Austin Wyman ’23 was young when the mental health crisis hit home. A struggling family member reached out to a provider for help, but with no immediately available appointments, the relative soon had a mental health episode. The situation ended in the death of two of Wyman’s family members, and left the rest of them reeling.

Now, Wyman is working to ensure other families don’t experience that kind of tragedy.

Austin Wyman, de 23 años, era muy joven cuando la crisis de salud mental golpeó su hogar. Un familiar con dificultades acudió a un proveedor en busca de ayuda, pero como no había citas disponibles de inmediato, esta persona pronto sufrió un episodio de salud mental. La situación terminó con la muerte de dos miembros de la familia de Wyman y dejó al resto tambaleándose.

Ahora, Wyman trabaja para garantizar que otras familias no tengan que vivir ese tipo de tragedia.

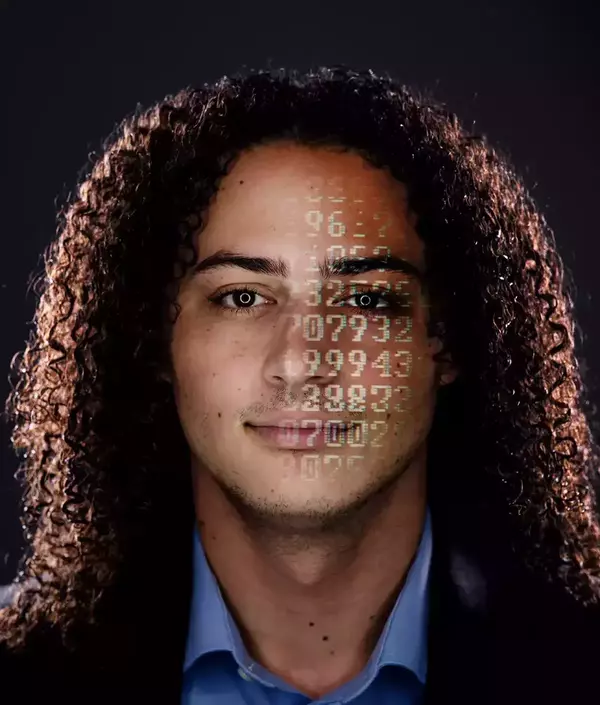

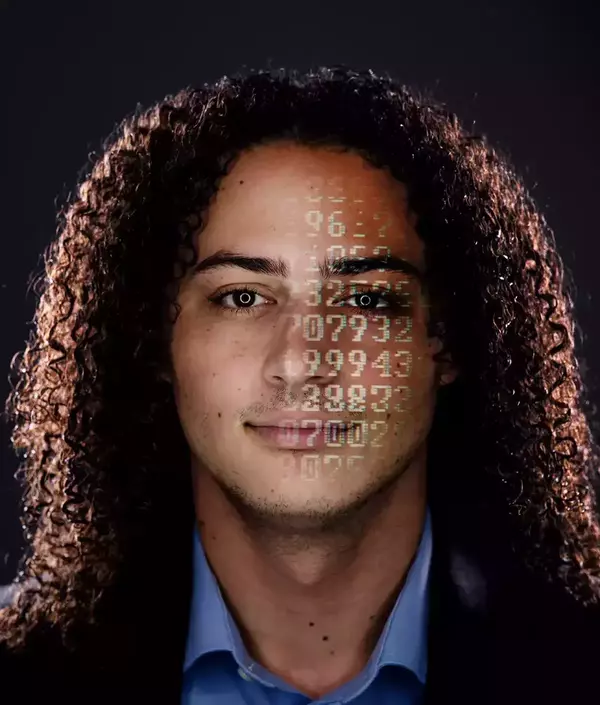

Wyman is a doctoral student in Notre Dame’s quantitative psychology program. The program trains students in statistical methods, quantitative models, and data science that can be applied to psychological research or methods development.

Wyman explained, “In biology and physics you have a lot of direct measurements, like you can see phenomena in the natural world and measure it. In psychology, we don’t have that luxury. We work with something called latent variables, which are variables that cannot be directly observed. And because they can’t be directly observed, you sort of have to tease them out in order to get the information you need from them, like you can’t look at something and say, that’s depression. No, you have to use indicators to understand that it’s depression,” he said, adding that signs such as irritability, low energy, and moodiness help indicate depression, but they aren’t certainties.

Wyman’s research involves using existing psychological questionnaires that help with diagnoses, and then applying artificial intelligence and machine learning to create new measurement tools to help streamline some of those subjective processes.

“The better measurement we have for things that we can’t see for the human mind, the better the research questions, the better the results, and just overall the faster the community moves,” he added.

He’s also working on a project to develop a psychological assessment that could identify police officer candidates who are less likely to commit misconduct. The research has captured his interest, and he’s hoping, at the end of his five-year program, to transition into an academic research career himself.

“I think it takes a certain amount of creativity to be involved in research, to see what has already been put out there and figure out what’s missing. It’s really satisfying to sort of fit in those missing puzzle pieces. It requires a lot of problem-solving,” he said. “Being able to think of my field and come up with new solutions that nobody else has thought of before, I think it could be really rewarding.”

Wyman es estudiante de doctorado en el programa de psicología cuantitativa de Notre Dame. El programa capacita a los estudiantes en métodos estadísticos, modelos cuantitativos y ciencia de datos que puedan aplicarse a la investigación psicológica o al desarrollo de métodos en psicología.

Wyman explicó: “En biología y física hay muchas mediciones directas. Por ejemplo, se pueden observar fenómenos en el mundo natural y medirlos. En psicología no podemos darnos ese lujo. Trabajamos con algo llamado variables latentes, que son variables que no se pueden observar directamente. Y como no se pueden observar directamente, hay que extraerlas para obtener la información que se necesita de ellas, de la misma manera en que no es posible observar algo y decir: "Eso es depresión". “No, hay que usar indicadores para entender que es depresión”, dijo, y agregó que señales como irritabilidad, bajos niveles de energía y mal humor ayudan a indicar depresión, pero no brindan certezas.

La investigación de Wyman implica el uso de cuestionarios psicológicos existentes que ayudan con los diagnósticos, y luego la aplicación de inteligencia artificial y aprendizaje automático para crear nuevas herramientas de medición que ayuden a agilizar algunos de esos procesos subjetivos.

“Cuanto mejores sean las mediciones que tengamos de cosas que la mente humana no puede ver, mejores serán las preguntas de investigación, mejores los resultados y, en general, más rápido avanzará la comunidad”, añadió.

También está trabajando en un proyecto para desarrollar una evaluación psicológica que pueda identificar a los candidatos a agentes de policía que tienen menos probabilidades de presentar problemas de mala conducta. La investigación ha despertado su interés y espera, al finalizar su programa de cinco años, poder hacer la transición hacia una carrera de investigación académica.

“Creo que se necesita una cierta cantidad de creatividad para involucrarse en la investigación, para ver lo que ya ha sido publicado y descubrir qué falta. Es realmente satisfactorio ir encajando las piezas que faltan en el rompecabezas. “Es necesario resolver muchos problemas”, dijo. “Poder pensar en mi campo y proponer soluciones nuevas que nadie más haya pensado antes, es algo que creo que puede ser muy gratificante”.

Wyman is one of 60 doctoral students in the psychology program, which also includes clinical science, developmental psychology, and cognition, brain, and behavior, but that number is about to grow with the development of the Wilma and Peter Veldman Family Psychology Clinic.

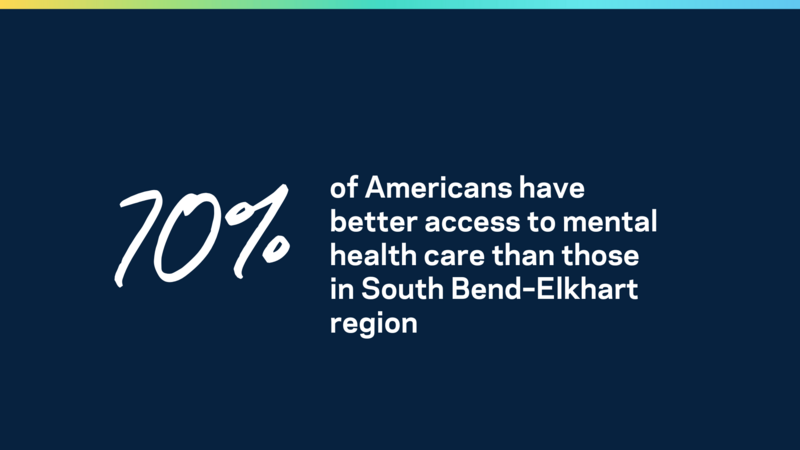

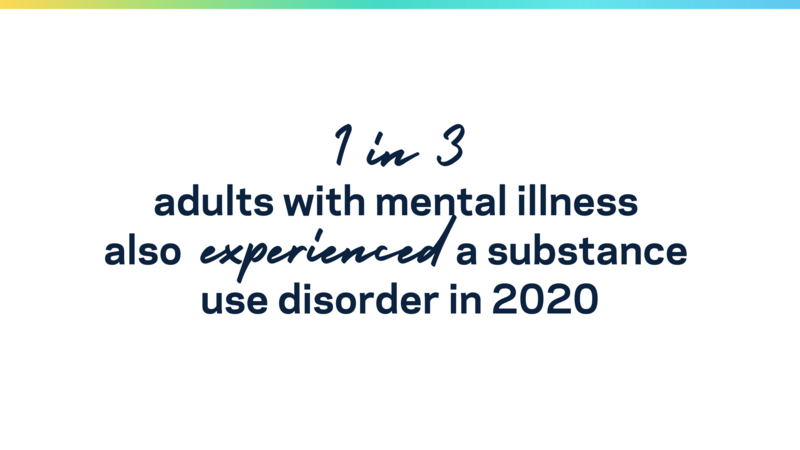

The new clinic, scheduled to open in 2026 in South Bend’s East Bank neighborhood, will bring together faculty experts focused on developing innovative methods for the prevention and treatment of mental health issues, and on informing the practice of clinical care across the nation. The new clinic will unite existing work at Notre Dame’s William J. Shaw Center for Children and Families with new research on substance use and other developing areas, and it will foster collaboration among experts focused on evidence-based treatments to mental health issues.

“Our approach at this clinic will involve looking at the whole human—considering a person in context, looking at their whole family and their whole life—and how we can treat not just that condition, but really their life in context and in the context of their community,” said Sarah Mustillo, the I.A. O’Shaughnessy Dean of the College of Arts and Letters.

Wyman es uno de los 60 estudiantes de doctorado en el programa de psicología, que también incluye Ciencias clínicas, Psicología del desarrollo y la cognición y Cerebro y comportamiento, pero ese número está a punto de crecer con el desarrollo de la Clínica de Psicología Familiar Wilma y Peter Veldman.

La nueva clínica, cuya apertura está prevista para 2026 en el barrio East Bank de South Bend, reunirá a profesores expertos centrados en el desarrollo de métodos innovadores para la prevención y el tratamiento de problemas de salud mental, y en informar la práctica clínica en todo el país. La nueva clínica unificará el trabajo existente en el Centro William J. Shaw para niños y familias de Notre Dame con nuevas investigaciones sobre el abuso de sustancias y otras áreas en desarrollo, y fomentará la colaboración entre expertos centrados en tratamientos basados en la evidencia para problemas de salud mental.

“Nuestro enfoque en esta clínica implicará considerar al ser humano en su totalidad, considerar a la persona en su contexto, observar a toda su familia y toda su vida, y cómo podemos tratar no solo esa condición, sino realmente su vida en su contexto y en el contexto de su comunidad”, anotó Sara Mustillo, Decana de la Facultad de Artes y Letras de I.A. O’Shaughnessy.

Sarah Mustillo, featured here, believes the new clinic will offer both research and service to improve the state of mental health care.

A key piece of the University’s Health and Well-Being Initiative, the clinic will increase the number of senior faculty in Notre Dame’s Department of Psychology, triple the number of clinical psychology graduate students, and triple the experiential learning opportunities for undergraduate psychology majors. It will also include the installation of a functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) machine, which will significantly enhance the University’s neuroscience research across campus.

The result will be a clinic that provides both research and service to offer a robust, comprehensive approach to mental care and support that will make a difference on campus, in the community, and beyond.

“At Notre Dame, we are challenged and empowered every day to use our research to be a force for good in the world,” Mustillo said. “I am forever grateful for the opportunity the Veldman Family Psychology Clinic presents to us to help heal a world deeply in need.”

La clínica, una pieza clave de la Iniciativa de Salud y Bienestar de la Universidad, aumentará el número de docentes titulares en el Departamento de Psicología de Notre Dame, triplicará el número de estudiantes de posgrado en psicología clínica y triplicará las oportunidades de aprendizaje experiencial para los estudiantes de pregrado en psicología. También incluirá la instalación de una máquina de resonancia magnética funcional (fMRI), que mejorará significativamente la investigación en neurociencia de la Universidad en todo el campus.

El resultado será una clínica de investigación y prestación de servicios que ofrezca un enfoque sólido e integral de atención y apoyo psicológico que marcará una diferencia en el campus, en la comunidad y más allá de estos.

“En Notre Dame, todos los días nos sentimos desafiados y empoderados a usar nuestra investigación como una fuerza para el bien en el mundo”, declaró Mustillo. “Estoy eternamente agradecido por la oportunidad que nos brinda la Clínica de Psicología Familiar Veldman de ayudar a sanar un mundo con necesidades profundas”.

What’s more, Mustillo sees the clinic’s reach extending far beyond South Bend, both by educating new clinicians and by disseminating evidence-based research.

“It will elevate the level of care across the community—not just the people that have access to our clinic, but the people that go to their local therapists,” she said. “We will provide training to the local therapists so they will have access to cutting-edge, evidence-based care that they might not have otherwise.”

Wyman echoed her sentiments. Notre Dame’s desire to share all that it learns, all that it creates, all that it has, is what brought him here in the first place.

“When I was looking for universities, what appealed most to me about Notre Dame was its Catholic mission. They are defined by the statement ‘here for each other and here for the world.’ Notre Dame had so many resources to support its own student body, but also was matched with the research and the passion to take the goodness that it created and give it to every corner of the world,” Wyman said. “I saw an opportunity to pursue mental health research that affected not just my peers, but also people in the corners of the earth that may not have access to mental health care.”

Es más, Mustillo prevé que el alcance de la clínica se extienda mucho más allá de South Bend, tanto educando a nuevos médicos como difundiendo investigaciones basadas en evidencia.

“Esto elevará el nivel de atención en toda la comunidad, no solo para las personas que tienen acceso a nuestra clínica, sino también para las personas que acuden a sus terapeutas locales”, afirmó. “Brindaremos capacitación a los terapeutas locales para que tengan acceso a una atención de vanguardia, basada en evidencia, a la que de otra manera no podrían acceder”.

Wyman hizo eco de sus opiniones. El deseo de Notre Dame de compartir todo lo que aprende, todo lo que crea, todo lo que tiene, es lo que lo trajo aquí en primer lugar.

“Cuando buscaba universidades, lo que más me atrajo de Notre Dame fue su misión católica. Se definen por el lema: "aquí estamos, el uno para el otro, y aquí estamos para el mundo". “Notre Dame tenía muchos recursos para apoyar a su propio cuerpo estudiantil, pero también contaba con la investigación y la pasión para tomar la bondad que creó y difundirla en todos los rincones del mundo”, sostuvo Wyman. “Vi una oportunidad de realizar una investigación sobre salud mental que tuviera un impacto no solo sobre mis compañeros, sino también en personas de todos los rincones del mundo que tal vez no tienen acceso a atención de salud mental”.

Credits

- Writer: Tara Hunt McMullen

- Photographers: Matt Cashore and Barbara Johnston

Créditos

Escritor: Tara Hunt McMullen

Fotos: Matt Cashore