “The reality is Annie knows what she needs and has really given us direction as to what kind of support she needs, what kind of medicines that would be important. She often said to us once, ‘I’d rather have a short sweet life than a long miserable one.’ And she knows best and she has guided our family through that process.”

Mirando hacia el futuro

Esto tuvo un impacto indeleble en él. A lo largo de su carrera, ha realizado extensas publicaciones sobre numerosas enfermedades raras, lo que demuestra su compromiso inquebrantable con esta área crítica de investigación. Desde que se unió a Notre Dame, ha intensificado el enfoque de la Facultad de Ciencias en enfermedades raras, supervisando el lanzamiento de la primera especialización en defensa de pacientes con enfermedades raras del país. También ha ampliado la participación en la comunidad de enfermedades raras. Ha asumido un profundo compromiso, tanto personal como profesional, con familias como los Hamilton: personas que enfrentan desafíos aparentemente insuperables pero que están decididas a sacar algo bueno de estos, todo ello mientras cuidan a un ser querido.

“La familia Hamilton es verdaderamente extraordinaria. Pocas familias poseen la fuerza y la determinación, no sólo para buscar una cura para sus propios hijos, sino también para defender la causa de otras personas que padecen enfermedades raras. Su compromiso trasciende la autoconservación; están dedicadas a promover descubrimientos médicos que permitan a otras personas llevar vidas más saludables. “Su trabajo de incidencia requiere un inmenso coraje y valentía, cualidades que son difíciles de encontrar y admirables”, dijo Schnell. “La dedicación de la familia Hamilton a esta causa es una inspiración, y hay pocos que podrían asumir un esfuerzo tan noble y altruista”.

No es fácil, dijo Tom. Recordó que poco después del diagnóstico de Annie, se concentró en la posibilidad de que presentara problemas cardíacos graves. Sintió que era una necesidad urgente empezar por ahí. Pero fue Annie quien lo empujó a reorientar el rumbo basándose en su propia experiencia de pérdida de movilidad.

“Creo que, como padre, crees que conoces mejor las necesidades de tu hijo, y mi esposa, Karen, y yo nos esforzamos para tratar de darle todo lo que pudimos a Annie”, dijo. “La realidad es que Annie sabe lo que necesita y realmente nos ha orientado sobre qué tipo de apoyo necesita y qué clase de medicamentos serían importantes. Ella nos decía a menudo: "Prefiero tener una vida corta y dulce que una vida larga y miserable". Y ella lo sabe mejor que nadie y ha guiado a nuestra familia a través de ese proceso”.

Annie Hamilton is a junior at Notre Dame who enjoys hanging out with friends, attending class, and living in Ryan Hall.

Now at Notre Dame, Annie offers that perspective to students in the College of Science’s Patient Advocacy Initiative and the minor in science and patient advocacy. Students in the program are offered training to help them to better advocate for the rare disease community, whether they go on to medical school or into advocacy roles.

“I chose to be a patient advocate because I think that it’s very important for doctors and researchers to hear from the patients, because a lot of times they don’t really get to see the actual patients,” Annie said. “I think that it’s very important to share my experiences with them and everybody that I can in order to try and help push along research.”

Annie is also a member of the Access-ABLE student club and Notre Dame’s Accessibility Leadership Fellows program, where she mentors younger students with disabilities, especially as they transition to college. And, her father notes, her impact goes far beyond campus.

“Annie also has given her support back to the community. She’s an ambassador for the Friedreich’s Ataxia Research Alliance. She’s spoken at different biotech companies about her experience as a patient, and I think she feels an obligation to not just have it be about her, but to help the entire rare disease community.”

Annie added, “The advice that I would give to anybody suffering from a rare disease about going to college is to step outside of your comfort zone and do things that scare you. I know for me, coming to college was very scary and I did not want to go at all. But I knew that I had to come in order to grow as a person and help myself as well as others.”

“I knew that going away to college would be difficult, but when I visited Notre Dame, I knew that it would be the perfect place. I feel seen here.”

Annie Hamilton

Now, she’s staring down her future undaunted. She’s considering law school, the FBI, leveraging her Chinese degree to do business overseas. Her future-facing attitude has trickled down to her dad, too. He now looks at not just a cure for Annie, not just a cure for Friedreich’s ataxia, but for a number of other neurological conditions, too.

“Our ultimate goal for the future is finding a cure for Friedreich’s ataxia,” he said. “And hopefully the findings from that will domino into other diseases like MS and Parkinson’s and other rare disorders.”

Together, they’re fighting not just for Annie, but for so many with rare diseases.

Ahora en Notre Dame, Annie ofrece esa perspectiva a los estudiantes de la Iniciativa de defensa del paciente de la Facultad de Ciencias y la especialización en ciencias y defensa del paciente. A los estudiantes del programa se les brinda capacitación para ayudarlos a abogar mejor por la comunidad de enfermedades raras, ya sea que vayan a estudiar medicina o a asumir roles de incidencia.

“Elegí ser defensora de los pacientes porque creo que es muy importante que los médicos y los investigadores escuchen a los pacientes, porque muchas veces no llegan a verlos realmente”, dijo Annie. “Creo que es muy importante compartir mis experiencias con ellos y con todas las personas que sea posible, para intentar ayudar a impulsar la investigación”.

Annie también es miembro del club de estudiantes Access-ABLE y del programa de Becarios de Liderazgo en Accesibilidad de Notre Dame, donde asesora a estudiantes más jóvenes con discapacidades, especialmente en su transición a la universidad. Y su padre señala que su impacto se extiende mucho más allá del campus.

“Annie también ha devuelto su apoyo a la comunidad. Ella es embajadora de la Alianza para la investigación de la ataxia de Friedreich. Ha hablado en diferentes empresas de biotecnología sobre su experiencia como paciente, y creo que siente la obligación de no solo hablar de ella, sino de ayudar a toda la comunidad de enfermedades raras”.

Annie agregó: “El consejo que le daría a cualquier persona que sufra una enfermedad rara y quiera ir a la universidad es que salga de su zona de confort y haga cosas que le den miedo. Sé que para mí, venir a la universidad fue muy aterrador, y no quería hacerlo en absoluto. Pero sabía que tenía que venir para crecer como persona y ayudarme a mí misma y a los demás”.

“ Sabía que ir a la universidad sería difícil, pero cuando visité Notre Dame, supe que sería el lugar perfecto. “Me siento reconocida aquí.”

Annie Hamilton

Ahora, ella mira hacia el futuro sin temor. Está considerando estudiar derecho, ingresar al FBI y aprovechar sus conocimientos de mandarín para hacer negocios en el extranjero. Su actitud de mirar hacia el futuro también ha influido en su padre. Ahora no sólo busca una cura para Annie, no sólo una cura para la ataxia de Friedreich, sino también para una serie de otras enfermedades neurológicas.

"Nuestro objetivo final para el futuro es encontrar una cura para la ataxia de Friedreich", afirmó. “Y esperamos que los resultados obtenidos tengan un efecto dominó sobre otras enfermedades como la esclerosis múltiple, el mal de párkinson y otras condiciones raras”.

Juntos, luchan no sólo por Annie, sino por muchas otras personas que padecen enfermedades raras.

Credits

- Writer: Tara Hunt McMullen

- Photographers: Matt Cashore and Barbara Johnston

Créditos

- Escritora: Tara Hunt McMullen

- Fotógrafos: Matt Cashore and Barbara Johnston