Fighting for the Lives of Children

When your child is diagnosed with a rare, genetic disease, it feels like you’re rolling down a mountain, just waiting to hit rock bottom, says Doug Berns. When his daughter, Samantha, was diagnosed with Niemann-Pick Type C, an incurable, neurodegenerative disorder, he and his wife watched as Samantha’s energy depleted, her balance became shaky, and her laughter quieted.

While looking for support groups, Berns stumbled upon the Ara Parseghian Medical Research Foundation website. They were hosting a rare disease day at Notre Dame the following week. The Berns family got in their car and drove to meet families, researchers and clinicians who also knew the telling signs of the devastating disease.

There they met Dr. Elizabeth Berry-Kravis ’79, a pediatric neurologist at Rush University Medical Center. Though her research had been focused on Fragile X syndrome and other developmental disorders, a family had approached her about treating Niemann-Pick. Then another. With the demand, she began a multi-patient, compassionate use protocol on a new drug for treating Niemann-Pick Type C. This process, also referred to as expanded access, occurs when a patient is not formally enrolled in a clinical trial but still chooses to receive the treatment. The Berns family asked if Samantha, too, could be enrolled. Berry-Kravis said yes.

“That day,” Berns says, “changed our entire lives.” For the first time since Samantha’s diagnosis they had hope.

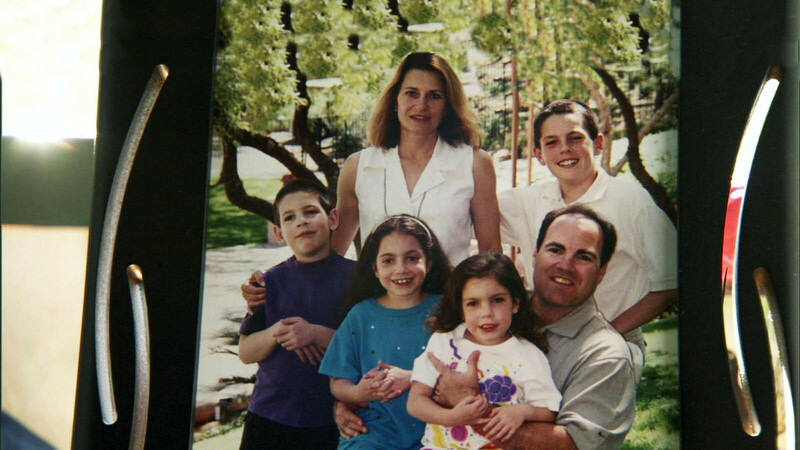

Mike and Cindy Parseghian are too familiar with the heartache which stems from a Niemann-Pick Type C diagnosis. Three of their four children, Michael, Christa and Marcia, succumbed to the disease. In the wake of the horrifying diagnoses, the two 1977 graduates rallied together, along with Mike’s father, Notre Dame football coach Ara Parseghian, and created the Ara Parseghian Medical Research Foundation, a non-profit organization which funds medical research to find treatments for Niemann-Pick Type C and related disorders, and which merged with Notre Dame in 2016 to create the Ara Parseghian Medical Research Fund.

In 1997, a team funded by the APMRF discovered the cause of Niemann-Pick Type C. The disease occurs from a mutation in either the NPC1 or NPC2 genes which produce proteins that move lipids within cells. If these lipids are not moved to the correct location, cells cannot properly function and eventually the cells die, resulting in tissue and organ damage. Symptoms also include poor muscle tone, motor incoordination, liver and lung disease, difficulty swallowing and seizures.

Since the discovery, more than 200 projects at 75 labs across the globe have been funded by APMRF, including several at Notre Dame’s Boler-Parseghian Center for Rare and Neglected Diseases. Researchers in this group seek to identify and advance treatments for a number of rare diseases. To date, the U.S. recognizes 7,000 rare diseases which are defined by an incidence of less than 200,000 nationally.

As the Parseghians sought researchers to tackle NPC, they approached Paul Helquist, a chemist at Notre Dame whose research was primarily in basic scientific research, but who had begun dabbling in drug compounds for rare diseases.

“I'll never forget that day back in September of 2004, a date that really changed the focus of what I would be doing for the next several years,” Helquist says. “I remember Cindy Parseghian, in particular, looked me straight in the eye and said, ‘Paul, can you help us?’ It was at that moment that I felt I had a tremendous opportunity to use my skills to solve a problem I would never have conceived of pursuing previously.”

More than a decade later, he’s still at work, along with a large, national group of researchers in academic labs and at the National Institutes of Health. Helquist’s greatest contribution is the design and preparation of new, potential drugs as improvements of existing therapies.

He explains, “What we do is take suggestions from people in the broad Niemann-Pick community, in terms of what might be a lead for developing a new therapeutic, then we take it from there to actually develop new compounds that could be the next drugs for treating the disease.”

Helquist is joined by a number of others at Notre Dame, too. While Helquist is a synthetic chemist by training, his faculty colleague, Professor Olaf Wiest, uses computer technology to understand how drugs work and can be improved.

“[Wiest’s] expertise is using computer technology to actually understand how drug molecules work and how to design them to be better,” Helquist says. “He uses very sophisticated computer technology to design the next generation of drugs, then he says, ‘Paul, go make them.’”

Others at Notre Dame, including Kasturi Haldar and Rich Taylor, have also contributed to the NPC cause, as has Notre Dame’s Warren Family Research Center for Drug Discovery and Development and the Boler-Parseghian Center for Rare and Neglected Diseases.

“Many of the diseases we have today will be treated genetically rather than with traditional medicine. Even at this early stage, there's a lot of promising results on that front for treating Niemann Pick.”

— Paul Helquist

For years, APMRF has funded investigations for therapeutics for this disease. In March, a preparation of cyclodextrin compounds called VTS-270 made it to full enrollment of a phase 2b/3 clinical trial with more than 50 enrolled participants. The trial is being run based on cooperative research and development agreement between the NIH and Sucampo Pharmaceuticals, Inc., who acquired Vtesse and VTS-270 in April. Initial results from an earlier phase 1/2b trial look promising and introduce the possibility that a drug could halt or reverse some of the symptoms associated with Niemann-Pick. Helquist will now take this drug and others and tweak them to see if he can make them more effective.

“The basic problem with it now is insufficient penetration of the brain. The treatment does not reach all the critical regions of the brain. What we’re working on at Notre Dame is how do you solve that problem?” Helquist says.

Even with such promising treatment, Helquist is also looking ahead to a cure, which he believes will be genetics based. At the annual APMRF meetings, Helquist says the genetics teams devoted to NPC have shared their impressive work, and he’s optimistic for the future of genetic treatment.

“So many of the diseases we have today will be treated genetically rather than with traditional medicine. Even at this early stage, there’s a lot of promising results on that front for treating Niemann Pick. It’s not quite there yet, but it’s come along remarkably fast.”

As a pediatric neurologist, Dr. Elizabeth Berry-Kravis is the one who sits with a family and shares a heartbreaking diagnosis. In the case of rare diseases like Niemann-Pick, she also must break the news there is no cure. But with the new cyclodextrin trials, Berry-Kravis can now share something a little more uplifting: hope.

“When you think back, 25 years ago we didn't even know what the gene was. We didn't even know what the problem was in NPC,” she says. Now, there are nearly 84 patients receiving treatment through the clinical trial or expanded access protocol for the cyclodextrin drug.

Berry-Kravis’ involvement began when a family pleaded that she begin expanded access protocol. Once she did, more and more patients asked to be involved. Soon, her name got to the company hosting the clinical trial and they requested she help design it and become a co-investigator.

“My work has kind of gone from just seeing a few patients to an explosion of patients because we had this compassionate use protocol,” she says. “People who couldn't qualify for the trial could join at any time. Eventually, we got to the point where we were looking at doing 30 LP infusions every two weeks, which is a lot…We worked with the F.D.A. to create a scenario where we would have multiple sites.”

Those sites don’t just administer an injection. They monitor progress or regression of a number of neurological domains. Berry-Kravis says it’s crucial to understand not just whether the treatment works, but for how long, on what symptoms and areas of brain function, and whether it has consistent results in all patients. That data will take time to accumulate, but there’s optimism across the board.

When the Parseghian family began their foundation in 1994, the goal was to save the lives of their children. Sadly, Michael passed in 1997 at age 9, followed by Christa in 2001 at age 10, and Marcia in 2005 at age 16.

Ara also passed this August at age 94. Though he didn’t see the realization of a cure for NPC, Helquist contends he was a driving force in the fight against the disease. Mike Parseghian agrees, and adds there are many willing to continue to carry the torch.

“Dad gave his heart and soul to the Ara Parseghian Medical Research Foundation. But the foundation still has a heart and soul. The heart and soul is Dad's legacy, the inspiration of our three children, Michael, Marcia and Christa. It's the scientific advisory board and the scientists that continue to work. It's the hundreds of volunteers who've worked for the foundation over the past two decades,” Mike Parseghian says. “And I think most importantly, it's the families that have Niemann-Pick Type C children whose hopes and dreams are with the foundation in developing a cure.”