Read the transcript

The transcript has been formatted and lightly edited for clarity and readability.

Introduction:

For the 15,000 patients in the world who have Friedreich’s ataxia, a rare genetic disorder, a cure seems far off. The disease rarely gets funding or attention. But scientists at Notre Dame’s Boler-Parseghian Center for Rare Diseases are researching 15 different rare diseases to find treatments and improve the lives of patients and their families. What would you fight for? Fighting for those with rare diseases. We are the Fighting Irish.

Andy Fuller:

Another installment of this season’s What Would You Fight For series, that was “Fighting for those with rare diseases.” Welcome to Notre Dame Stories. I’m Andy Fuller.

Jenna Liberto:

And I’m Jenna Liberto. Andy, first of all, I want to start at the very beginning: What is a rare disease? What qualifies a rare disease?

Andy Fuller:

Yeah. In the US, a rare disease is defined as a disease that affects fewer than 200,000 people. So it’s a fairly small percentage of the population. However, there are 8,000 such diseases that we know of, so if you do the multiplication there, about 1 in 10 people are affected by a rare disease.

However, these people are very underserved by the medical community. A lot of time, these diseases are called “orphan diseases” because no one will take them on. There’s not incentive for drug companies, say, to develop a treatment for these diseases because so few people have it, if that makes sense. So they need someone who will take on that research and will fight for them, and they find that at Notre Dame.

Jenna Liberto:

Yeah, an underserved group, an unmet need, that feels like very good work for Notre Dame to take on. That feels very within the wheelhouse, right? Yet, we don’t have a medical school here, so it’s a bit surprising to me, at least—I’m sure to others—that this kind of medical research is happening on our campus. That’s exciting.

Andy Fuller:

Yeah, it is. And it comes right back to the mission, right? You know, the series is called What Would You Fight For? and, a lot of times, you have to have a personal involvement to want to fight for something. That’s certainly the case with the dean of the College of Science, Santiago Schnell, who’s also in the two-minute spot that airs during home football broadcasts on NBC.

He has a family member who was affected by a rare disease, so he definitely has a personal investment in this work. And a lot of times, these diseases come on our radar because a loved one will pick up the phone and say, “Hey, my kid just got diagnosed with this. I’m not finding any information; can you look into it?” And oftentimes, we will have a researcher here on campus who says, “Yeah, all right, I’ll take it on. I can see what I can find out.”

And that really does speak to mission. You know, people are here because they want to be a force for good. They want to use knowledge to help solve some of the pressing issues, especially for folks who are marginalized. This story really plays up those elements quite a bit.

Jenna Liberto:

There have certainly been some successes affecting families’ lives right now: quality of life, finding community. What are the other successes that are being seen already, or are there some?

Andy Fuller:

Yeah, you know, one of the first diseases that the center took on was called Niemann-Pick Type C. I’ll leave the experts to explain what that is and what it does, but the good news is we’re moving close to a trial for an actual drug treatment of that disease. That takes a long time to reach that point, however. In the meantime, what these folks who are dealing with these rare diseases—and their families—what they need is, they need someone to advocate for them as they navigate these different kind of complexities of the health care system and just, you know, “Where do I find answers? Where can I find community?”

And that’s the other part of this story that we didn’t have time to get into in the two-minute portion that you see at halftime of football games, but we’re doing it here in this podcast—and that is the Patient Advocacy Minor here at Notre Dame. That really kind of teaches our students: This is how you look out for someone as they go through the health care system with this thing that they’re dealing with.

Jenna Liberto:

I’m really interested to find out how unique that is. I’m going to talk to one of our experts here on campus about how a rare disease gets connected with a researcher at Notre Dame, and then dig more into this patient advocacy angle and the impact that has here on campus and beyond. And these are both people that were not in our original two-minute piece, right? So, new conversations, I can’t wait to have them.

Barb, thank you so much for joining me. It’s great to be with you.

Barbara “Barb” Calhoun, Reisenauer Family Director for Patient Advocacy Education and Outreach; Director of Minor in Science and Patient Advocacy:

Yeah, thank you so much for having me and to be able to share this with you.

Jenna Liberto:

I’m so curious to hear about your background and what brought you to Notre Dame. So, we’ll start by asking the question that we ask all our guests, and that is: What is your Notre Dame story?

Barb Calhoun:

So I am a nurse practitioner by training—in pediatrics—and we moved here and I just thought I wanted to find something unique, different. And then I saw the advertisement for the job with the Boler-Parseghian Center for Rare Diseases, and it was for an outreach coordinator, and the whole role was to bring patients and families to the researchers and, along with that, to engage the students with the patients. I thought, this is fantastic.

So in 2014, I took that job, and I have been doing it ever since.

Jenna Liberto:

And you were telling me, before we started rolling, how unique this program—this work—is, being done on a college campus. I mean, coming from the medical field, was that part of that spark, like, “Oh, I didn’t know this was an option?”

Barb Calhoun:

Absolutely. And, you know, I have the clinical experience, but being at a university that doesn’t have a medical school, and identifying the many needs that rare disease patients have—I never thought that, as a nurse practitioner, that I could be involved in research and a university that focuses on the people that need it most.

Jenna Liberto:

And again, you mentioned we don’t have a medical school here at the University. Does that provide opportunities or challenges or both?

Barb Calhoun:

It actually, I think, is a good thing, because we are allowed to form academic programs based on how we feel the students would best be served. And as you know, rare diseases don’t have . . . there’s only 5 percent that have an approved treatment, so, it’s perfect to understand the symptoms by picking up a medical record and having the students summarize it. It culminates in a deep understanding of the diseases that we study, but then also can be applied to what they’re going to be doing in med school.

Jenna Liberto:

I’d love to talk a little bit about the minor that you’re now director for. So the minor in science and patient advocacy, there’s this research piece with rare disease and then this patient advocacy piece. So tell me about the program, then I’ll also invite you to maybe connect the two for us and how they go hand-in-hand.

Barb Calhoun:

So when I first started, you know, there were the two classes that I taught in rare disease. And the whole premise was to streamline the ability for more students to get involved. The first course is like I mentioned, it’s just getting them introduced to the clinical aspects of disease. We have students partner with the National Organization for Rare Disorders and they act as editorial interns, but then they help patients have the most up-to-date information and resources available on that website, because often that’s the first place patients will go when they’ve been diagnosed with a rare disease.

So then we progress on the minor, and we apply that knowledge that they learn from that into different advocacy avenues. We also have students partner with patients themselves, and that process is all about learning how to communicate effectively to understand the lived experience of the patients, but also to, together, then develop a story or a way to share their story.

Jenna Liberto:

Barb, let’s talk about your students who have gone through your program. What are you hearing about the experiences they’ve had here and what impact they’re having?

Barb Calhoun:

I had no idea the impact that this minor would have on students. One, I will tell you, was a student that graduated and she was a medic—an EMT—during her gap year, and she walked into this, there was a call, she went with her partner into this home, and the mom met them and said her son is ill . . . but she’s nervous because “you might not ‘get’ his disease,” and lo and behold, the child’s disease was discussed in class. She knew exactly what the symptoms were, voiced that to the mom, and the mom had such relief in the fact that she knew someone caring for her son actually knew about the disease.

But the one thing that I think is the best result of this is the students who call me from med school and ask how they can start a rare disease club or component to the work they’re doing at school and continue to be the advocate, regardless of whether they’re in medicine, public policy, or anything.

And one of the things I also wanted to mention is, we just started a legislative component to our education in the hope of building the ability to understand policy related to rare diseases. So my hope there, too, is to get them more involved in understanding that process so they can advocate through their legislators or work in the community. So, it’s fascinating.

Jenna Liberto:

Inspiring. That’s great. Knowing some of the challenges that families face, whether it be connected care or just finding community through diagnosis, you’re really training the next leaders who can make a difference.

Barb Calhoun:

Absolutely. And they are learning how you can, you know, access the most up-to-date literature, the most up-to-date research, find out who the experts of the disease are. Who is providing resources and services for that particular disease? It helps them to build their knowledge base and put it into action.

Jenna Liberto:

And I’d love to talk about one student who, I know, has been critical in sharing her story and learning from students and students learning from her. I’m remembering that Annie Hamilton, who was featured in our What Would You Fight For? piece that ran during home football games, she offers a perspective to your patient advocacy students about what it’s like to live with a rare disease.

Barb Calhoun:

So, you know, the What Would You Fight For? for Annie was a great representation of how we connect research and advocacy together. And the thing about Annie is, it’s not just about the disease, it’s about the resilience and the hope and the the impact that advocacy can have on driving research. I think the important thing about the story is that research is the scientific knowledge, as I mentioned, advocacy is ensuring that the patients are central to everything that we do. And, you know, when you introduce a patient to a student—and I say patient, they’re people—there is such an impactful real-life experience that kind of says, OK, the gaps in research compared to the lived experience by these families . . . it pushes them into meaningful action.

So they apply their academics to really making a difference. Dean Santiago Schnell with the College of Science, he’s been instrumental in making sure that we further develop this program. He is behind it 100 percent. Out of that video, we received over 60 to 70 different emails, and he received multiple emails. And if you read his response on those, it takes you aback because it is so heartfelt and genuine and proactive: “We can help you; here’s how we can do it.” And I, I just am in awe of that, but it actually drives me to work harder for these patients. You wouldn’t believe the variety of diseases that people call about and they just want just the littlest thing, just help. “I need some resources.”

So I believe that Annie’s story has done such a wonderful thing for knowing that Notre Dame is with all rare disease patients, and if we can’t find the resources here on campus, we will look for them and help you in other ways.

Jenna Liberto:

Was there an aha moment that you or your students had working with Annie that opened your eyes in a different way?

Barb Calhoun:

Annie is a beautiful person, and her whole family is wonderful. She came to my class last year, and I had 36 students in the class, and she sat in front of the class for an hour and 15 minutes and told her story. She had slides about when she was younger and the clumsy, cloppy kid and how the disease kind of came to fruition. But one of the things that really hit me was, we were talking about the clinical trials that are coming about, but she said—and this sits with me every day when I think about patient—she said, “I just want to be Annie.”

I just get chills with that, because that is exactly what we are trying to do through our work with advocacy. The term patients is kind of a catchall, but it doesn’t really describe the, you know, the lived experience of these patients, and they’re incredible and they’re resilient, and she’s dynamo. Yeah. Yeah. I love that family.

Jenna Liberto:

What inspires you most or impresses you most about a family like Annie’s?

Barb Calhoun:

They’re not going to sit and wallow. They don’t want your pity; they want action. And you either join them and help them, or they leave you behind because they’re not going to stop until they get their treatments or care. And with patients, they are . . . you know, people say this, that “oh, they’re the experts.” They are. They know day in and day out what it looks like. They know what challenges they face daily. They don’t have treatments. They kind of go on, you know, a wing and a prayer trying to hope that this is the right path, and I think that patients have taught me about being resilient and looking where I am now, but also looking to the future and not looking back.

Jenna Liberto:

And you mentioned that action, that it’s happening at Notre Dame, and it is so unique. What does that mean to you, personally, that the University of Notre Dame is so committed to patient advocacy?

Barb Calhoun:

You know, it is incredible. When I first started working, I met Cindy Parseghian, Mike Parseghian, and that was the first disease that we studied at the Boler-Parseghian Center. And it was there that I realized that Notre Dame has a true passion for helping those that are underserved, and the mission is about continuing with them through their journey. And Cindy’s a true reflection of that because, even today, she is here, she’s helping all these other families.

And it was because of her own loss of her three kids—and Mike, their three kids—that they truly needed to reach out, and Notre Dame was there. And so, you’ll hear from Sean later, but he has continued to be that arm for so many other families with Neimann-Pick.

I haven’t even mentioned, the research is phenomenal. You know, there are 15 different rare diseases that we study, and the more that we engage with patient families, the more that I think the research comes this way. When you go into a research conference and you listen to the—you know, I’m a nurse practitioner, so it gets a bit dry for me—but, when you see them, when you see the researchers, see the patient, it brings about a whole different level of drive. I’ve seen that at Notre Dame.

From one rare disease to now 15 in my time that I’ve been here.

Jenna Liberto:

Before we finish our conversation, Barb, what you just said—it occurs to me, all these different touchpoints that make it personal, and something you said earlier about your dean, Santiago Schnell, it starts with him. This is a very personal fight for him.

Barb Calhoun:

Dean Schnell, he actually is a role model for how we all should be, regardless of whether we have a rare disease or not. The compassion that is shown—I really have learned so much since he’s become the dean, and how to not dwell on the issues that are within your own but to look beyond and utilize the experiences that you’ve had to help.

And I think that Dean Schnell, not only is he a brilliant researcher, but he also has daily challenges that inform how his day is going to go. And that is so what all of these rare disease patients deal with on a daily basis. So, his leadership is more than just, you know, “This is a program, we need to keep it going.” No, his passion is in it and I feel it. And it’s a wonderful place to be when your leaders want you to continue to do what you love to do so much.

Jenna Liberto:

Barb, thank you for taking the time to talk about your work, and let’s talk again in the near future.

Barb Calhoun:

Absolutely. Thank you.

Jenna Liberto:

Can’t wait to hear more. Appreciate it.

During our previous interview with Barbara Calhoun, you likely noticed a couple of references to Professor Santiago Schnell. In our forthcoming interview with Sean Kassen, he’ll be cited even more. So, before we continue to that, it’s worth pointing out that Professor Schnell is the William K. Warren Foundation Dean of the College of Science here at the University.

Widely considered a distinguished scientist and academic leader, he earned his undergraduate degree in Venezuela and his doctorate at Oxford. He came to Notre Dame in his current role in 2021.

Santiago Schnell:

Esa es la llamada que me trajo a Notre Dame. Aquí buscamos el conocimiento queue nutre el espíritu humano. Me inspira tanto su valentía como la fuerza . . .

(That is the call that brought me to Notre Dame. Here, we seek knowledge that nourishes the human spirit. I am inspired as much by your courage as by your strength . . .)

Jenna Liberto:

In addition to his many other scientific duties here at the University, Santiago is especially motivated in his work researching rare diseases because of tragedies that played out in his own family. While facing the heartbreak and despair caused by losing loved ones to rare disease, Santiago still holds on to the courage and the strength his family found in each other during those times. That’s his ongoing motivation.

Santiago Schnell:

I’m Santiago Schnell. I’m fighting for those with rare diseases.

Jenna Liberto:

Sean, thanks for talking with me, appreciate having you here.

Sean Kassen, Director, Ara Parseghian Medical Research Fund:

Absolutely.

Jenna Liberto:

Tell me a little bit about your Notre Dame story. How did you get here?

Sean Kassen:

How did I get to the University? Well, it’s a long story. A long journey.

Jenna Liberto:

Tell us some of it.

Sean Kassen:

Well, let’s start. So, I actually grew up all around the Midwest. I was born in Buffalo, lived in Philly for a little bit, then ended up in between Northern Detroit suburbs in a little town called Oxford, Michigan. And the reason I did that is because my dad was a Lutheran pastor—now retired—and so he moved all over the place. So I actually grew up Lutheran, not Catholic. We call that “Catholic Lite” where I’m from.

So my parents, you know, Midwestern parents said, you know, “Just go to college, get a job.” And then at the last moment this guy I went to school with, who was my future roommate in college, said, “Hey, I’m going to this small school in Michigan called Alma, why don’t you just go there and be my roommate?” And so I applied, I got in, and I went there. And, actually, the first day I moved in was the first day I ever saw the campus, but that was kind of how I was.

But then, all of a sudden, things started to click when I got into college. I met my future wife there, a lot of my closest friends—and I ended up getting passionate about science and I got a degree in biochemistry. So, afterwards—like my mom told me, “Go to college, get a job”—I ended up just being lab tech at Evanston Hospital. And so, I wasn’t thinking about grad school until that moment after about two months. I knew if I wanted to pursue science, you’ve got to have an advanced degree. So you have to have a Ph.D.

Notre Dame’s graduate recruitment weekend was the same weekend as Emory’s, and I went to Emory’s and I skipped Notre Dame’s. But David Hyde, who’s a faculty member here, said, “No, just come next week, come visit.” I came and I loved it. And so, I ended up being accepted here. I stayed here. That clicked. Science clicked with me and I ended up finishing my degree in, actually, four and a half years; I had a number of publications, had a lot of great mentors.

My wife then found . . . moved, you know, left journalism and moved here and took a job in the Development Office. And she was telling me, “Hey, they’re looking for a scientist that they can train to be a fundraiser to work in corporate relations.” So I ended up applying for that and got it. And then, eventually, I ended up as what was called an academic advancement director for the College of Science where you oversee all the fundraising efforts for Science. Did that for a number of years, and one of the main areas we were raising funds for was rare disease.

And that’s how I got to know the Parseghian family, learn about their journey with rare disease. They had an external foundation that they merged with the University about eight years ago. When they did that, since I knew them, they asked me to run that, and that’s what I’ve been doing ever since. So I’ve been at Notre Dame for over 20 years. It’s a long story, sorry.

Jenna Liberto:

It’s great. From a kid who didn’t like to do homework to being so ingrained in such an important research arm of the University. Let’s talk more about the Boler-Parseghian Center for Rare Diseases. For someone who might not be as familiar, just tell us about this group, this organization.

Sean Kassen:

So the Boler-Parseghian Center is a center that’s focused on many different rare diseases. And when I started over 15 years ago, there was just the Rare Disease Center, and so, one of our activities was trying to raise an endowment for that. And we knew the Parseghians, but we also met the Boler family, and they’re the ones that eventually made the gift. What I’ve been running most of my time here, actually, is the Parseghian Fund, which is focused on one specific disease called Neimann-Pick Type C.

Jenna Liberto:

We talked to Barb Calhoun a little bit about the huge number of rare diseases that exist. It all started with the one for us here at Notre Dame, Niemann-Pick Type C, so yeah, tell us about that specific disease.

Sean Kassen:

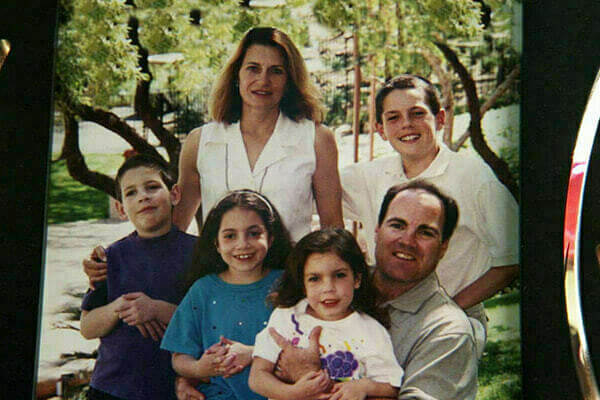

So, I mean, it’s just an awful disorder. What happened with the Parseghians . . . so there’s Coach Ara Parseghian, our famous two-time National Championship coach; son Michael married Cindy. So Cindy Parseghian is the daughter-in-law. They had four kids and they were living in Tucson—so Ara, Michael, Marcia, and Christa. Their youngest son, Michael, in the early ’90s, what they started to notice is that he just wasn’t keeping up with some of the other kids on the playground, you know, when they’d be playing tag. He would trip a little bit or, you know, he would just lose his concentration.

And typically you go to the doctor, you go to your pediatrician, and they say the same thing: growing pains. He’ll grow out of it. You know, a mother’s intuition kicks in after the third or fourth visit, something’s wrong. And I think it was almost like 10 doctors later they ended up at Columbia. And it was a couple years later where a doctor looked at Michael and said, “You know, I think I know what this is. It’s called Niemann-Pick Type C. It’s rare and it’s genetic and it’s fatal, and you need to test all your kids.” And on that day, because of genetic testing, they found out that three of their four children were going to pass away from this awful disease.

Jenna Liberto:

In one day?

Sean Kassen:

Well, on the same day they got the genetics . . . they found this out. I mean it’s, usually, children are diagnosed at 4 or 5 years old and then, you know, lose their ability to walk and talk. And by the time they’re teenagers, they pass away. We are diagnosing some older patients now. But what the disease is itself, it’s what’s called a, you could say, a cholesterol storage disorder—a lysosomal storage disorder.

And, basically, what the Neimann-Pick protein—NPC protein—does, it clears cholesterol in and out of the cell. So, when it’s not working properly, cholesterol builds up inside the cell . . . especially in your central nervous system and your liver, your tissues, and they start to fail. And that’s why these kids lose their ability to walk and talk—get seizures—and, usually, they succumb from, like, a pneumonia or a choking event, and it’s pretty devastating. So what [the Parseghians] did is, they launched the foundation.

And, I mean, at the time, nothing was known about this—I mean zero. You know, I think there were two scientists in the entire world that had been doing any research on this disease. But because of their broader community—Notre Dame community, their community in Tucson—they were able to raise funds, they were able to use Coach Parseghian’s name, and they supported a lot of research, and they’ve had a lot of breakthroughs. I mean, they discovered what the gene was. They didn’t even know the genetics behind it . . . All that’s a lot more common, but back in the ’90s, it wasn’t. And then, they understand the fundamental pathway, they did a lot of work on that. They’ve created a bunch of animal models and now we actually have therapies in the clinic, and we’ve had a few approvals of recent, so there’s been a lot of progress. But, sadly, they did lose their three children.

But you know, a lot of times what happens when a family loses a child is they sort of become less active in the community. [The Parseghians] didn’t want that to happen, so that’s why they merged it with the University, and I would say our fundraising and our research are accelerating now because of it.

Jenna Liberto:

And what’s it like to work with a family that is as personally motivated as the Parseghian family and the families that you work with?

Sean Kassen:

I love it. When I took over this role, it was what I was most nervous about because I don’t have a child with that disease. When I go home from work, I’m not living it still, where they are. But, at the same time, it’s so motivating. You know, what stresses me out at night—what keeps me up at night? It’s when you know that something didn’t go right for a family. When we were trying to get a therapy approved and it doesn’t get approved. You know, that burden on the families, that’s what keeps you up at night. You’re working to help them, but also, it’s exciting when you do get approvals or when you think you have something that could be a game changer.

You’re not doing it because you’re thinking, “Oh, we can start a company and make profits” or “I can publish,” you’re doing it because “I get to call these families and tell them this.” That we have something good in the pipeline that might help them. So I love it.

Jenna Liberto:

And we will talk about the breakthroughs, and I can’t wait to do that, but before we go there, tell me how Notre Dame finds the families or the families find Notre Dame, and then, how the research starts. That’s a pretty critical connection.

Sean Kassen:

So it actually started when there was a scientist here—so one of our strengths at Notre Dame is our medicinal chemistry group. These ones make small molecule therapies and they’re really good. One of the faculty members, Paul Helquist, he sort of had this vision of a Rare Disease Center. That’s where this came from like 20 years ago. But eventually, Paul and . . . they got together, Cindy came to talk in front of a bunch of faculty and that’s how that research started to happen. Like . . . these two ideas get married together and now we’re starting to apply it to other rare diseases.

Oftentimes, you know, different families in the community, the Notre Dame community, will reach out and say, “Hey, we’ve been affected by this disorder,” you know, “Are you working on it?” Or, you know, “At least can I make you aware of it? Can you help connect me to a clinician or some scientist?” And we try to help them as best we can.

I even was going to say this last thing: One of the NPC families we’ve become really close with, my wife and I actually went to Disney World with them last May and, to be honest, we didn’t bring our kids. We just went as adults and we just went with their family. And we tell them, you know, we wish we didn’t know you because we know why we know you, it’s because of this disease. But, at the same time, they’ve become such close friends for us so we love it.

Jenna Liberto:

So I don’t want to oversimplify, but it does sound like, at times at least, it is as simple as a family makes a phone call, and you have a researcher that has an interest or an expertise, and the connection happens?

Sean Kassen:

Yeah. And, you know, if we can and there’s that connection, we love it. If we don’t, I mean, we only have a few hundred scientists here and there’s thousands of rare diseases so, if there’s something that we’re not doing here, you know, can we connect them to somebody in our broader network? We want to at least be able to help them out. It’s very impactful when you can make that connection for a family who is just lost.

Jenna Liberto:

And how big an impact does Dean Santiago Schnell have on what we’re talking about, those personal connections? Notre Dame raising its hand and saying, “We’re here with you. We’ll help fight this with you.” He’s got to be inspiring.

Sean Kassen:

Well, he’s affected by a rare disease, and just said he’s made this one of his top priorities. We do this annual fundraising event and the first time he just started—actually, before he actually started—he came out to our event and spoke. And he did such a good job, he got a standing ovation. Every time he speaks, he gets a standing ovation. I’ve never gotten a standing ovation. It’s just because he lived it.

I try to show up to work every day and say, “What can I do? How can I listen to someone like Santiago and really build on that? And how do I do some incremental advancements every day?” And usually, it’s because you’re working for those people: Santiago, and then the families, and then the scientists that you’re trying to help, and the clinicians that are answering emails at like 2 in the morning because they’ve been in clinic all day. Those are what motivates you.

Jenna Liberto:

Let’s talk about the breakthroughs. Because they’ve happened. And that has to be just—well, tell us about that. What’s that feel like to have something that you can say, “Our commitment, our research led to this.”

Sean Kassen:

Yeah. I mean, again, it was all that funding from the Parseghians: research they support and we’ve been supporting over the years to understand the pathway, how this disease works, how it manifests—all of that led to these moments. And we had some really tough times during this. We’ve had a number of therapies, one of the therapies that was approved three years ago, was rejected, and I can tell you we were in a really dark place.

One of the therapies, the FDA shut it down and a lot of families lost access to it. Again, those are the nights that you’re up late in tears with families because you don’t know what’s going to happen. But we were able to gather more data and go back to the FDA with these companies. And, I think it was September, I forget the exact date at, you know, 10:45 in the morning, we still did not . . . We knew it was the date that the first announcement was supposed to come, and we were just waiting. Just waiting. Checking our phones. Checking our phones. We still weren’t sure what way the FDA would, if they would approve or just reject it. And at 10—I do know the time, 10:45 in the morning—we got that note, that “hey, here’s the new name,” because they actually change the names of the drugs once they’re approved. And we got the new name and we got the second approval. So we’ve been just on cloud nine since then.

And I can tell you, there’s a few more in the pipeline that we think we might get approved within the next 18 months. And what we’re working on here at Notre Dame right now, I would say, is the next generation that we think is going to be a game changer.

Jenna Liberto:

Now there’s a treatment available for Niemann-Pick Type C. What was the breakthrough that will now help families?

Sean Kassen:

So there’s two therapies that are now approved therapeutic options, and what they both do is they slow the progression of the disease and they also give better quality of life. You know, you might say a typical progression, a child might be diagnosed at 4 or 5 and they, unfortunately, pass away in their teens. We have children now that have been on these and they’re in their 20s, and they have jobs. So you see that, you’re hearing more of these stories happening, and knowing that they’ll never lose access to these therapies now is just, it’s amazing.

They send videos of them, like, in tears: “This is the first time I get to take this approved drug.” And so now, we’re kind of on the hunt, as I mentioned. It’s giving—buying—them time, and we’re going to find that game changer that will, hopefully, be that cure.

Jenna Liberto:

Why is it so important, would you say, for Notre Dame to be a force for good specifically in this area of rare disease?

Sean Kassen:

Because every patient deserves it. I mean, that’s as simple as it is. You know, a lot of times, when you talk about areas of science that are underfunded because they’re just rare, you’re supposed to say, “Well, if you work on this—like, NPC affects cholesterol; not only will it help NPC but it’ll help cholesterol diseases.” You’re supposed to say it impacts these other things and that’s great. My answer is: because these are kids. They have a disease. Somebody needs to fight for them. That’s what we’re going to do. I don’t care if it’s 500 patients, 50 patients, five, or just one. Someone has to do it and that’s what we should do. And they deserve it.

Jenna Liberto:

Thanks for your work, Sean. Thanks for telling us about it. We can’t wait for the next news item, right?

Sean Kassen:

Yeah. Hey, when that next one comes, we’ll celebrate, and then we’ll get back to work.

Jenna Liberto:

Very good, appreciate it. Thank you.

Andy Fuller:

Really incredible conversations. It’s why I love this series that we’re doing. So the Notre Dame Stories podcast is extending the reach, if you will, of the What Would You Fight For? series because there’s only so much we can get to in those two minutes, and this podcast series helps us get to the rest.

Jenna Liberto:

And they’re all great stories. If you love the What Would You Fight For? series, there’s more online. You can go to fightingfor.nd.edu. And if you’re interested in the Notre Dame Stories podcast, which we hope you are, subscribe wherever you listen to or watch your podcasts.

We’ll see you next time.

Thanks for joining us for Notre Dame Stories, the official podcast of the University of Notre Dame.