Fighting for Resilient Communities

Nikos and Zeta Giannopoulos grew up in Mati, Greece, an idyllic seaside town that draws both tourists and locals with the allure of fresh, salty air; cool blue waters; and a serene canopy of lush pines. Mati is where the couple fell in love, had a community of friends and neighbors, raised their children, and felt their everyday life was paradise.

But on July 23, 2018, at 5 p.m., helicopters began flying overhead, signaling something was amiss. Soon after, smoke began trickling in from the west, but information was sparse. Some reports said a wildfire was still far away, others said it had changed direction and was headed to town, Nikos recalls. Confusion ensued.

Mati, Greece is an idyllic seaside town that draws both tourists and locals with the allure of fresh, salty air; cool blue waters; and a serene canopy of lush pines.

Mati, Greece is an idyllic seaside town that draws both tourists and locals with the allure of fresh, salty air; cool blue waters; and a serene canopy of lush pines.

Mati in the wake of the July 23, 2018 fire.

Mati in the wake of the July 23, 2018 fire.

By 6 p.m. the house was on fire. Zeta loaded the dog into the car and began driving. She was fortunate, she says — she guessed and chose the right direction to travel. Because of the conflicting information being shared, some people drove straight into the fire and died. Smoke filled the town to the point it was impossible to see, Zeta recalls.

“It was coming after me, and I was shouting ‘Where are you? Where are you?’ He [Nikos] told me, ‘Don’t shout, I’m here.’ I could not see him,” Zeta remembers.

“I was 5 meters behind,” Nikos adds.

People attempted to move toward safety. Many fled toward the sea, but some couldn’t find the entrance along the seawall. Others tried to drive out of town or wait in their homes. Nikos and Zeta survived, but 102 people did not, among them Nikos’ mother. Neither did their home, their possessions, or the photos of the life they had built. What was once a paradise lay in ruin and ash.

Mati in the wake of the July 23, 2018 fire. Photo by Vassilis Vrettos. A publication of his full collection, Βασίλης Βρεττός 23.7.2018, is available for purchase.

Mati in the wake of the July 23, 2018 fire. Photo by Vassilis Vrettos. A publication of his full collection, Βασίλης Βρεττός 23.7.2018, is available for purchase.

Mati in the wake of the July 23, 2018 fire. Photo by Vassilis Vrettos. A publication of his full collection, Βασίλης Βρεττός 23.7.2018, is available for purchase.

Mati in the wake of the July 23, 2018 fire. Photo by Vassilis Vrettos. A publication of his full collection, Βασίλης Βρεττός 23.7.2018, is available for purchase.

Michael Lykoudis, a Notre Dame professor of architecture, is the son of Greek immigrants who ventured to the States on Fulbright scholarships. Though they eventually settled near Purdue where his dad pursued aeronautical engineering, Lykoudis spent most of his summers back in Greece with his grandparents. Even today, he maintains the tradition with his own home in Athens.

“When the fire in Mati occurred, of course we were all just overwhelmed,” he says. “Nothing of this magnitude happens in Greece very often.”

He was contemplating what he could do to help and had opened discussions with colleagues and professionals in Greece when he received a call from INTBAU, an architecture charity founded by HRH The Prince of Wales. HRH established INTBAU to be a global champion of local, traditional, sustainable architecture, which is Lykoudis’ specialty. Prince Charles, who like Lykoudis has roots in and family ties to Greece, was devastated by news of the fires, and wanted to do something to help the Mati community to rebuild. The desire to help was put into action by Lykoudis, who began outlining plans with INTBAU for what he and Notre Dame’s School of Architecture would do to support redesign efforts for Mati.

Michael Lykoudis (center) gathered nine fifth-year architecture students to undertake appraisal and redesign efforts of Mati.

Michael Lykoudis (center) gathered nine fifth-year architecture students to undertake appraisal and redesign efforts of Mati.

Moved by the devastation and motivated by confidence from the prince’s foundation, Lykoudis gathered nine fifth-year students to undertake appraisal and redesign. In the summer of 2019, and again in the fall, the group traveled to Mati to assess the damage and determine how to improve the town’s resiliency in the face of future emergencies, while keeping its beauty and traditional architecture. While the first visit focused on gathering information, the second allowed for personal connections with the city’s survivors, Lykoudis explains.

“I think it was a good way to do it because we just needed to get the raw data of what the site was … and the second time in October, the humanity of it all came out. At that point the switch flipped and, you know, I think if any students thought that they had any reservations about what the project was about, that was quickly changed after the second visit,” Lykoudis says. “You need both. You need to have a dispassionate understanding of what the conditions are and then you also just have to have the experience. It will give you the empathy to get inside the hearts and minds of the people there.”

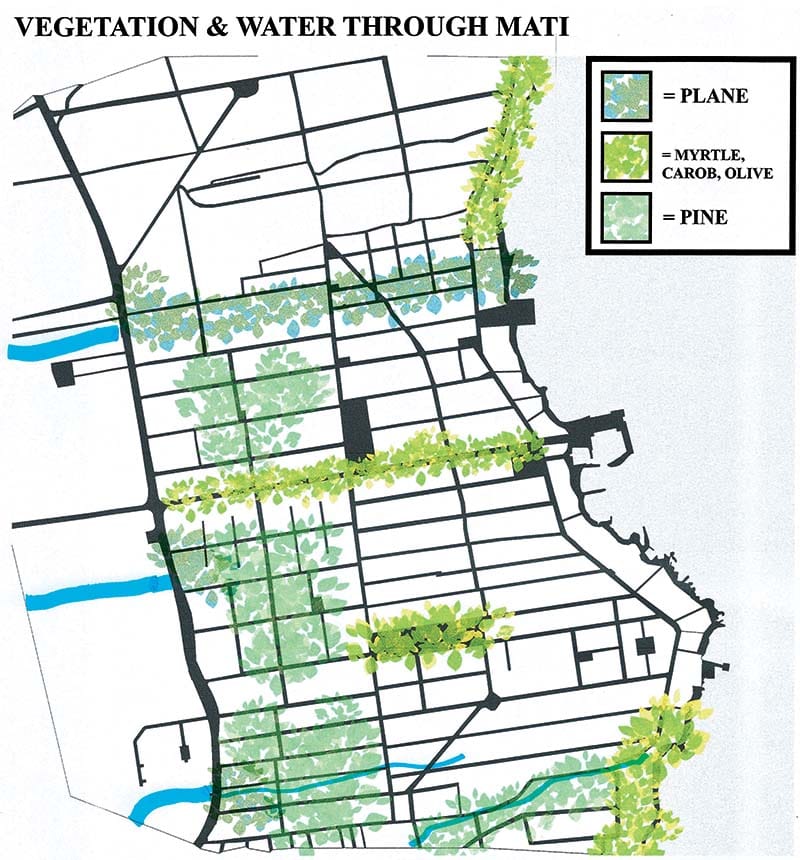

Working with a botanist, the students determined the flammable pine trees should be interspersed with myrtle, olive and carob trees, all of which have a reduced fire risk and are resilient to the effects of climate change.

Working with a botanist, the students determined the flammable pine trees should be interspersed with myrtle, olive and carob trees, all of which have a reduced fire risk and are resilient to the effects of climate change.

The experience was emotionally charged for many of the students. William Marsh ’20 was among the architecture students and compared the devastation to his visits to New Orleans during the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina.

“The land itself was still scarred. Buildings were mangled and left uninhabitable. Tree stumps were still yet to be rooted out, and very few places looked like what Mati had been before the fire,” he recalls. “The devastation gave us a sense of urgency in the back of our minds. We always had the sense that the people of Mati had their lives torn from them and we needed to restore it as best as we could, as quickly as we could.”

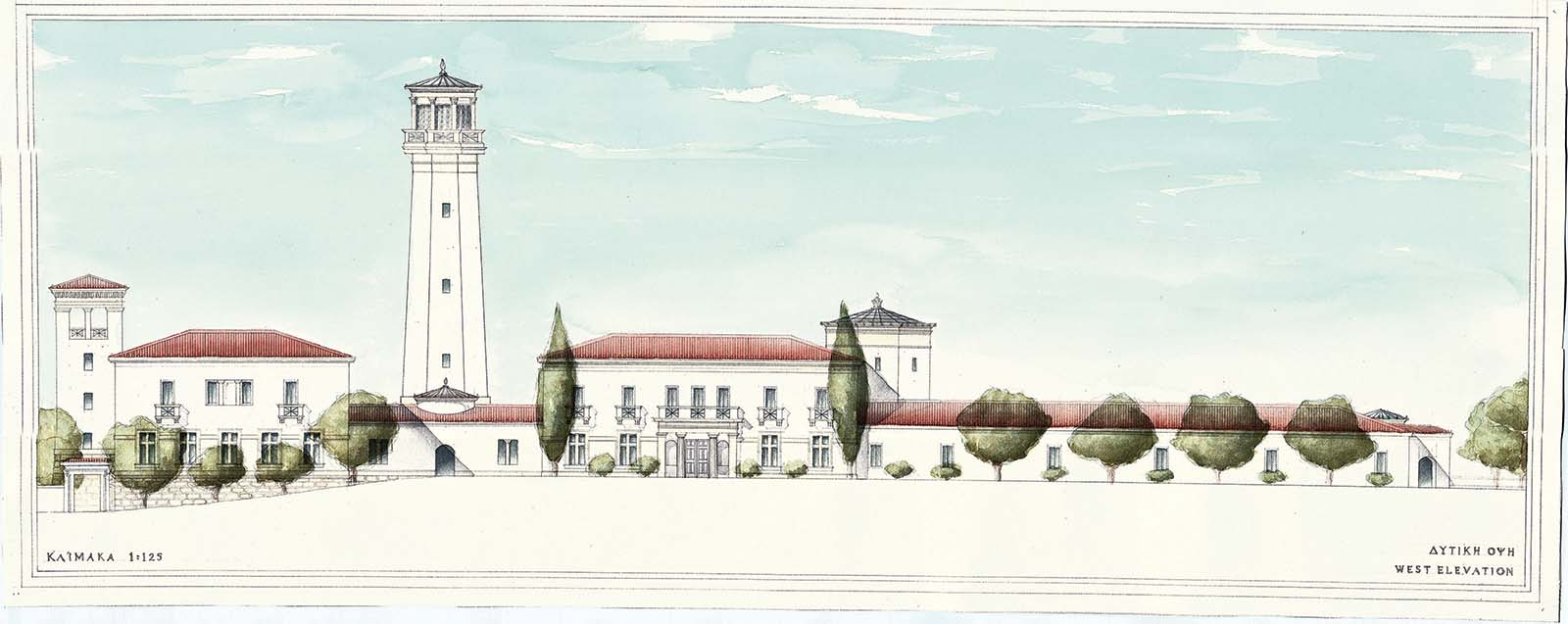

The result of the trips was impressive architecture work. The students determined some of the priorities included a fire defense perimeter, enhanced access to the beach with lighting, new fire alert and fighting systems, bells and a tall clock tower to point people to safety in reduced visibility, and new streets to prevent traffic jams. They also believed that while they could and should recreate Mati’s lush canopy, with the help of a botanist, they determined the flammable pine trees should be interspersed with myrtle, olive and carob trees, all of which have a reduced fire risk and are resilient to the effects of climate change.

“There’s no silver bullet, but everything could give one more layer of safety,” Lykoudis says, noting the many thoughtful details incorporated in the designs to improve safety and resilience.

While tragic, the fire and the ensuing redesign was an opportune time to consider the changing climate’s impact on Mati, Lykoudis says. Wildfires, rising sea levels and environmental degradation may all eventually impact the coastal region, and this rebuild allows the town to prepare. But planning for issues and vulnerabilities resulting from climate change is essential for towns beyond Mati. Today, as deadly fires burn millions of acres across the western United States, American communities will also need to make changes in order to prevent future dangers.

“I was moved to assist the people of Mati in their time of need, but recent events have shown us that wildfires are an increasing threat to people around the world from Australia to California and beyond,” Lykoudis says. “In addition to taking action to mitigate the effects of climate change, we should reimagine vulnerable communities in ways that both enhance quality of life for the community and increase the fire resilience of the built environment.”

Fortunately, Lykoudis notes, it doesn’t require drastic change, just a return to traditional roots and to understanding and working with nature rather than against it.

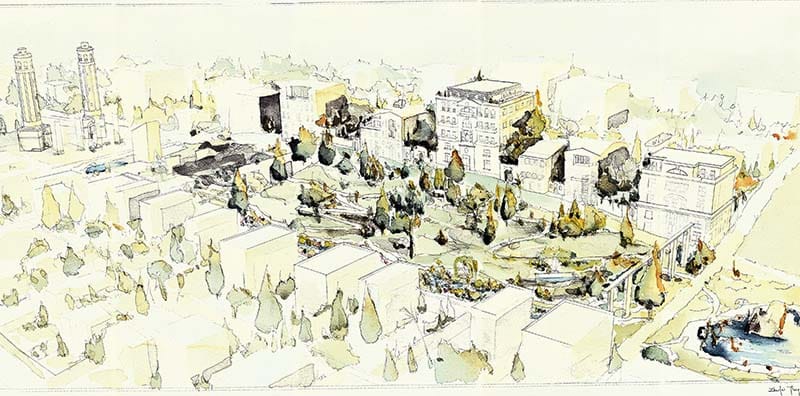

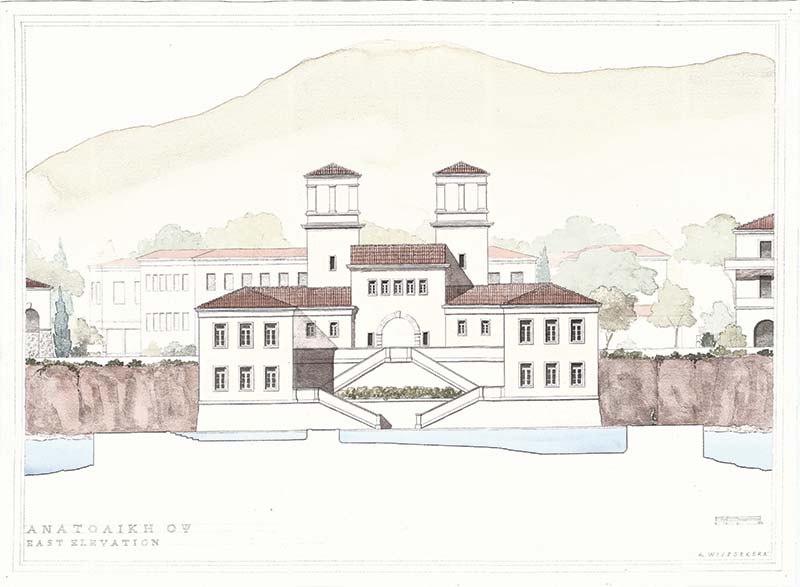

The group designed a 75-year master plan, including student sketches for a fire station, a town hall and bell tower, hotels, vineyards, public pools and parks, and apartment buildings, all designed in a range of vernacular Greek styles.

The Hotel by Austin Proehl.

The Hotel by Austin Proehl.

The Apartment buildings by Zhuofei Tang.

The Apartment buildings by Zhuofei Tang.

The Public Pool by Amali Wijesekera.

The Public Pool by Amali Wijesekera.

Giorgos Stasinos, president of the Technical Chamber of Greece, says, “The participation of Notre Dame is very important for us because the students have a lot of new ideas about how you can build a new area like Mati, because they have different options from other countries, other cities, and they can help bring us new ideas.”

Lykoudis recently presented the work to the residents of Mati, and now hopes to return in 2021 to develop a plan alongside residents and professionals.

Prince Charles has also stayed abreast of the situation. In an opinion piece published in the Greek daily newspaper Ta Nea in July, he wrote:

“I am, of course, acutely aware of the fact that the COVID-19 crisis is not the only difficulty Greece has faced in recent years. Indeed, my wife and I were both deeply saddened when we heard the news of the devastating fires which raged in Attica shortly after our visit in 2018. The tragic loss of life and distressing aftermath caused by these fires compelled me to offer some assistance, however small, to help the region take its first steps towards rebuilding.

“To this end, my Charitable Fund helped to provide the necessary financial assistance for a group of universities and practitioners to help in the creation of an aspirational masterplan for Mati which they hope to share with the local community later this year.

“This is, in essence, a collection of plans and drawings which shows how rebuilding, now and into the future, could create a place that is resilient and that demonstrates some of the many wonderful qualities of traditional Greek architecture and urbanism. Their conceptual masterplan for Mati focuses in particular on fire resistance, the coastline, public and green spaces, and rainfall capture through a sustainable urban drainage system.

“Leading on this work was a team from the University of Notre Dame School of Architecture under the supervision of the School’s Dean, Michael Lykoudis, in collaboration with partners including the National Technical University of Athens, the University of Patras and, crucially, the local community.”

Even with the delayed timeline, what remains firm is that in spite of fire, tragedy and pandemic, Mati will rebuild.

Mati resident Laila De Messi acknowledged that these days, much of the town is still in rough shape. But she said the community will come together to recreate their home.

“We love this place. The fire didn’t send us away. It made us stay here and try to rebuild it,” she says. “I believe that Mati will be again as it was, not with such big trees, but green, and the houses will be made again. Slowly, but they will made again.”

Header photo: Mati in the wake of the July 23, 2018 fire. Photo by Vassilis Vrettos. A publication of his full collection, Βασίλης Βρεττός 23.7.2018, is available for purchase.