Read the transcript

The transcript has been formatted and lightly edited for clarity and readability.

Introduction:

18 million adults in the United States have no high school diploma. In many states, there’s an age limit to receive one. Goodwill started the first Excel Center, an adult high school, and is working to change state policies to make more centers available nationwide. Notre Dame has shown these schools provide not only an education but a substantially more promising future. What would you fight for? Fighting to improve education policies. We are the Fighting Irish.

Jenna Liberto:

That was Fighting to improve education policies, just one way we’re committed to the broader issue of poverty. Notre Dame is fighting to end poverty through coordinated efforts all over campus, but what does it mean to fight poverty using research? We start that conversation with Heather Reynolds, managing director of the Notre Dame Poverty Initiative and the Michael L. Smith Managing Director of the Wilson Sheehan Lab for Economic Opportunities (LEO).

Welcome to Notre Dame Stories, the official podcast of the University of Notre Dame. Here we take you along the journey where curiosity becomes a breakthrough for people using knowledge as a means for good in the world.

Heather, thank you so much for joining me. It’s great to be here, thank you. I’ve been really looking forward to talking with you and I want to know a little bit more about your background. I know that you haven’t been in higher education your entire career, but your commitment to poverty started far sooner than when you joined the Notre Dame campus. So just tell me about your Notre Dame story.

Heather Reynolds:

Yeah. Well, thank you for having me. It’s a joy to be with you this morning. My story with Notre Dame . . . I’m not an alum. I’ve not been in higher education—never thought I would be in higher ed. My story, actually, started because I am a social worker by training. I spent almost two decades at Catholic Charities in Fort Worth Texas, the last 13 as their CEO, and it was through Catholic Charities Fort Worth that I met Notre Dame and began to see the brilliance, paired with the humility, that Notre Dame really offers.

And so, what happened in my case is, I got a call one day from, at the time the CEO of Catholic Charities USA, and he said, “I just met these two economists at the University of Notre Dame and they think they could really help us fighting poverty. Would you come up to South Bend?” And so, I said, “Of course! Sure, why not?” Not really sure what he was talking about. And came up to Notre Dame for the first time, and at that convening was a small group of economists and a small group of Catholic Charities organizations, and it was being led by Jim Sullivan and Bill Evans, two members of the Department of Economics here. And they were talking about this idea that, you know, what Notre Dame has is, you know, a wonderful ability to produce rigorous research—help us answer important questions. And what providers have is all of these programs and services we’re running but where we’re not really sure what’s working and what’s not.

And, oh my gosh, it was like this is like [sings Ahhhhh] what I’ve been looking for. This is what our organization needs. We had a, you know, we were a large organization, we’re a $45 million nonprofit organization serving hundreds of thousands of people a year, but I didnt’ know what was working and what was not working. And so, we at Catholic Charities Fort Worth were like, “Notre Dame, we need you.” And they began running experiments after experiments on our programs, and we began to really learn what was working and what was not. And it changed the face of the way we did business and, really, it changed the face of the way we were really serving and having good results for the poor. And that’s what it’s all about.

And so, that’s how I got to know Notre Dame, and so, fast forward, Jim and Bill start LEO. Jim and Bill several years later realize, you know, “OK, this is getting big, we need somebody to come lead this.” And my family and I made the decision to move to South Bend, Indiana, three weeks before a polar vortex. Coming from Texas—a little confused about what . . . —and join the Notre Dame family.

Jenna Liberto:

As it goes, right?

Heather Reynolds:

Yeah, as it goes. And so, I don’t have a desire to be in higher ed, I have a desire to be at Notre Dame because this place really knows what it means to be a force for good in the world.

Jenna Liberto:

And while, really, from the get-go, you have the perspective of any-sized organization that’s working on something like poverty, you have to be good stewards of your time, of money, certainly. Is that one thing that drew you in from the get-go? Like, this is the missing piece?

Heather Reynolds:

Oh, so much! Because, if you think about, you know, if you think about you and I, let’s go to Starbucks. You know, we are the payer and we are the customer, right, of that. When you look at like the way nonprofits or social services work, the payer and the customer are two different things, so what that results in is, you have like two people you are accountable to: You have the people who are giving you the resources to do the mission and the social good, and you have the actual people who are in pain and crisis and have unreal trauma that you really need to be right for.

You need to do right by those donors but then, also, if somebody’s walking through your doors and says, “I am in pain. I am in poverty. I am struggling.” Like, they deserve to be given a program or a service that actually works and that we know works. Notre Dame can unlock these questions and help us answer these things we need to understand. And we owe it to those who give so generously and we owe it to those who are in such pain from what poverty robs people of. We owe it to them to be giving them programs that work.

Jenna Liberto:

Would you be willing to share your personal motivation for this lifelong commitment you have to reducing poverty? Because that was a leap of faith, it seems like, you took even though, obviously, it has worked quite well here. What was that driving factor for you, personally, to say this is the right step for me, for my family?

Heather Reynolds:

Yeah, yeah. It’s interesting because, in my career, you know, I started off as a social worker. I realized that you need to have a lot more patience to be a good therapist than what God naturally blessed me with. But something really changed in my heart back in 2012, and that was my personal story of my husband and I’s journey to become parents. So our journey to become parents—we became parents through adoption—and we . . . our adoption story led us to Taichung, Taiwan, where we adopted our little girl when she was 10 months old.

And the way adoption worked at the time, there is . . . Olive was born in January, in March we were matched, but then the way the legal proceedings happen, we weren't allowed to go travel to get her till November. And so, we saw the first 10 months of our daughter’s life, you know, through videos, through pictures, through all of that. And when we finally, though, went—happiest day of our life was our family “gotcha day”—and that was the day we met Olive for the first time.

But shortly after, about two hours later, we had the opportunity to meet Olive’s birth family. And included in that was Olive’s birth mother, who was a 16-year-old girl. And she had shared with us that she had learned English from the time she knew she was placing Olive with us till the time we arrived. And the reason she had learned English is because she wanted to be able to tell us, in her own words, what her hopes and dreams were for her daughter, and they were beautiful. She wanted her to learn to read, she wanted her to be loved, and she wanted her to be who she was intended to be.

And I just remember, in that moment—I mean, I was crying, I was smiling. I mean, just there were so many emotions going through me at that moment, but what was such an a-ha to me, in that moment, was this mom and the extended family who were present, they wanted Olive. They loved this little girl. They were showering us with, you know, gifts of gratitude for raising her and being willing to raise her. It was really poverty that kept them from being able to be family—be present family to Olive. And I remember thinking that, in this 16-year-old girl’s poverty, I’m becoming a mother.

And while I’m so thankful that Olive’s, you know, our daughter, and while I love my silly now 13-year-old, it really was a convicting moment to me to realize that I want to use my life in a way that doesn’t just help at the individual change level but also at the systems level because, as long as we have these systems that still don’t solve poverty at its roots, the more moms having to make these choices that they just . . . poverty should not rob a mom of her ability to be a mom, and it does.

And so that really started stirring me in this direction. And so my mind started to turn to systems after that, and I was getting to know Notre Dame at that time and then, you know, made the decision at the end of 2018 to come to Notre Dame in 2019.

Jenna Liberto:

Heather, did that give you a global perspective, too, that you’ve brought into your work here at Notre Dame?

Heather Reynolds:

Yeah. That’s a great question. So, you know, LEO . . . My career has been very domestic-focused. Even at LEO it has been very domestic-focused. Where my mind has started to be able to go broader is the way both my experience with our adoption—experience overseas—but then, also, we were very . . . I’ve been very fortunate to be involved with a Provost Initiative that has stemmed from the strategic framework that has said, you know, this University is not . . . We don’t only care about poverty, we’re prioritizing poverty and poverty research and solving this.

Jenna Liberto:

Right.

Heather Reynolds:

And so, because of my now engagement in that initiative, too, I’ve really gotten to know a lot of the amazing things we’re doing across campus in the global poverty environment. And whether that’s, you know, a biologist who is really zoned in on helping focus on how we find cures to different parasite issues, to what our friends in Keough are doing, to new migration faculty we’re hiring because we want to understand the intersection of migration and poverty. It’s a really exciting time to be at Notre Dame.

Jenna Liberto:

Absolutely. You’ve described LEO’s work as the crossroads of research and real-world impact, so I’d like to talk about one of those examples. Our What would you fight for? piece featuring Patrick Turner speaks to that idea—again, research real/world impact. Can you give us an overview on how LEO has helped shape education policy—and we’re specifically talking about people obtaining a high school degree instead of a GED?

Heather Reynolds:

You know, one of the things that’s important to know about LEO is we have over 100 projects going on in 30 states across the country. Because what we’re trying to do is answer these important questions. And, a lot of times, when people talk about research, it’s kind of like, “Well, what is this? What’s the need for it?” It makes a lot of sense when you think about cancer research, you know, or disease research, but when it comes to poverty, like what does that mean? What is that really all about?

And the way I like to think about it is like, what we care about here is impact. We want to change people’s lives. We want to make sure they are not struggling in poverty. Period. End of story. Research becomes a critical input to figure out how to do just that. And so, when you look at LEO and our impact in the policy space, specifically as it relates to education policy, that’s really what it’s been about.

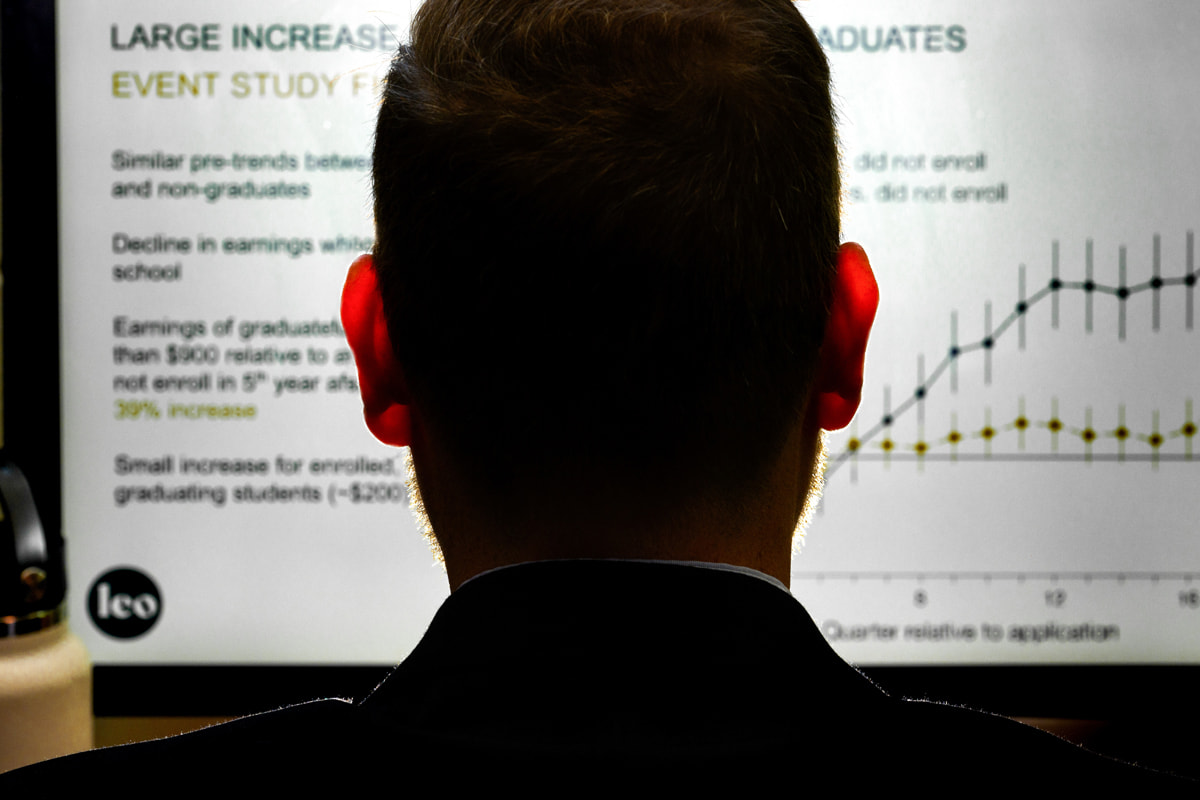

So we meet the Goodwill Excel Center, right, that started in Indianapolis. They say, “We are running this really, we think, cool program that’s helping people earn their high school diploma who are adults, which is typically not very possible. And we are surrounding them with wraparound services. And we’re ensuring them they have some postsecondary training—vocational training—so they can live a life outside of poverty. We don’t know if it works. Will you help us understand if it works?” And we’re like, hot dog, let’s go!

And so, we run a study with them, understand that it works and it works incredibly well, and so, instead of just publishing an article, which is beautiful and great, we also then say, OK. How do we take what we learned here to change the way philanthropy is investing? To change the way policy is working? To change the way services are being provided?

And so, in that very specific example, we were able to change state policy in Arizona where, now, they will allow people over the age of 21 to get a high school diploma, which was not allowed beforehand. We helped get the governor there to sign a proposal that has allocated money to start their first Goodwill Excel Center in Phoenix. The movement just happened to get the next one in Indiana. Huge amounts of resources have been allocated to expand Goodwill Excel Centers. Now Goodwill Excel Centers are in 10 states across the country.

It’s just, you know, that’s the power of Notre Dame building this research—building this evidence. When we know what works, it can cut through “Are you a Democrat?” “Are you a Republican?” It can cut through opinions and, you know, all of this. It takes it to, like, “What does this really tell us?” and then, “How do we all do what’s best for the poor based on what the research says?”

Jenna Liberto:

I was just going to point out that very fact. It’s one thing to influence policy change, another to do that with bipartisan support, and that’s something the University has been able to do.

Heather Reynolds:

Huge. HUGE. I mean, we are so lucky to be at Notre Dame, first of all, because we are such a, I believe, trusted brand to begin with. I think that makes a huge difference for us. But when you look at what LEO has been able to do, you know, one of the things that I think is really important is we were very instrumental in the Evidence-Based Policymaking Act that passed into law in 2019, and that was an effort led by then-Speaker Paul Ryan (Republican) and Senator Patty Murray (Democrat) and, you know, it was a . . . it was, from the start, across the aisles working together to make it where law got put into practice that we want to make sure more and more of the way we’re serving the poor in our country, throughout our nation, has evidence, and that research is a part of that. That we know what works. That the poor deserve that.

And so, yeah, I love that we tend to be a group who’s successful among Republicans and Democrats because we believe in the preferential option for the poor and, then, we speak in fact of what our research tells us.

Jenna Liberto:

Talk about some of the other spaces where this research is happening or, maybe, what other partners you’re engaging in similar work.

Heather Reynolds:

How long do we have?

Jenna Liberto:

Oh, all the time. All the time.

Heather Reynolds:

Yeah, so, one of the things that . . . you know, our focus is on poverty, but I think the thing that’s important to remember about poverty is, it intersects with so many things, like you just said with poverty and education. We’re very active in the criminal justice space. Over 90 percent of those sitting in jails and prisons today will be released. We understand two-thirds go back into prison and jail, and so, like, we need to solve that. That’s a big . . . that’s a big deal.

We’re very involved in the space of foster care and poverty. The people in our country who have the worst outcomes of any other group are those who are in the child welfare system. And so, you think about the trauma a child has when they are victims of abuse and neglect. The next trauma they have often is being raised in the child welfare system. They have so little chance of being successful in adulthood. And so, lines of research in that space is an area we’re focused on.

A lot in homelessness and housing: LEO has really gained a name for ourselves in homeless prevention. That has been a really important area that was understudied until we came on the market. And that, yeah, like, you know, it’s great to help the homeless in our country, but that’s, actually, a very, very small fraction of those struggling in poverty. It’s often what we think about because that’s what we see, right?

But the reality is, there are so many people that are on the . . . just a step away—37 million people are living in poverty and just a step away from being homeless. And so, we begin to turn our attention to, How do we make sure that somebody who is on the brink of homelessness does not falter into homelessness? Because, when you do, your problems get all the more complex. So we have a whole series of projects in that space.

And then, there’s a lot we’re doing in health that ranges from starting a research line on the opioid epidemic and how to really zone in to help there. Anyway, in the space of poverty, there’s so many angles that LEO is working to address.

Jenna Liberto:

Let’s talk more about the opioid crisis because, of course, it is of such great impact in our country. Talk about LEO’s work.

Heather Reynolds:

One of the things . . . I mean, so many people are impacted by the opioid crisis. We have lost more people to this crisis—lives lost—than we’ve lost to military service since the Revolutionary War, just to put this into some perspective. The way Notre Dame is really attacking this issue is that, we know this issue exists, we’ve done a lot of research on the problem itself, but now we really need to pivot to finding solutions with communities across the country.

And so we hosted, in August, a convening among our research community who have expertise in this area. Mostly providers from the states of Ohio, Indiana, and West Virginia. And the whole goal of it was to say, “OK, what areas do we need solutions around and evidence of what works? And what are those solutions we need to start working to find?” Because, I think, the thing that’s important to understand is, you know, there is $50 billion in settlement funds going to, now, this crisis—which is beautiful and which is wonderful—but we have seen this play out before.

The tobacco crisis is a great example where all these resources come into states or into communities, and then they’re used in other ways rather than used to actually help the people who were harmed by what happened. Or they’re used in ways that don’t actually work. And so, what Notre Dame has been championing is, we want to make sure we are linking arms with these communities, and we are doing the research on what they’re investing in so we can quickly have them pivot if we’re finding something doesn’t work. And if they find something does work, they can do more and more and more in that space.

And so what came out of August was a research agenda that the academics and the states did together to say, “This is what we need to find out.” And now, what we’re going through is a process of actually getting all of that research launched so we can learn what works to support those communities who have been devastated by this epidemic.

Jenna Liberto:

Sadly, one of those perfect examples you mentioned, West Virginia—members of our team behind the camera here today traveled to West Virginia to work with, or hear the stories of, one of our alumni working in this area. I would say, hearing their stories is eye-opening, to say the least.

Paul Farrell:

The opioid crisis destroyed this community. We call it Ground Zero for a reason. This wasn’t a wave, this was a tidal wave. A tidal wave of pills into communities.

Jenna Liberto:

The voice you hear is Paul Farrell, a ’94 Notre Dame graduate who has become a prominent trial lawyer in West Virginia.

Paul Farrell:

In my hometown in Huntington, Cabell County, West Virginia, we have 100,000 people. We are averaging 10 million pills a year.

Jenna Liberto:

In 2022, he led groundbreaking litigation that led to a number of states and communities accepting a $26 billion offer from opioid manufacturers and distributors.

Paul Farrell:

This is pharmaceutical-grade opium. It’s claimed the lives of my friends. It’s claimed the lives of my friends’ children. My neighbors. You will not find anybody in this community that has not been impacted. What I’m trying to do is, I’m trying to fight for not only those that were lost but fight for the children of those families. What we needed was the city, the county, and the state to each join hand-in-hand and take this fight on.

We didn’t want the opioid litigation money to be used to retire state debt. We didn’t want it to be used for infrastructure, for roads, for schools. As bad as that sounds, I, personally, wanted to make sure this money was spent to fight the opioid epidemic, and that’s where I’m hoping LEO and the University of Notre Dame can play a role.

Heather Reynolds:

Eye-opening. And, I mean, you know that Paul Farrell, he is such an incredible Notre Dame alum. His expertise is in legal, and what he has done, I think, is a beautiful representation of what it means as an alum to be a force for good in this world.

But he has really helped ensure a lot of settlements have happened that are helping us solve this crisis across the country, but specifically in West Virginia. So yeah, when you see the unveiling and the impact on people’s lives, it’s pretty haunting. It’s hard to argue with the fact that the work needs to be done and strong partners need to emerge, which is happening.

Jenna Liberto:

That’s right, and I’m glad you mention partnership because I think that’s one of the really unique features of LEO and, I would argue, Notre Dame at large.

Heather Reynolds:

You know, one of the things that I love about this place is the way we live out our values. And so, instead of LEO being researchers who just do cool research here on this beautiful campus of Notre Dame, no, we go find the partner, we answer the questions they want to ask.

And so, like in the case of West Virginia, there’s a lot of stuff we’re doing with Catholic Charities in West Virginia, who’s on the ground in it day-to-day and understands what needs to be done. And where they’re bringing to the table knowledge of their community and knowledge of how to serve, we’re bringing to the table our knowledge and our toolbox of research.

Jenna Liberto:

I’d love to kind of wrap up our conversation talking about the larger effort on our campus that has emerged, and you mentioned it earlier, the Poverty Initiative. This is work that’s happening in many parts of campus—LEO, certainly. But what does that commitment by Notre Dame, itself, mean to you?

Heather Reynolds:

Yeah, I mean, it is . . . my life is committed to poverty, but what I have seen this University do now under the leadership of our provost is say, “We’re prioritizing creating a world intolerant of poverty. We are prioritizing that it is not OK that so many people in our nation and across our globe are struggling in poverty. We believe in human flourishing, and we believe if people are going to flourish, they need to live a life outside of poverty.” And so, Notre Dame hasn’t just said, like, we care about . . . I mean, Notre Dame has always cared about this issue, right, but what we have said is, we are prioritizing it.

So we are going to recruit the best faculty across this world to come to Notre Dame because we are going to make sure that the brightest minds and the brightest scholars are answering these questions here. We have said we are going to invest an unprecedented amount of resources in our current faculty here and in our centers here and in our institutes here that are zoned in on creating this research in partnership with nonprofits and partners across the globe so we can actually use that research as an input to have major global impact.

I mean, that could not be more exciting and gratifying and humbling to think that we get to be a part of those things. It’s exciting. And so do our students—our undergraduate students, our graduate students . . .

Jenna Liberto:

Yes. Yes. That gives me chills to think about. Your energy. This research. This commitment. And then, they take it out into the world.

Heather Reynolds:

Yes. Yes. Yes, yes, yes. It’s great so . . . and, you think about it in both ways, like our undergrads, I mean, they’re amazing to begin with, right? And they come to this place super skilled, super excited, and super ready to be formed in the way—you know, [they] chose Notre Dame because they want to be formed in the Notre Dame way.

And what we see again and again at LEO, I can talk specifically about, is these students who want—who are brilliant in math and stats and economics—and want to actually use those skills to help the poor. And, you know, all of us have done the things that are wonderful to do: to go to the food pantry and help bundle food, to go to the soup kitchen and help feed the poor, and those are all good and important and worthwhile things in the world. We’re developing this next generation of poverty fighters but they’re getting a sense of, they can do it not just on the side but they can do it as part of their vocation.

Jenna Liberto:

Heather, we’re blessed by your energy behind this really, really important topic and so am I. Thank you for talking.

Heather Reynolds:

Thank you so much for having me. It’s always good to talk to you.

Jenna Liberto:

Appreciate it.

You’re watching, or listening to, the Notre Dame Stories podcast. Don’t forget to subscribe wherever you get your podcasts.

In the second part of this episode, my conversation with Tracy Kijewski-Correa, the William J. Pulte Director of the Pulte Institute for Global Development. Tracy shares her deeply personal reasons for fighting poverty and empowering others to do the same.

Tracy, I’d love to start our conversation just hearing about your Notre Dame story, so tell us how you got here, and then, into the role you’re in now.

Tracy Kijewski-Correa:

Yeah. Pretty unique Notre Dame story. So, I’m a triple Domer, and I come from a community that is deeply poverty-afflicted and crippled by violence—largely gang violence—just on the south edge of Chicago. So, as a young girl, my grandfather set this goal that someone in our family would make it to Notre Dame. We worked hard and we espoused that vision. My high school lost its accreditation, had a lot of challenges, and I always tell people Notre Dame took a chance on me by admitting me, and then I was blessed once this world opened. And I think that hard work and hustle materialized in three degrees.

So I spent 10 years straight working all the way through my Ph.D., but, I think, ultimately, that hunger, as I tell people in my Notre Dame story, and what brought me, ultimately, to the Keough School, was probably imprinted in my brain when I was 10 years old. I watched the Mexico City earthquake. And I watched all these buildings collapsing and, I remember saying to my grandfather—who was, again, this pivotal role model who really steered me toward Notre Dame—how could this happen?

But then, coming full circle, as I worked through my degrees at Notre Dame and, eventually, my early career here as a faculty member, I started to realize that, oh, it’s much bigger than the science and the engineering parts. Of how we build communities, for example. There are these other dimensions, poverty being at the core, and so, I eventually migrated to the Keough School where I had permission to ask “Why?” in a much bigger way than, maybe, I would have traditionally done if I just remained as just an engineer—not that I don’t love being an engineer—but a different breed of engineer.

So a wild Notre Dame story. It’s now, I mean, gosh, over 20 years on the faculty, 10 years in education building up to my Ph.D. So a majority of my adult life—I’m almost 50—I’ve been at Notre Dame.

Jenna Liberto:

Thank you for sharing that story. How does your unique experience, maybe, give you a different perspective with your students that may come from a background like yours?

Tracy Kijewski-Correa:

It does.

Jenna Liberto:

Or may have a very different experience?

Tracy Kijewski-Correa:

Yeah. And I think, you know, for me, that’s been one of the blessings of Notre Dame. We have this open-door policy and this permission, because of our size and our commitments to undergraduate education and graduate education, to know our students as a human—as a person—and not a Social Security number.

And that’s what I always tell people. People opened their doors and saw me, saw the potential in me, and I remember how that changed my life and made a Ph.D. possible for a girl who was trying to get to college, right? And I speak from my own experience. I candidly share how difficult it was to transition to a university like Notre Dame from my background. Being a first-gen. Coming from a minority-majority, you know, town where no one at Notre Dame was much like the friends I had back home, and what that meant for adapting to this environment and flourishing here.

Jenna Liberto:

Tell me about the work you’re doing now, your professional experience, and what gives you the most energy?

Tracy Kijewski-Correa:

So, as I told you, there was that pivotal earthquake in Mexico. I was 10 years old. And I think, as a little girl, those moments of destruction, they always ask me “Well, why?" My brain’s like, “Why is that happening?” And so, I gave my career, I’ve given my career to studying how we build more resilient communities. Communities that can handle shocks like disasters and other crises.

Well, to do that, I actually have to go to communities on their darkest day. So I show up the morning after their worst crisis, and when you arrive on a community’s darkest day, that’s heavy work. It’s easy to actually see everything that didn’t work that day, and all the destruction around you, and say, “There’s no hope.” So what energizes me is the fact that, in each of these communities and everyone I engage in those communities, they actually have the answer inside of them.

But as academics, we don’t always pause to invite that answer from them. What I found in going to communities: If you deeply listen, and you invite them into discovering what happened with, you know, last night and how we rebuild for tomorrow, they always have the answer inside if you help them find it. And that was one of my best moments working in Haiti.

Walking down the street with a young man who we’d been working with in community workshops and he said to me, “Last night, my mother asked me where all these ideas were coming from.” Apparently, he was talking at night to his mother and he said, “Mom, the answer was always inside of us but no one bothered to show us.” I think that’s how we make breakthroughs in the world and that’s what excites me most, right? It gives me a lot of hope when I work in dark moments.

Jenna Liberto:

Can you talk more about those moments where you’ve seen that realization with someone you’ve worked with, maybe an example of what that looks like—to understand that someone has a key to make their community better.

Tracy Kijewski-Correa:

So I’ll go back to Haiti because that is one of the most challenging environments I’ve worked in professionally, and if folks are, you know, remembering the 2010 earthquake, it claimed over 300,000 lives, maybe more. And where Notre Dame had been working, it was a town called Léogâne, it was the epicenter. Ninety-five percent of all the buildings and everything just collapsed, so they were living in devastation. In a five-day period, we were doing a community workshop to try to conceive solutions to what, at this point, was a housing crisis.

And as the workshop began, you could see the power dynamic. Here’s a group of professors and students from Notre Dame, and you could see the Haitian community members, we had a whole process for how to assemble and invite the right minds into the room, not based on education, but their ability to innovate and find a creative solution. But even in those first 24 hours together, they were waiting cautiously for us to lead. And by day three, they had the markers—the Sharpies—in their hands and they’re drawing on the wall diagrams and ideas, and we’re out of every picture.

And, you know, in Haiti, I am coming from a position of power, and what they characterize as the “blonde,” the “outsider,” the “white,” right? And so, there’s so many dynamics in play that would cause that caution, but by the way we configured our participatory process, they took the marker in their hands and the best pictures I have is the feverish drawing and ideas flowing. And by the end of the week, they were singing and celebrating this kind of idea that they had the solution.

So we leave, that five days, we get what we hoped and needed from that event, which was identifying some of the pathways to rebuild, but then we found out that they kept meeting after we left. They founded 120-member-strong “innovation clubs” as they called them. And they started tackling many problems in their community that weren’t part of the original scope. And then you realize, we had ignited a fire. Just because we created a process that invited all voices to be heard.

Jenna Liberto:

It occurs to me there’s a parallel between you seeing that potential in someone and, I imagine, someone—or someones—did that for you.

Tracy Kijewski-Correa:

Absolutely. Absolutely. And I think that ability to see human, and all their full dignity and potential, regardless of their status or stature in life, can be the game changer, but, you know, Paul Farmer—the late Paul Farmer—he had a quote, and I might misspeak, but I think it goes something like this: “The root of all that’s wrong with the world is that we value some lives more than others.”

Jenna Liberto:

Let’s talk a little bit now about the Keough School of Global Affairs, specifically, and the unique role that this school plays in a broader fight against poverty that’s coming from our University. So what is that piece that’s unique about Keough?

Tracy Kijewski-Correa:

Yeah. In my mind, there’s three elements of this. You know, poverty touches education, issues of migration, the climate and the environment, you know, health. There almost is no dimension of human life that isn’t touched, in some way, by poverty. Either driven by it or perpetuated by it. So the fact that the school’s interdisciplinary is the first, I think, pillar of this.

The second, though, is that we also like to remind people in the Keough School that our mission, or our understanding, is that poverty is not material deprivation, which we commonly say, “Oh, you live below the poverty line.” There’s so much more to that. It affects emotionally, socially, psychologically, spiritually—every part of a human experience.

And so, we don’t want to talk about poverty in terms of raising income, we want to talk about poverty with respect to promoting holistic human flourishing. Here in the Keough School, we call that integral human development, but the premise shows us that when you focus only on the material aspects—we meet your immediate material needs—you still don’t feel empowered and resilient and capable of continuing to fight to build a life out of poverty.

And then the third is, as a global school, we’re looking at these issues around the world. Comparatively but, also, understanding our charge to look at the whole human family across the planet, and yet, we balance that in this school with the idea and understanding that you must think globally but then work locally. And only by working on the ground and seeing the unique manifestations of poverty and how that’s played out with the context and history and culture of a place, that’s the only way you’re really going to be able to address poverty issues. And I think that’s one of the parts I’m most proud of is our spirit of accompaniment, going deeply in communities and building the relationships like the ones that my work has benefited from.

Jenna Liberto:

Can you talk a bit about the piece of this that is working with policymakers? And Notre Dame has a great history in working across political thoughts to solve problems that the world needs solved, so talk about that piece of this work for you.

Tracy Kijewski-Correa:

Yeah. I think, you know, for conversations with policymakers, the first thing they’re looking for is a trusted partner, as you know. Notre Dame has that brand and that part is easy. The second is, they’re just really curious about what works and what doesn’t. There’s so much talk about cost-effectiveness of federal investment in areas of importance for our country and our world and, being able to show them what works and what doesn't and why, is what every lawmaker, every policymaker is seeking, is eager to hear.

I think the second part about what we do, uniquely, in the Keough School, and I’ve seen lawmakers respond to positively, is that we’re also giving—because of that local focus—we’re bringing local voice to them so they hear boots on the ground. And they’ll often say they get statistics and reports and briefings all the time, but when I can then bring that unique local perspective into that briefing, they understand then how it’s being implemented on the ground. Where those barriers are, and those human dimensions that are being missed in cold statistics.

But the second challenge for a place like the Keough School and the Pulte Institute, which I direct, is that change isn’t only made in DC. When you work across 70 countries on the planet, how you move evidence or interventions that are promising into scaling up and into action means you’re building a robust network of partners of influence. And whether we’re seeding change with teachers and schools in a community, or all the way up to the Ministry of Education, we want a robust infrastructure that gets that evidence in their hands.

Jenna Liberto:

I want to ask you, Tracy, before we wrap up, you’ve so beautifully shared your “why” for this work, I’d like to hear your perspective on why Notre Dame? Why is it so important that our University is involved with the work that is so near and dear to your heart?

Tracy Kijewski-Correa:

You know when we were conceiving what, ultimately, became the Poverty Initiative, the “Why Notre Dame?” was such an easy question to answer from just a moral calling. A great Catholic university should be leading on issues of poverty, and uniquely leading . . . I had a friend once—a National Academy member—tell me, “I’m so jealous of Notre Dame because they have the moral compass to answer questions, even bring the role of faith and other dimensions into questions, like poverty issues—like poverty—but then the credibility to bring the evidence that means you won’t be locked out of the room when you say that.” And I think that line that we walk, perhaps, that keeps us very kind of middle-of-the-road and a trusted partner no matter what the political climate. That’s a really important part of just our call and our responsibilities of great Catholic university.

But then the second thing, you know, that we have is this global network. The “Why Notre Dame?” If you’re going to think global but then work local, you need an expansive network of partners that you’ve poured into and you’ve built a relationship with. And that’s something we’ve been very good at, and a big part of that is the global Catholic Church. It gives us a reach to scale and move forward in ways that other universities can’t, and I think it’s largely untapped.

And now I think we’re leveraging it in new ways, including our Alumni Network, right, another layer of our power and our reach. We treasure the local voice. We want to accompany communities and those partners. And only by having them at the table from the very beginning, taking that network local, right, deeply local, I think that’s how you can affect change that many universities, maybe, don’t have the patience or even the . . . or don’t honor the local voice as much as we do and, therefore, miss that powerful opportunity.

Jenna Liberto:

Tracy, lastly, what would you tell that girl who didn’t feel quite prepared to be here?

Tracy Kijewski-Correa:

Wow. That’s a heavy question. I would tell that girl to believe you’re called, and you just have to be quiet enough to hear the calling. There are many days that that little girl is still scared inside this woman, and what I always remind her is there’s never been a moment, even in some of the most turbulent places I’ve worked around the world, that if I’m quiet enough, I’m not directed to what the next step should be.

And people ask me, “How do you not break down when you’re in the middle of some of these places and the things that I’ve seen?” And I said, “Because I get quiet and I pray and say, ‘Show me the next step.’” And I have faith that that’s the next step and I’ll receive instruction on the next step. And life has just opened up every time I’m quiet enough to trust that. And so, I’m glad she was quiet enough to trust that. I’m thankful Notre Dame took a chance on me and has had faith in me, and I’m thankful that every day I get a message of what’s the next step.

Jenna Liberto:

That’s such great advice for work and, certainly, for life. Thank you.

Tracy Kijewski-Correa:

Yeah, no, absolutely. Thank you. Thanks for your time.

Jenna Liberto:

If you love the What Would You Fight For? series, there’s more online. And if you’re interested in the Notre Dame Stories podcast, which we hope you are, subscribe wherever you listen to or watch your podcasts.