Fighting for Compassion in Medicine

Sam Grewe ’21 was 13 when he was diagnosed with osteosarcoma, a rare type of bone cancer that eventually required his right leg to be amputated. While his peers muddled through middle school, he bounced between doctor’s appointments, chemotherapy, surgeries and therapy. But good doctors, Grewe insists, facilitated dramatic results in his recovery.

Sam Grewe ’21 was 13 when he was diagnosed with osteosarcoma, a rare type of bone cancer that eventually required his right leg to be amputated.

Sam Grewe ’21 was 13 when he was diagnosed with osteosarcoma, a rare type of bone cancer that eventually required his right leg to be amputated.

“I was a patient for two years of my life and I know what a good doctor looks like, and I know what a bad doctor looks like,” he says, noting what a positive impact his oncologist had on his recovery. “She didn’t treat me like a series of statistics and numbers and lab counts. She sat down and told us what her plan was in English terms we could understand at the time ... including what was possible to happen, good or bad. I think the degree of communication was the biggest thing because it gave us comfort knowing that there was no information being withheld.”

That level of communication gave him agency in his decisions and his recovery, he said, even as a young teen. It motivated him to work hard. Then his doctor went on leave and he was temporarily assigned to someone new. Immediately, he saw a downshift in his progress.

“Then I realized the effect that the patient-doctor relationship can have on outcome,” he says.

Dominic Vachon has also experienced the importance of patient-doctor relationships. In 1995 Vachon was a practicing psychologist, counseling health care providers worn thin by day after day of patient care. In time, Vachon, too, became burnt out. To survive, he emotionally detached from his patients but still harbored a growing burden. He wasn’t alone — more than 50 percent of physicians have symptoms of burnout, and the impact is seen on both the physicians and their patients. The antidote, Vachon believed, was a better understanding of compassion in caregivers. But he needed the science to prove it.

“There is a crisis of compassion in health care,” says Vachon. “Compassion is essential for patient care and it’s essential for the well-being of the clinician. The two go hand in hand.”

Compassion, Vachon is quick to note, is more than kindness and cheerful bedside demeanor. It has four distinct components: You have to notice suffering, be moved by it, want to do something about it, and act capably.

Dominic Vachon, the John G. Sheedy, M.D., Director of Notre Dame’s Ruth M. Hillebrand Center for Compassionate Care in Medicine, focuses his research on the relationship between empathy and burnout.

Dominic Vachon, the John G. Sheedy, M.D., Director of Notre Dame’s Ruth M. Hillebrand Center for Compassionate Care in Medicine, focuses his research on the relationship between empathy and burnout.

“Compassion is more than your feelings. Compassion is your motivation to apply your competence to that patient in front of you. Compassion is what drives you to be as competent as you can be,” he explains. “When you think that compassion is only about being sympathetic and warm and good bedside manner, those are all true, but what the science of compassion really helps reveal to us is that it’s not just your emotions. It’s actually how you manage your emotions, how you’re motivated to respond to the suffering in front of you. And how you can bring to bear all your competence right in front of you.”

Vachon is now the John G. Sheedy, M.D., Director of Notre Dame’s Ruth M. Hillebrand Center for Compassionate Care in Medicine. His research has largely focused on applying the science of compassion to clinical practice and clinician self-care, a growing field of study that employs advances in biology, neuroscience and psychology to help better educate and equip doctors to withstand the trials of the job.

The center was founded in 2011, thanks to a gift from the late Ruth M. Hillebrand, a clinical psychologist who was given a terminal cancer diagnosis over the phone late at night by a physician. He then promptly hung up. Before her death, she asked her brother, Joseph Hillebrand ’43, to use the gift to help train physicians in compassionate care and communication. He helped establish Notre Dame’s center and another at the University of Toledo Medical School. Before his own death, he noted, “Many doctors appear to be scientists before compassionate human beings, so my sister thought they needed to be trained to compassionately communicate with patients.”

“Compassion is more than your feelings. Compassion is your motivation to apply your competence to that patient in front of you. Compassion is what drives you to be as competent as you can be.”

Since the center’s founding, nearly 1,000 undergraduates have taken courses such as patient-centered medicine, medical counseling and science of compassion. Students can also now opt in to a 15-credit minor titled “compassionate care in medicine,” or to community-based learning opportunities with local partners through the Center for Social Concerns. And while the students are still undergraduates — the only undergraduates in the country receiving this kind of preparation — Vachon insists that doing this before the highly stressed period of medical school makes it a great time to teach these lessons.

“It’s hard to learn this compassion piece,” he says. “The thinking is, why don’t we just start now? Why don’t we plant the tree earlier so it has more likelihood of thriving?”

To Dr. Brian Donley ’86, CEO of Cleveland Clinic London, that timing is critical. Drawing from his background in orthopedics, he compares compassion to a muscle. He says the more you exercise it, the stronger it gets. So if students can learn empathetic practice at the undergraduate level, they can then put it to use during medical school, during residency, and as attendings, all of which will make them better caregivers.

“Compassion is a skill that can be learned. It’s not you have it or don’t have it,” Donley says. “The fact that Dominic is teaching this, and Notre Dame is one of the few if not only places in the country where this is happening, is a massive step forward to help improve our health care system.”

Donley has gotten involved, too. Last year he taught a course titled Healthcare: the Business of Empathy to Notre Dame undergraduates studying in London. He mentions that medical schools are getting on board with this field, but he hopes to see compassion taught earlier in the student curricula, and perhaps even make its way onto the MCAT to motivate students to buy in.

Donley, meanwhile, is designing a new hospital in London. While the number of beds, the quality of the care and the volume of patients served is important, he insists the focus of this new system is instilling empathy — both in and for all workers, from the janitors, to the accountants, to the nurses and surgeons. In his estimation, if all employees feel valued, they will in turn improve the patient experience.

Since the center’s founding, nearly 1,000 undergraduates have taken courses designed to teach skills such as personalism, medical counseling and clinical ethics.

Since the center’s founding, nearly 1,000 undergraduates have taken courses designed to teach skills such as personalism, medical counseling and clinical ethics.

“Empathy has to be designed into every aspect of health care,” he says. “When you’re designing a health care system, you have to equally place empathy as a focus for your caregivers, because they are the ones that will deliver empathy.”

The importance of empathy is on display in the chaos of the COVID-19 pandemic, he says. While health care workers are experiencing fear, stress and exhaustion, their work is being vocally praised and appreciated. It’s a small silver lining, he says, that the pandemic has made clear the value of health care workers and the importance of caring for them as they care for others.

It has also presented new, interesting examples for the students to observe, Vachon says. With a cohort of around 20 physicians and nurses who guest teach in the program, students must consider questions like how do you make a patient feel heard and safe during telehealth appointments? How do clinicians hang in there when the situation is bleak? And how, and why, should practitioners practice self-care in the midst of such suffering?

“This is what we were built for,” Vachon says of the center. “What we’ve been studying turns out to be absolutely the core of it. And we’re seeing [compassion] demonstrated every single day right now throughout the world.”

During Grewe’s cancer treatments at South Bend Memorial Hospital, he received an invitation to become an honorary member of the 2012 Notre Dame football team and get full access to the sideline, locker room and events. Players visited him during treatments and adopted him as part of the team. In the flurry and excitement of that undefeated season, Grewe found the motivation to push himself.

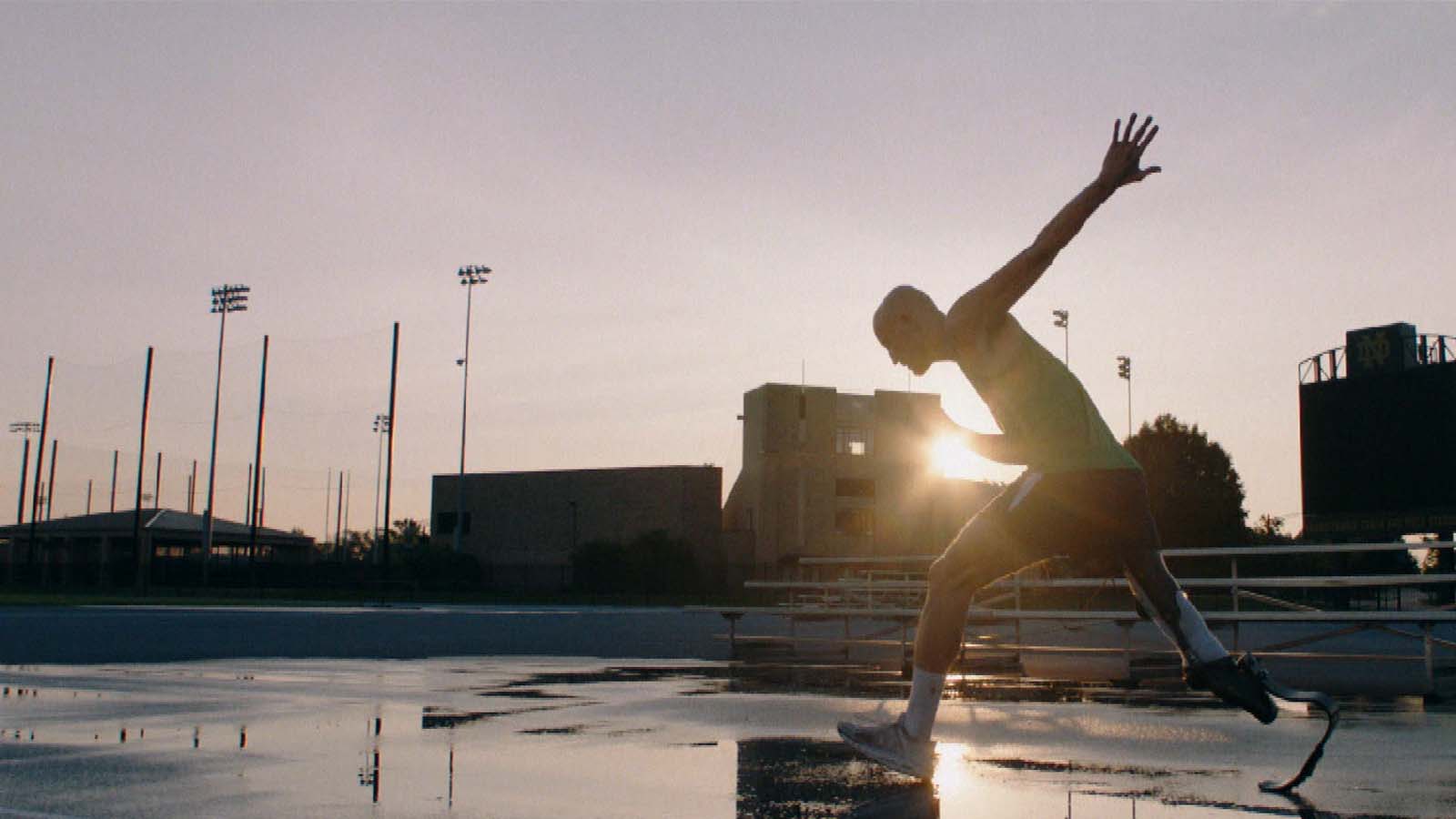

He was able to start high school with his peers, but had to catch up, both physically and academically, after spending two years in the hospital. Slowly, he learned to walk with a prosthetic, then made the basketball team, the football team and the lacrosse team. Though he was making remarkable progress, he was discouraged because he wasn’t playing at the same level as before his surgery, so his dad recommended adaptive sports. With the Great Lakes Adaptive Sports Association, he tried his hand at track and field. Immediately, high jump caught his attention.

“The cool thing about it was it gave me the ability to jump off of my one good leg and didn’t necessarily emphasize or rely on my other leg, which I was still learning how to use,” he explains.

Grewe walked on to the Notre Dame track team, where he is now a senior and a medical school hopeful.

Grewe walked on to the Notre Dame track team, where he is now a senior and a medical school hopeful.

After just a year of training, Grewe used his natural athleticism and his good leg to propel him to shocking heights, winning the world championships in Doha, Qatar. He then added a silver medal from the Paralympic Rio Games in 2016 and two more gold world championships. He’s since been training for the Tokyo games and walked on to the Notre Dame track team, where he’s now a senior and a medical school hopeful.

“It really just seemed like it was almost my obligation to give back because I was the recipient of so much care and many good doctors. I suppose if I have the opportunity to do the same, that’s something I should pursue,” he says.

As he eyes a career in oncology or orthopedics, Grewe is making sure to arm himself with lessons from the Hillebrand program. He’s currently enrolled in Vachon’s Compassionate Care in Medicine class and the Introduction to Clinical Ethics course.

Music: “Believe” performed by Meek Mill feat. Justin Timberlake. Courtesy of Maybach Music Group, LLC. / Atlantic Recording Corp.

Photo: Courtesy of the Grewe Family.