Read the transcript

The transcript has been formatted and lightly edited for clarity and readability.

Introduction:

Welcome to Notre Dame Stories, the official podcast of the University of Notre Dame, where we push the boundaries of discovery, embracing the unknown for a deeper understanding of our world.

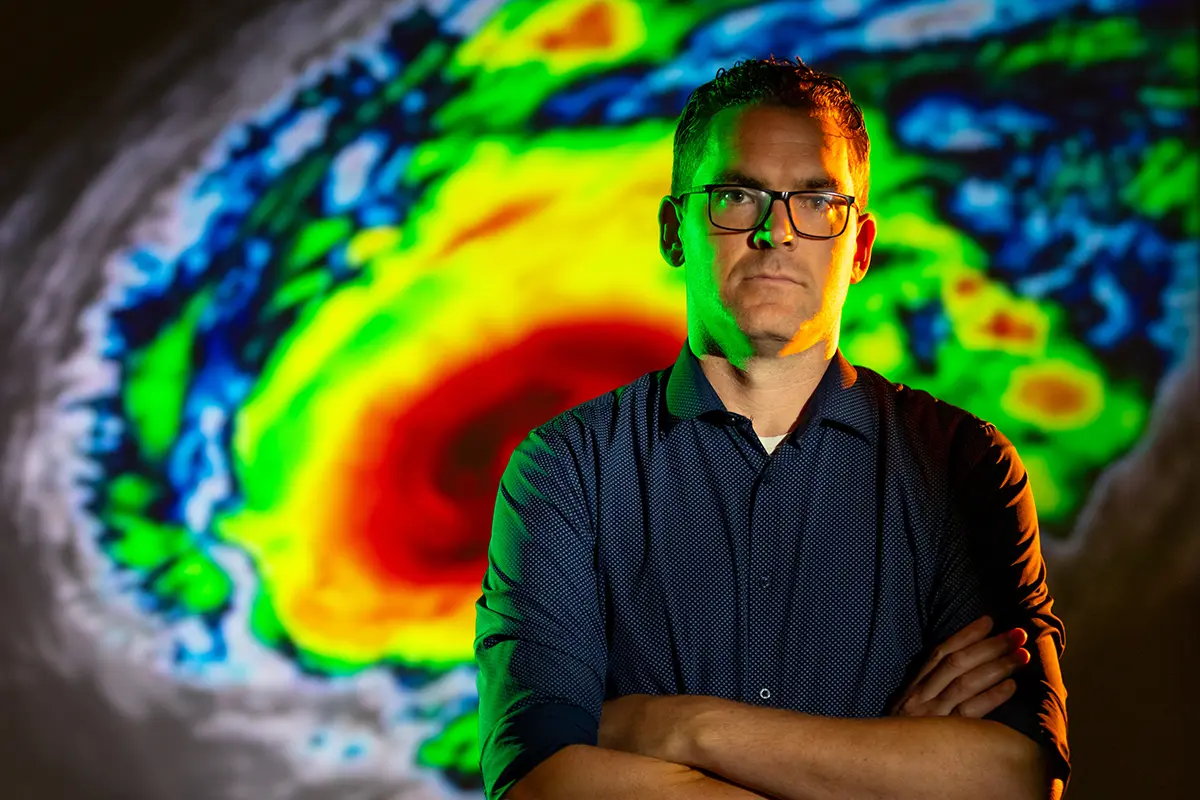

Today's guest is Professor David Richter. He's the Frank M. Freimann Collegiate Professor of Environmental Fluid Dynamics. We're talking to him about some of the most powerful storms on Earth and what we still need to learn about them.

Jenna Liberto:

You study hurricanes specifically, right? Tell me about your work.

David Richter, the Frank M. Freimann Collegiate Professor of Environmental Fluid Dynamics, Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering and Earth Sciences:

I'm not a meteorologist, right? I'm not a trained meteorologist; my degrees are all mechanical engineering. What I like to focus on, broadly, at least in the engineering world, is the area of fluid mechanics. You know, anything that kind of moves continuously. So the ocean, you know, then you have things like storms and tornadoes, and hurricanes are just kind of a fluid mechanical event, and that's the part where I get really excited.

There are a lot of really skilled people at NOAA and elsewhere who are doing forecasts. They're looking at models. They're using their intuition. They're looking at, you know, satellite imagery, and they're trying to understand where these are going to be and then warn people of the impacts. I'm really trying to understand, you know, how these things work.

Jenna Liberto:

What don't we still know, in 2025, about hurricanes that you're trying to understand better to get at?

David Richter:

Yeah. So, forecasts, right? So where is the storm going to be at a certain time out in the future, and how strong is it going to be when it gets there? And there's lots of different ways that this can go awry. You can predict the strength or the intensity of the storm. Well, let's say that you do, but you get the location wrong, right? You think it's going to be here, but it's actually 200 miles south.

Well, if you warned, and people evacuated in the north and not in the south, even though you got part of the answer right, you know ... a lot of problems. I mean, a lot of people's lives might be damaged. You might lose lives, and people should have evacuated and they didn't—but I would say a more kind of behind-the-scenes, or indirect, problem is that then people lose faith in the forecast.

So the next time around, are people going to believe it? "Oh, well, they were off by 200 miles." But, you know, a general trend is that we've gotten better and better and better at forecasting the hurricane tracks, but to get the intensity right, you really have to zoom in on what's going on at what we call the air-sea interface, or kind of where the atmosphere hits the ocean.

Because, generally speaking, we know how that works, but the details are really, really complicated, right? You have 40-foot waves and they're breaking, and so you've got spray droplets all around. It's raining. Yeah, there's just a lot of unknowns still. Even basic questions about, you know, what controls some of these things.

Jenna Liberto:

And I'm guessing to really understand, you can't just watch a hurricane from the outside and get the kind of information that you want to get to learn more. So what are you doing differently?

David Richter:

Yeah, that is absolutely part of the equation, right? You know, one of the major breakthroughs in being able to predict these things is the advent of satellites. And one thing that they notably can't really see well is right down at the surface. What you would like to be able to do is just kind of take a boat or somehow get into the bottom 100 feet of the atmosphere inside of these intense regions. But you can't. It's really unsafe.

One of the key pieces that I'm working with is, we're trying to send these kinds of remote-controlled aircraft, these aerial drones, but we're trying to make measurements in a place where, yeah ... it's nearly impossible to make them any other way.

Jenna Liberto:

And you have one of these, you have one of the drones?

David Richter:

Yes, I have a model of it sitting in my office.

Jenna Liberto:

Let's go get it. And then I have more questions. In here?

David Richter:

I don't think we can go this way.

Jenna Liberto:

Oh, "Alarm will sound."

David Richter:

Yes.

Jenna Liberto:

I'll follow you since this is your space.

David Richter:

So, this is actually a poster that we have on the project. Ah, OK. The idea is that, you know, here's this little aerial drone. Here's a side cut of a hurricane, and we're trying to get down here. There's going to be stuff floating on the ocean surface, and then we want to fly these drones like right above it.

This is it all bundled up. I did not develop this. There's a whole team at NOAA called the Emerging Technologies Team, and their charge is to, you know, what are the technologies that we need in order to make the measurements in the regions where we have not been able to ever before? And so the idea is that we're using this technology that is still just coming online.

The way that this is deployed, right—so this is, you know, somewhat heavy. And you've got these arrows right here. So, how this is deployed is that NOAA flies P-3 aircraft into every storm bait. Any storm that's anywhere near the United States or any US territory, including, like, St. Croix and Puerto Rico. You know, NOAA and Air Force will actually fly what they call the Hurricane Hunters, and they'll go crisscross back and forth across the hurricane.

I mean, they're flying through the hurricane at maybe 10,000 feet. And, along the way, they're making all sorts of measurements. They have radars attached to the airplane. They dropped these things called dropsondes. They're just little cardboard tubes which measure things as they fall down to the surface. And then what they did was they designed this tube so that it could be launched out of the same thing. So on the aircraft, on the P-3 aircraft, they take this tube, and they just shove it out the bottom of the aircraft and, then, in the air, this thing pops out.

[I'm] probably gonna have to release this. In the air, this process happens automatically, right?

So then this detaches. This falls off the wings—spreads out. The antenna pops up. And then it's hanging by a parachute, you know, kind of upside down like this at some point, and then this drops out as well. And then you've got this thing flying around. You can hold it if you'd like.

Jenna Liberto:

Yeah, it's very light.

David Richter:

Yes. And so it can power itself, but you know, it's 3 pounds. Its max speed is about 20 meters per second. But the wind speeds in these storms are 90 meters per second [201 mph]. So it gets whipped around quite a bit, but it can maintain a pretty level altitude, which is pretty remarkable. And again, I had nothing to do with the design of this. It was a company that's based in Boulder, Colorado, with some aerospace engineers in coordination with the Emerging Technologies group.

Jenna Liberto:

Is this physical thing that I'm holding taking in readings?

David Richter:

That's right. On the front here, you've got little holes which are measuring pressure, and from the pressure you can actually back out what the wind speed is. And they're oriented in different ways so you know what the different wind components are. It's got something that's pointing downwards. They can actually measure how far away the ocean surface is.

On the back, you have temperature and humidity sensors. It's measuring pressure as well. And so, yeah, that's kind of all on board, and then it transmits it back to the airplane from which it was launched. And they're, you know, they collect the data in real time. And so, it flies around. The idea is to fly it around for close to two hours.

Jenna Liberto:

What do your methods tell us that traditional methods used up until this time just haven't been able to?

David Richter:

Yeah. So the thing I'm interested in is what we'd call turbulence. If you fly in a commercial aircraft and you bounce up and down, it's kind of these chaotic motions, but those are the motions which are, actually, doing a lot of the transfer of, again, the heat and the moisture and the momentum. That's what's going on at the ocean surface that we want to know.

And so, what we're measuring and analyzing in a way that hasn't been done are those motions down near the surface, right? We want to fly this thing as close to the ocean surface as we can get and measure these turbulence properties and statistics that really—I mean, we don't have any direct measurements of these. They just simply don't exist.

Jenna Liberto:

David, this is cool. This is just cool stuff. This is fascinating work. But beyond that for you, what beyond it's just cool? What drives this work for you personally?

David Richter:

For me personally. So, you know, I really want to study something that can actually help people, to be able to predict these things. How strong are [these storms] going to be and where are they going to be? Where and when are they actually going to hit? You know, if you can get that right and confidence is built that these things are reliable, a lot of good can be done. A lot of good can be done. You know, for both human lives as well as property and, you know, families, and that's a really cool feeling. And again, it's a very small component.

I, still to this day, am just fascinated by the math and the physics of it. There's just something jaw-dropping, in my opinion, about just trying to understand creation a little bit more. I think of it in terms of understanding God's creation better and better and better. And for me, I would say, that's a huge drive of what I do and why. Because we're just kind of gifted with this creation that's all around us. And the same laws of physics that make it possible to enjoy a sunset are also the same laws of physics that create storms, which can cause all sorts of destruction.

And the more we can understand, again, there's one aspect, like I just said, of like trying to, you know, help human lives, but the other is just, let's just try to get a better understanding about what's going on here. Again, in these regions of the storm we just, really, don't have a clue what's going on. I mean, we have a general idea, but we've never been there in this kind of way. And that, to me, of just learning something new about creation, is just really, really fantastic.

Jenna Liberto:

And that's really at the intersection of faith and science, which is a place that Notre Dame exists in so beautifully. And I know you do, too. You teach a class on faith and science.

David Richter:

Right. So every student at Notre Dame has to take two philosophy and two theology courses. And somewhere in 2017, they started something where someone outside of philosophy can offer a course. If it meets certain criteria, it could count as a student's second philosophy. So I offered one from the College of Engineering called Engineering and the Human Vocation, and it was really just, "What does it even mean to be an engineer?"

Like, an engineering degree and an engineering profession, is that something that you're actually called to do? And, you know, if the answer is yes, then it's, “Well, who's calling, and how do you even hear it and respond to it?” If not, then, you know, is there anything that you're being called to? Is this, you know, is it a means to an end? "Oh, I'm called to religious or family life and, you know, my engineering career is just simply a way for me to earn a paycheck." And, I think, there's legitimate arguments for one versus the other.

And so, we read and try to ... I force them to try to answer that question, basically. But then we get into, you know, what makes a good engineer? You know, you can be skilled at what you're doing. You could be excellent at differential equations or designing robots, and all the sorts of things that they do in here, but you could do terrible things with them. And, you know, there's no shortage in history of that. I mean, I talk about that in class. Clearly, being a good engineer means more than just getting A's in classes and having a technical proficiency. And so, you could just call it ethics, but I try to challenge them to go a little bit deeper, and that's when I get into like, look, you know, whereas science might be more of like, "All right, we want to discover things about the natural world around us," engineers are manipulating that same thing, right? They're doing things with it. But I try to emphasize that.

I mean, this stuff exists without any of your input, right? Like it is a gift to you, and I try to ask them to approach their entire lives—but, certainly, their profession—in terms of a certain humility. The hurricane is going to be there, and I would love to understand it. It is not something that you get to control outside of yourself. I try to get them to zoom back and then start asking questions about, like, make sure that you understand where you are in the broader sense of creation, because you're actually a really small component of it.

And once you understand that and can really move with that, that's when you have the freedom to start being a really, truly excellent engineer. It makes you relate to other people differently. It helps you understand who you're serving and why. And I think that's really important. And that's something that Notre Dame has this just fantastic opportunity to emphasize. You know, for a student here to hear about the fluid mechanics of hurricanes, and then go to a philosophy course and then go to a theology course, and actually have those sorts of conversations—"Why do bad things happen to good people?"—is just a tremendous opportunity.