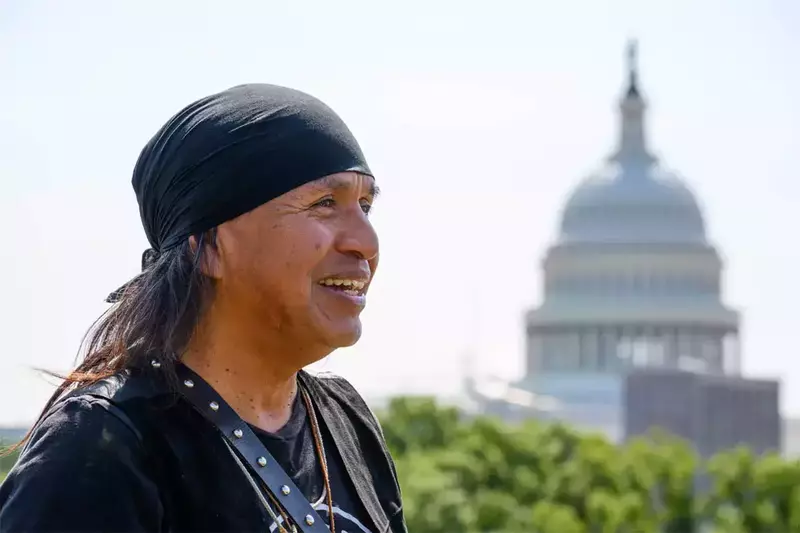

Wendsler Nosie Sr., a San Carlos Apache tribe member, stands overlooking Chi’chil Biłdagoteel, known as Oak Flat, in Arizona’s Tonto National Forest.

He explains that Oak Flat is a sacred space for the Apache and other Native peoples. The Apache believe Oak Flat was touched by their creator, and it is where the angels and their Ga’an people reside; it is a corridor between Heaven and Earth, where they can commune with the sacred.

Oak Flat is lifegiving, says Nosie. A mountaintop in this high desert landscape gathers snow, which flows into tributaries and into deep water. It sustains life, from plants to animals to humans. The Apache collect water and medicinal plants here. They collect food and honor their ancestors.

This land is undeniably irreplaceable. And yet, Oak Flat is in danger.

In 2014, in a midnight rider on a defense funding bill, a land swap deal offered Oak Flat to the international mining company Rio Tinto. The company intended the land for a Resolution Copper mine, which would take copper ore from 7,000 feet underground and leave Oak Flat as a crater 2 miles wide and 1,000 feet deep. In essence, the land would be destroyed completely and unsafe for humans.

Apache Stronghold, a 501(c)(3) nonprofit community organization made up of Native and non-Native allies intent on saving Oak Flat, has fought the decision. The group argued the deal violated a historic lien on the land from an 1852 Treaty of Santa Fe. They argued it violated a protection under federal law that had held since the 1950s. And they argued it infringed on their religious freedom. That’s where Notre Dame’s Lindsay and Matt Moroun Religious Liberty Clinic comes in.

Wendsler Nosie Sr., miembro de la tribu Apache de San Carlos, mira hacia Chi'chil Biłdagoteel, conocido como Oak Flat, en el Bosque Nacional Tonto de Arizona.

Él explica que Oak Flat es un espacio sagrado para los apaches y otros pueblos nativos. Los apaches creen que Oak Flat fue tocado por su creador y que es donde residen los ángeles y su pueblo Ga'an; es un corredor entre el Cielo y la Tierra, donde pueden comunicarse con lo sagrado.

Prácticas como la ceremonia de mayoría de edad de una mujer apache, que se ve aquí, se verán alteradas o terminarán para siempre con la destrucción de Oak Flat.

Oak Flat es dador de vida, dice Nosie. En la cima de una montaña en este paisaje de alto desierto se acumula nieve, que fluye hacia afluentes y aguas profundas. Sostiene la vida, desde las plantas hasta los animales y los humanos. Los apaches recogen aquí agua y plantas medicinales. Recolectan alimentos y honran a sus antepasados.

Esta tierra es indudablemente irremplazable. Y, sin embargo, Oak Flat está en peligro.

En 2014, en un acuerdo de intercambio de tierras sobre un proyecto de ley de financiación de la defensa, se ofreció Oak Flat a la compañía minera internacional Rio Tinto. La compañía destinó el terreno a la mina Resolution Copper, que extraería mineral de cobre de 7.000 pies bajo tierra y dejaría Oak Flat como un cráter de 2 millas de ancho y 1.000 pies de profundidad. En esencia, la tierra quedaría destruida por completo y no sería segura para los humanos.

Apache Stronghold, una organización comunitaria sin fines de lucro bajo el artículo 501(c)(3), formada por aliados nativos y no nativos que desean salvar Oak Flat, ha luchado contra la decisión. El grupo argumentó que el acuerdo violaba un gravamen histórico sobre la tierra de un Tratado de Santa Fe de 1852. Argumentaron que esto violaba una protección bajo la ley federal vigente desde la década de 1950. Y argumentaron que esto violaba su libertad religiosa. Ahí es donde la Clínica de Libertad Religiosa Lindsay y Matt Moroun entra en juego.

Religious liberty, a fundamental human right

Informed by its Catholic character, Notre Dame has always supported and promoted religious liberty as a fundamental human right. And in 2020, Notre Dame Law School launched the Religious Liberty Clinic, now one of the world’s leading academic institutions on the subject of religious freedom.

The clinic serves as a teaching law practice that not only contributes scholarship and research in this field, but also actively defends and counsels those needing help in the field of religious liberty.

Marcus Cole, the Joseph A. Matson Dean and Professor of Law at Notre Dame Law School, is careful to note that religious liberty encompasses all faiths, and those without faith.

La libertad religiosa, un derecho humano fundamental

Inspirada en su carácter católico, Notre Dame siempre ha apoyado y promovido la libertad religiosa como un derecho humano fundamental. Y en 2020, la Facultad de Derecho de Notre Dame inauguró la Clínica de Libertad Religiosa, ahora una de las instituciones académicas líderes a nivel mundial en el tema de la libertad religiosa.

La clínica funciona como un consultorio jurídico de enseñanza que no sólo contribuye con conocimientos e investigaciones en este campo, sino que también defiende y asesora activamente a quienes necesitan ayuda en el campo de la libertad religiosa.

Marcus Cole, decano Joseph A. Matson y profesor de Derecho en la Facultad de Derecho de Notre Dame, es cuidadoso al señalar que la libertad religiosa abarca todas las fés, incluso aquellas que no tienen religión.

“The Religious Liberty Clinic was created because our freedom of conscience, our freedom to believe, and then live according to our beliefs, is the most important and fundamental freedom that we have. Not just as Americans, but as humans,” he said.

“All other rights are founded upon freedom of conscience. Freedom of speech means nothing, freedom of the press means nothing if you can’t believe what you have to say or what you have to print. And so my hope for the Religious Liberty Clinic is that it’ll be a living testament to Notre Dame’s commitment to freedom of conscience for all people. And it will be a testament to Notre Dame’s commitment to human flourishing.”

The clinic’s case roster is vast and includes work in a variety of contexts representing individuals and organizations from a diversity of faith traditions.

“La Clínica de Libertad Religiosa se creó porque nuestra libertad de conciencia, nuestra libertad de creencia y el poder vivir de acuerdo con nuestras creencias, es la libertad más importante y fundamental que tenemos. No sólo como estadounidenses, sino como seres humanos”, afirmó.

“Todos los demás derechos se fundamentan en la libertad de conciencia. La libertad de expresión no significa nada, la libertad de prensa no significa nada si no puedes creer lo que tienes que decir o lo que tienes que publicar. Así que mi esperanza para la Clínica de Libertad Religiosa es que sea un testimonio viviente del compromiso de Notre Dame con la libertad de conciencia para todas las personas. “Y será un testimonio del compromiso de Notre Dame con la prosperidad humana”.

La lista de casos de la clínica es amplia e incluye trabajos en una variedad de contextos que representan a individuos y organizaciones de una diversidad de tradiciones religiosas.

“Religious freedom is universal. It doesn’t apply only if you believe certain things or belong to a certain tradition,” said John Meiser, associate clinical professor and director of the Religious Liberty Clinic. “The work of our clinic reflects that. With our students, we serve all who are in need and offer aid to anyone who might be suffering from the denial of this most foundational right.”

Most recently, the clinic successfully led the federal appeal of a volunteer prison minister who had been excluded from visiting a jail in Georgia because of his religious beliefs. The clinic currently represents a group of Catholic educators hoping to expand educational opportunities in Oklahoma in an appeal to the US Supreme Court. Outside the courtroom, the clinic advises religious organizations in transactional matters and has represented several individuals seeking refuge from religious persecution in their home countries—including helping win asylum for a young Uyghur Muslim earlier this year.

The clinic has also filed dozens of amicus curiae (or “friend of the court”) briefs to advocate for religious freedom in an array of contexts. The clinic’s briefs have represented Christian, Jewish, Muslim, Native American, and Sikh groups to advocate for religious exercise in prison, the freedom to operate a religious food ministry to feed the hungry, the preservation of Native sacred rituals, and much more.

Figure 1: In 2014, a parcel of land, including Oak Flat, was released by the federal government to Resolution Copper, a mining company, in exchange for other land the company owned elsewhere in Arizona. The Oak Flat site is a federally protected area listed on the National Register of Historic Places, and its destruction may also be in violation of the Religious Freedom Restoration Act.

Since its earliest days, the clinic has filed a series of amicus briefs—first in the district of Arizona, then the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, and now the United States Supreme Court—in support of protection for Oak Flat along with other Indigenous sacred sites around the country.

Olivia Lyons, a law student and one of the first recipients of the Murphy Fellowship for students exploring law and religion, said, “Religious liberty law hasn’t developed to accommodate land-based religions the same way it’s developed to accommodate other religions.”

Lyons explained: “Religious liberty law initially developed mostly with regards to religions that have churches. So you think about Christianity typically, at least in the United States, we own the land that our churches are on, but that’s not the case for Native Americans. A lot of them don’t own the land that houses their most sacred spaces, which creates a lot of legal issues for them. And religious liberty law doesn’t really accommodate those issues, but it needs to in order to vindicate their rights.”

Lyons has hands-on experience in this field. As a law student, she worked on two different cases advocating for two different Native American tribes, as well as cases representing Jewish students and a Catholic organization. She said that variety and that openness to all cases is a hallmark of how the Religious Liberty Clinic functions.

“I think that the Constitution is a constitution for all peoples, and here at the Law School, we believe that. And if we were only taking cases that particularly aligned with our faith tradition, I don’t think that that would reflect the spirit of religious freedom. And I think it’s important for people to recognize that this fight isn’t just for Christians or for Jews or for Muslims or whatever faith. It’s for people of all faith, including people of Native American faiths who are often left unrecognized.”

After graduation, Lyons intends to clerk in Columbia, South Carolina, for the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals, and then for the Western District of Kentucky in Louisville.

“La libertad religiosa es universal. “No se aplica sólo si crees en ciertas cosas o perteneces a una determinada tradición”, declaró John Meiser, profesor clínico asociado y director de la Clínica de Libertad Religiosa. “El trabajo de nuestra clínica refleja eso. Con nuestros estudiantes, servimos a todos los que lo necesitan y ofrecemos ayuda a cualquiera que pueda estar sufriendo la negación de este derecho tan fundamental”.

Más recientemente, la clínica dirigió con éxito la apelación federal de un ministro voluntario de prisiones a quien se le había impedido visitar una cárcel en Georgia debido a sus creencias religiosas. La clínica actualmente representa a un grupo de educadores católicos que esperan ampliar las oportunidades educativas en Oklahoma en una apelación ante la Corte Suprema de los Estados Unidos. Fuera de los tribunales, la clínica asesora a organizaciones religiosas en cuestiones transaccionales y ha representado a varias personas que buscan refugio de la persecución religiosa en sus países de origen, incluida la ayuda para obtener asilo para un joven musulmán uigur a principios de este año.

La clínica también ha presentado docenas de escritos amicus curiae (o “amigos de la corte”) para defender la libertad religiosa en una variedad de contextos. Los escritos de la clínica han representado a grupos cristianos, judíos, musulmanes, nativos americanos y sikh para defender el ejercicio religioso en prisión, la libertad de operar un ministerio de alimentación religiosa, de alimentar a los hambrientos, la preservación de los rituales sagrados indígenas, y mucho más.

Figura 1: En 2014, el gobierno federal entregó una parcela de tierra, incluida Oak Flat, a Resolution Copper, una empresa minera, a cambio de otras tierras que la empresa poseía en otras partes de Arizona. El sitio de Oak Flat es un área protegida a nivel federal incluida en el Registro Nacional de Lugares Históricos, y su destrucción también podría violar la Ley de Restauración de la Libertad Religiosa.

Desde sus inicios, la clínica ha presentado una serie de escritos amicus curiae (primero en el distrito de Arizona, luego en el Tribunal de Apelaciones del Noveno Circuito y ahora en la Corte Suprema de los Estados Unidos) en apoyo de la protección de Oak Flat junto con otros sitios sagrados indígenas en todo el país.

Olivia Lyons, estudiante de derecho y una de las primeras beneficiarias de la Beca Murphy para estudiantes que exploran el derecho y la religión, sostuvo: “La ley de libertad religiosa no se ha desarrollado para dar cabida a las religiones basadas en el territorio de la misma manera que se ha desarrollado para dar cabida a otras religiones”.

Lyons explicó: “La ley de libertad religiosa inicialmente se desarrolló principalmente con respecto a las religiones que tienen iglesias. Así que, en general, si pensamos en el cristianismo, al menos en Estados Unidos, somos dueños de la tierra donde están nuestras iglesias, pero ese no es el caso de los nativos americanos. Muchos de ellos no son propietarios de los terrenos que albergan sus espacios más sagrados, lo que les genera muchos problemas legales. Y la ley de libertad religiosa realmente no contempla esas cuestiones, pero debería hacerlo para reivindicar sus derechos”.

Lyons tiene experiencia práctica en este campo. Como estudiante de derecho, trabajó en dos casos diferentes defendiendo a dos tribus nativas americanas diferentes, así como en casos representando a estudiantes judíos y a una organización católica. Dijo que la variedad y la apertura a todos los casos es un sello distintivo de cómo funciona la Clínica de Libertad Religiosa.

Olivia Lyons es una estudiante de derecho de tercer año y becaria Murphy en la Facultad de Derecho de Notre Dame.

“Creo que la Constitución es una constitución para todos los pueblos y aquí en la Facultad de Derecho sostenemos esa creencia. Y si sólo tomáramos casos que se alinearan particularmente con nuestra tradición religiosa, no creo que eso reflejaría el espíritu de la libertad religiosa. Y creo que es importante que la gente reconozca que esta lucha no es sólo para cristianos, o judíos, o musulmanes, o cualquier otra fe. “Es para personas de todas las religiones, incluidas las personas de religiones nativas americanas que a menudo no son reconocidas”.

Después de graduarse, Lyons tiene la intención de trabajar como secretaria en Columbia, Carolina del Sur, para el Tribunal de Apelaciones del Cuarto Circuito, y luego para el Distrito Oeste de Kentucky en Louisville.

An appeal to the US Supreme Court

As it pertains to Oak Flat, Notre Dame’s Religious Liberty Clinic does not represent Nosie or Apache Stronghold. They are represented by Becket Law, a national law firm that specializes in defense of religious liberty. But Notre Dame's clinic has filed five amicus curiae briefs at varying levels in support of the case. The latest amicus brief was filed on October 15 to the US Supreme Court.

Amicus briefs provide a court with valuable context on the wider impact or history of an existing case. Meiser, the clinic’s director, explained that in this case, the clinic filed briefs on behalf of a coalition of individuals and organizations who support tribal rights and who work to preserve Indigenous spiritual practices and cultural heritage. The clinic’s briefs highlighted the potentially devastating impact beyond the parties in the case, including the grave consequences the threatened destruction would have for all Native Americans. They also urged the court to ensure federal law is interpreted to provide Indigenous religious and spiritual practices with the same robust protections afforded to more mainstream religious practices and to situate the case within the long history of the government’s abuse of Native Americans.

The Law School’s involvement is powerful, Nosie said. “When I think about the work, even just the name Notre Dame, it carries a really big impact that tells everybody else that if Notre Dame can listen, why can’t we listen?”

Un recurso ante la Corte Suprema de Estados Unidos

En lo que respecta a Oak Flat, la Clínica de Libertad Religiosa de Notre Dame no representa a Nosie ni a Apache Stronghold. Están representados por Becket Law, una firma de abogados nacional especializada en la defensa de la libertad religiosa. Pero la clínica de Notre Dame ha presentado cinco escritos amicus curiae en distintos niveles en apoyo del caso. El último escrito amicus fue presentado el 15 de octubre ante la Corte Suprema de Estados Unidos.

Los escritos de amicus curiae brindan al tribunal un contexto valioso sobre el impacto más amplio o la historia de un caso en curso. Meiser, director de la clínica, explicó que en este caso, la clínica presentó escritos en nombre de una coalición de personas y organizaciones que apoyan los derechos tribales y que trabajan para preservar las prácticas espirituales y el patrimonio cultural indígenas. Los informes de la clínica destacaron el impacto potencialmente devastador más allá de las partes en el caso, incluidas las graves consecuencias que la destrucción en ciernes tendría para todos los nativos americanos. También instaron al tribunal a garantizar que la ley federal se interprete para brindar a las prácticas religiosas y espirituales indígenas las mismas protecciones sólidas que se otorgan a las prácticas religiosas más convencionales y a situar el caso dentro de la larga historia de abuso del gobierno a los nativos americanos.

La participación de la Facultad de Derecho es poderosa, dijo Nosie. “Cuando pienso en este trabajo, incluso solo el nombre Notre Dame, tiene un impacto realmente grande que le dice a todos los demás que si Notre Dame puede escuchar, ¿por qué nosotros no podemos hacerlo?”

And listening has been Nosie’s goal for some time. This summer, he and a caravan of other Apache Stronghold members undertook a cross-country prayer journey en route to file their case with the Supreme Court. They started in Seattle with the Lummi Nation before making their way southwest to speak with other peoples including the Hopi, Diné, and Cherokee. The group spoke with crowds in Los Angeles, Phoenix, Raleigh, Philadelphia, and Montgomery, Alabama, where they visited the sites of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s home and the church where he was a full-time pastor.

In a written statement, Nosie said, “We need to come together on this court case, our spirituality and the survival of the earth are at stake, the suffering of the people is what we are bringing to the Supreme Court.”

Now the US Supreme Court will consider whether to review the case. That decision could impact a multitude of other sacred Indigenous sites.

Nosie is skeptical. It’s not the first time Native land has been a place of contention. He tells tales of his family’s connection to Geronimo, a famous historical Apache leader; of being imprisoned on the San Carlos reservation; of shifting narratives between Native Americans and the federal government; of the runover of other sacred places like those belonging to the East Coast tribes, the Midwest tribes, the Northern tribes. He speaks of the wake of devastation each one leaves and of the future of his tribe—how his people want to defend the Southwest, the Earth, their way of being.

“It’s not only about fighting for Oak Flat, but it’s fighting about sustainability for the future,” Nosie said. “In our religious way, we’re here to protect God’s greatest gift.”

And Notre Dame’s Religious Liberty Clinic is here to support them in that fight. Dean Cole said, “Our clinic took on this case because we think it’s important to stand up for all people who are people of belief or no belief at all—and to demonstrate that they have the right to live according to their beliefs.”

Y escuchar ha sido el objetivo de Nosie durante algún tiempo. Este verano, él y una caravana de otros miembros de Apache Stronghold emprendieron un viaje de oración a través del país con miras a presentar su caso ante la Corte Suprema. Comenzaron en Seattle con la Nación Lummi antes de dirigirse al suroeste para hablar con otros pueblos, incluidos los Hopi, los Diné y los Cherokee. El grupo habló con multitudes en Los Ángeles, Phoenix, Raleigh, Filadelfia y Montgomery, Alabama, donde visitaron los sitios de la casa del Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. y la iglesia donde era pastor a tiempo completo.

En una declaración escrita, Nosie dijo: “Necesitamos unirnos en este caso judicial, nuestra espiritualidad y la supervivencia de la tierra están en juego, el sufrimiento de la gente es lo que estamos llevando ante la Corte Suprema”.

Ahora, la Corte Suprema de Estados Unidos considerará si revisará el caso. Esa decisión podría afectar a muchos otros sitios sagrados indígenas.

Nosie es escéptico. No es la primera vez que los territorios indígenas han sido motivo de discordia. Cuenta historias de la conexión de su familia con Gerónimo, un famoso líder histórico apache; de su encarcelamiento en la reserva de San Carlos; de las narrativas cambiantes entre los nativos americanos y el gobierno federal; de la invasión de otros lugares sagrados como los que pertenecen a las tribus de la Costa Este, las tribus del Medio Oeste y las tribus del Norte. Habla de la estela de devastación que cada uno deja y del futuro de su tribu, de cómo su gente quiere defender el Suroeste, la Tierra, su forma de ser.

"No se trata sólo de luchar por Oak Flat, sino de luchar por la sostenibilidad hacia el futuro", dijo Nosie. “Estamos aquí para proteger el mayor regalo de Dios, a la manera de nuestra fe”.

Y la Clínica de Libertad Religiosa de Notre Dame está aquí para apoyarlos en esa lucha. Dean Cole dijo: “Nuestra clínica se hizo cargo de este caso porque creemos que es importante defender a todas las personas, sean creyentes o no creyentes en absoluto, y demostrar que tienen derecho a vivir de acuerdo con sus creencias”.

Credits

Writer: Tara Hunt McMullen

Photographer: Matt Cashore

Créditos

Escritor: Tara Hunt McMullen

Fotos: Matt Cashore