Fighting to Prevent Homelessness

In the spring of 2020, Faron Brinkley moved to Chicago to take a job with a hotel chain. Two weeks into his training, COVID-19 hit the city, halting the hospitality industry. In a new city with no paying job, no apartment and little savings, Brinkley stayed with a friend and then in a car, and faced the possibility of homelessness.

“I didn’t know because of COVID how everything was going to end up as far as needing a place to stay,” recalls Brinkley, who spent his childhood in foster care and is learning to live independently.

In the spring of 2020, Faron Brinkley moved to Chicago to take a job with a hotel chain. Two weeks into his training, COVID-19 hit the city, halting the hospitality industry.

In the spring of 2020, Faron Brinkley moved to Chicago to take a job with a hotel chain. Two weeks into his training, COVID-19 hit the city, halting the hospitality industry.

Brinkley stayed with a friend and then in a car, and faced the possibility of homelessness.

Brinkley stayed with a friend and then in a car, and faced the possibility of homelessness.

A case worker recommended that he request short-term assistance by calling 311, the Homeless Prevention Call Center for the City of Chicago, currently run by Catholic Charities of Chicago. The center conducts telephone assessments and connects eligible callers with community resources and prevention agencies. According to Tracey Blackburn, supervisor for the call center, operators typically answer around 700 calls each week, though the number has ballooned during the COVID outbreak. The center focuses on individuals and families who are on the brink of homelessness due to unforeseen circumstances such as illness, injury or sudden unemployment. Because they still have housing, they can perhaps avoid losing their homes if given a small, one-time payment.

To date, the program has helped thousands of families stay off the streets, but Catholic Charities of Chicago knew funding for public programs is never guaranteed, so it wanted to prove its method was cost effective and impactful. In 2012 it approached Notre Dame’s Wilson Sheehan Lab for Economic Opportunities (LEO) for assistance. The problem, the charity explained, is that the success of call centers is often measured by the number of calls, rather than the number of people successfully kept in their homes. Could LEO researchers measure the call center’s effectiveness rather than volume?

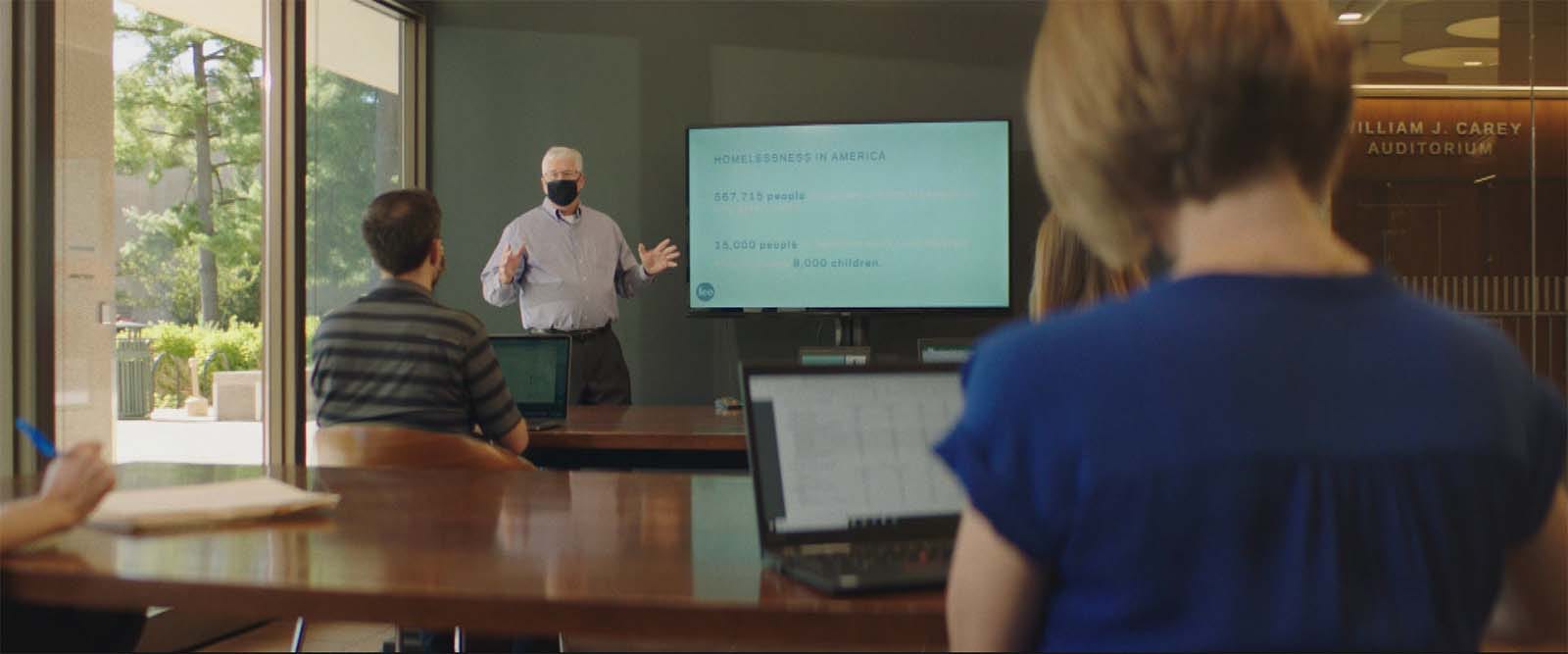

Bill Evans, the Keough-Hesburgh Professor of Economics and LEO co-founder, was curious if the small amounts of emergency funding were enough to keep people out of shelters or if it was just delaying inevitable homelessness.

Bill Evans, the Keough-Hesburgh Professor of Economics and LEO co-founder, was curious if the small amounts of emergency funding were enough to keep people out of shelters or if it was just delaying inevitable homelessness.

Bill Evans, the Keough-Hesburgh Professor of Economics and LEO co-founder, was curious if the small amounts of emergency funding were enough to keep people out of shelters or if it was just delaying inevitable homelessness.“From the initial conversation we had with Catholic Charities, we knew there was going to be a good project here,” Evans says. “It was just a question of getting access to the data, and Catholic Charities’ ties to the community there, especially in the homelessness network, really made this project work.

“What we were able to do is follow people for an extended period of time after they made their phone call. We knew whether they were offered financial assistance or not. And then we just track whether they end up showing up in the homeless system,” Evans explains. “There was a fairly substantial decline in the probability that family ends up homeless as a result of receiving emergency financial assistance — about a 76 percent decline in that probability — so the program seems to be very effective.”

“What we learned is that emergency financial assistance doesn’t simply kick the can down the road. It helps people overcome a crisis and stay in their homes long-term.”

In addition to the more than 70 percent decline in homelessness, the program also had kept over 600 children from living on the streets.

“What we learned is that emergency financial assistance doesn’t simply kick the can down the road,” Evans says. “It helps people overcome a crisis and stay in their homes long-term.”

Lisa Morrison Butler, Chicago’s commissioner of the Department of Family and Support Services, says data like what Notre Dame provided is critical to making educated decisions, rather than gut instincts, about funding the most cost-effective options.

“There are 300,000 vulnerable Chicagoans at any given moment in time. Their needs are varied and as diverse as they are. And it often feels like there is not enough money to wrap them all in everything they need. And so it is absolutely necessary that we be able to ensure that every dollar we are spending is doing a dollar’s worth of work, that nothing is being targeted to the wrong people, to the wrong program or to the wrong intervention. We have got to ensure ourselves, those vulnerable residents and taxpayers that every single dollar we spend is working as hard as it can,” she says.

“Notre Dame’s research has allowed us to be way more proactive in defining, targeting and funding solutions. And it’s also allowed us to understand gaps that we have in our current menu of programs and services,” she continues.

In addition to the more than 70 percent decline in homelessness, the program also had kept over 600 children from living on the streets.

In addition to the more than 70 percent decline in homelessness, the program also had kept over 600 children from living on the streets.Now, states like California are looking at this evidence to redesign their strategies for homelessness prevention.

In Chicago, since the research was published, the call center has fielded more than 400,000 calls and referred more than 70,000 of those callers for assistance.

Morrison Butler adds, “Partnering with an academic institution like Notre Dame is the perfect complement to the skill set of our team here. We’ve got folks working in our homeless services division that have been working on that issue for 20 or 30 years, and they are very skilled and very passionate, but the skills that the Notre Dame team can bring to the table are different than our own. And so that complimentary sweet spot, where our traditional strength meets their academic and research skills, that’s just a very special combination. And in this case has really helped us get better data so that we can do better work and more impactful work for the vulnerable Chicagoans as we seek to serve.”

In Brinkley’s case, he was awarded emergency funding to help him pay the first month’s rent and security deposit.

“That was the best call of my life,” he says. “I would have definitely been homeless because I knew people here, but they were also in a situation where they didn’t know what their incomes were going to look like.”

Brinkley was awarded emergency funding to help him pay the first month's rent and security deposit. He is now employed and taking classes toward his degree in psychology.

Brinkley was awarded emergency funding to help him pay the first month's rent and security deposit. He is now employed and taking classes toward his degree in psychology.Catholic Charities also helped him apply for unemployment while he looked for a new job. Brinkley’s now employed and taking classes toward his degree in psychology. He is a published author and hopes to take what he has learned to create a program for young adults like himself who grew up in the foster care system.

“Homelessness is the biggest thing that foster children deal with when they age out of foster care,” he explains. “They’re not equipped to live on their own because they haven’t been taught to pay bills, manage finances or even fill out a resume. I want to be able to create something for them because I know how hard it was for me.”