Fighting to Protect the Brave

Diane Cotter knew cancer was a risk of her husband’s job. Paul had been a firefighter for 27 years, and they had been advised of not only the safety risks, but also the health implications from exposure to diesel exhaust and products of combustion. But when Paul, a 55-year-old in great shape, who ate healthy and took care of himself, received a prostate cancer diagnosis, Diane suspected something other than smoke was the culprit.

A hunch drew her to consider his gear — the protective clothing that had kept him safe as he rushed into burning buildings, saved lives and put out fires. As it turned out, that gear may have been a cause of his cancer.

Firefighter gear is complex — it has to be able to withstand both fire and water, and to resist extreme temperatures. The multiple layers — a thermal liner, a moisture barrier and an outer shell — must pass the National Fire Protection Association standards. Research had been done to study the gear and its textiles, but little existed about the chemical coatings on the gear that make it so effective.

Determined to learn more, Diane began digging. She emailed firefighters, activists, manufacturers. Many tried to shrug her off, but she was persistent. She pored over safety recalls, international regulations. Finally, she received a tip: Ask if the chemicals PFOA or PFOS are present in the gear.

Her research led her to believe that yes, chemicals known collectively as PFAS must be present in the gear, but manufacturers refused to provide information about the chemical content. And so she began looking for someone who could independently assess the clothing and give her an answer.

“What we didn't know was how much of these coatings were on the turnout gear and we didn’t have the chemical breakdown,” she says. “And we had no one to tell us what was in the coatings until we found Dr. Peaslee.”

Graham Peaslee

Graham Peaslee

Graham Peaslee is a professor of experimental nuclear physics at Notre Dame. Peaslee had devoted 20 years of his career to fundamental physics research and teaching, but in 2005 a lake near his home was found to be contaminated with chemicals from flame retardants. He began researching the prevalence of toxic chemicals and was thrust into a merger of science and policy, of chemicals and human health.

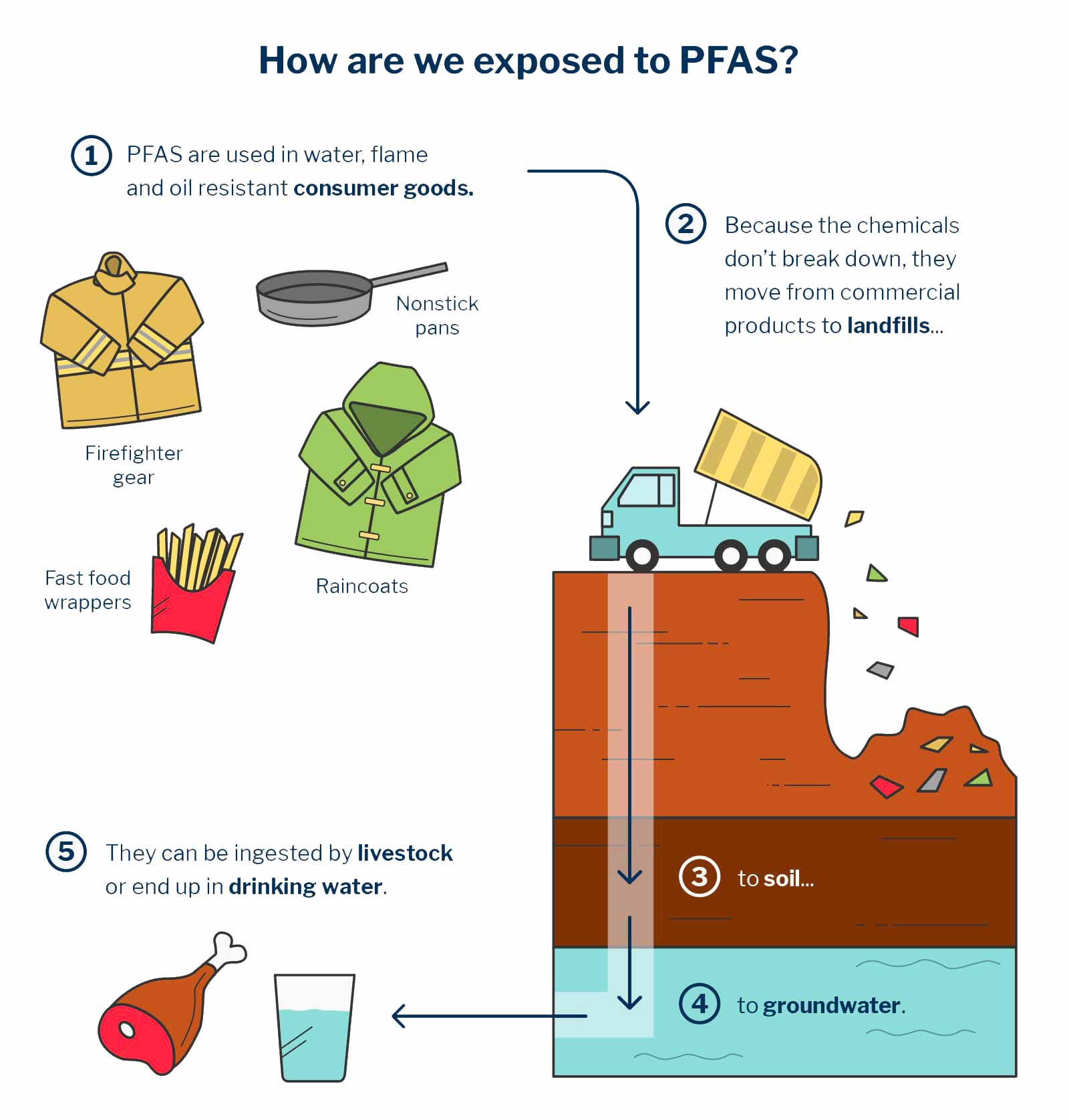

The experience tipped him off that harmful chemicals could be lurking in other unlikely places. He zeroed in on a class of fluorinated compounds, per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, referred to as PFAS, which have been linked to thyroid disease, hypertension, immunosuppression, low birthweight and kidney and testicular cancers.

“This is a really persistent class of chemicals,” says Peaslee. “It gets in the bloodstream; it stays there and can accumulate in the body. There are diseases that correlate with its presence, so we really don’t want this class of chemicals out there.”

Peaslee explains that these chemicals, also known as PFOA, PFOS or GenX, are particularly dangerous because they don’t break down. They move from commercial products to landfills to soil to groundwater. They can be ingested by livestock, or end up in drinking water, as was the case in Little Hocking, Ohio, a community downriver from a DuPont plant that leaked PFAS into soil and water for more than 50 years. Similar stories come from communities around military bases where firefighting foam laden with the compounds eventually made it into drinking water.

To identify markers of PFAS, scientists perform a complicated and lengthy chemical method. But Peaslee designed a novel technique that makes use of Notre Dame’s St. Andre particle accelerator.

He explains their development of what he calls a rapid spectroscopic technique. “This is where you use light to interact with matter to measure something. It can analyze 100 times faster than the chemical method for the same sort of detection,” he says. “In that sense it's a development that nobody else has been able to do, because nobody uses nuclear science to screen for this type of chemical. While it doesn’t replace them, it is considerably faster than the chemical approaches and can be used to screen for the fate and transport of these chemicals in the environment.”

His method got results in minutes, rather than hours, which allowed him to start testing many everyday items. Because PFAS are used in water, flame and oil resistance, they’re frequently used in consumer goods ranging from raincoats to nonstick pans to carpet to fast food wrappers. One of Peaslee’s studies discovered the presence of these chemicals in wrappers at 20 different fast food chains. Another study highlights cosmetics.

One result of these published studies is that consumer response has helped drive industries toward discontinuing use of the chemicals when it’s not necessary. Companies in the outerwear, furniture and food packaging industries are already making adjustments.

In the midst of his extensive testing for PFAS on products, Peaslee received a plea for help.

“I received an email from Diane, which was a heartfelt story about her husband's bout with cancer and that nobody would test her firefighting gear. I felt obliged to go and see if there was anything to her claims,” he says.

“The firefighters that Diane knew volunteered several sets of used and new gear from around the country, and we started getting dozens of sets of turnout gear delivered to our laboratory. When we looked at the gear, there was a remarkable consistency in how they were fabricated and the levels of fluorine that we were seeing in each of the layers of the gear. It was startling high,” he says. “There were perfluorinated compounds being used on the inside and the outside of this firefighting gear.”

Digging further into the issue, Peaslee began testing gear that was new, used, washed and unwashed, to help determine the extent of the issue. He wanted to educate firefighters about the potential hazards.

“Knowledge is empowerment,” he says. “These firefighters, men and women, are being exposed to something that they don’t know about. When they know about it they can mitigate the risks. They can treat the gear with respect and use it when they need it and then they can keep it separate from their lives when they don’t need it. For example, policies of where they keep the gear and where they store the gear might change, which is a pretty easy fix if it reduces your risk of exposure to the chemicals on the surface of the gear.”

Digging further into the issue, Peaslee began testing gear that was new, used, washed and unwashed, to help determine the extent of the issue. He wanted to educate firefighters about the potential hazards.

Digging further into the issue, Peaslee began testing gear that was new, used, washed and unwashed, to help determine the extent of the issue. He wanted to educate firefighters about the potential hazards.

In April, Peaslee shared his findings at the Fire Department Instructors Conference International, which had more than 35,000 attendees. The Cotters also continue to advocate for change for firefighters, now with Peaslee’s findings as backing for their cause.

Diane says, “What we know is that the chemical coatings have been used for at least 20 years. We never knew how much until Dr. Peaslee discovered, with his own specific testing methods, the amounts that are used. We've been told trace amounts, which, to us, is trying to minimize the issue, when in fact we really should be sounding the alarm on the issue.”

Now certain that there are toxic chemicals in the gear, Diane believes some manufacturers may have knowingly withheld that information. Peaslee was able to provide undeniable evidence that now needs to be addressed. Because of him, she says, the discussion has begun.

“Scientists have to learn to communicate when there's an issue like this, and not just do it in the safety of a laboratory.”

“[Dr. Peaslee] has embraced the fire service and the fire service has embraced him. And he is telling the truths of his findings in a way that makes sense to the fire service. He's approachable, he’s been letting everyone reach out to him and answers their questions,” she says.

Peaslee is quick to shrug off any praise and insists he’s doing what all scientists should.

He says, “Scientists have to learn to communicate when there's an issue like this, and not just do it in the safety of a laboratory. But to get out and talk to people about what may in fact impact them.”

“The reason I came to Notre Dame was that they had a facility that was different from what’s available anywhere else in the world. It has cutting-edge research facilities,” he says. “Their mission states that they are a university that wishes to give back to its community. I identify strongly with that mission.”

As research and awareness on PFAS has grown, so have efforts to reduce and eliminate their use. European firefighters are already moving away from PFAS in their gear.

In February, the EPA announced a maximum contaminant level for drinking water and also proposed enforcement tools for parties leaking PFAS into the environment.

In June, a bipartisan amendment passed that required the military to phase PFAS chemicals out of firefighting foam by 2023 — a response to alarming amounts of PFAS in contaminated drinking water at more than 175 military bases to date.

The state of Washington was the first to pass legislation to restrict the use of PFAS. In March 2018, the Healthy Food Packaging Act banned PFAS chemicals in paper food packaging. Another bill championed by the Washington State Council of Fire Fighters bans firefighting foams with added PFAS and requires gear containing the chemical to carry a warning. By 2020, the state will designate a list of other consumer products to remove PFAS.

Meanwhile, several corporations have independently gone PFAS-free. Whole Foods Market pulled takeout packaging that contained PFAS, and Kaiser Permanente, one of the largest health care providers in the U.S., and Google have banned the use of PFAS in finishes and materials it uses for building projects.

Today, Paul is cancer-free, but Diane isn’t willing to give up the fight to protect other firefighters.

“My husband leaving the fire department was probably the hardest thing we’ve had to endure. Even harder than the cancer, but we’re blessed because he’s survived it,” she says. “At this point in our lives, we’re fighting for change because it’s that important. We have family and friends, not just here in the United States, but across all the lands, across the planet, in Australia, Europe, Italy, who are asking the same questions. And Dr. Peaslee’s findings have an international impact.”

For questions regarding Professor Peaslee’s research, please contact him at gpeaslee@nd.edu.