Fighting to Understand the Scientific Impact of Community

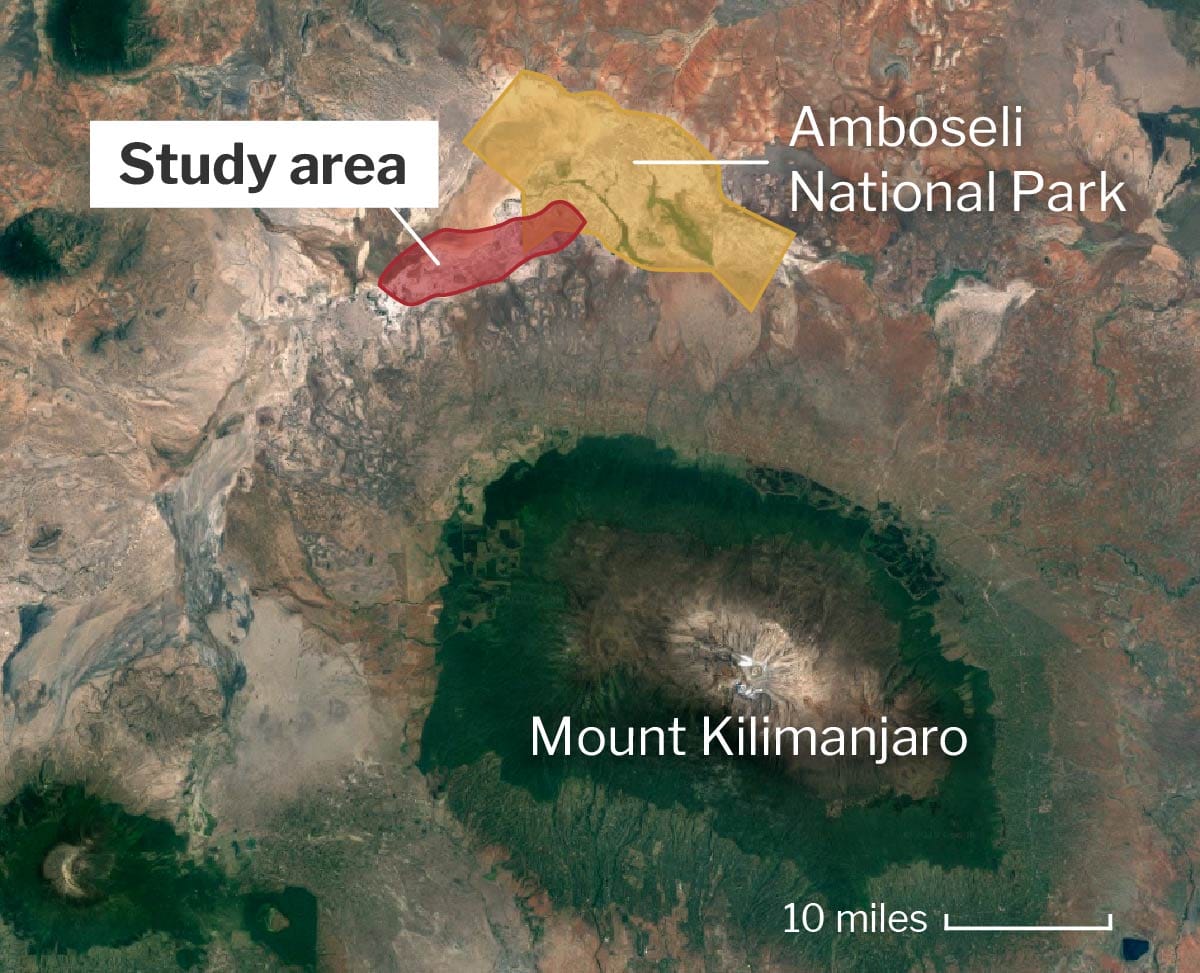

Playing in the shadow of Mount Kilimanjaro are 300 baboons that are the focus of one of the longest-running studies of wild primates. For more than 40 years, these Amboseli baboons and their ancestors have provided important data about questions in evolution, genetics, nutrition, hybridization and parasitology.

Beth Archie, Associate Professor of Biology at Notre Dame, stands on a dusty plain in southeastern Kenya watching the baboons, jotting notes on their social interactions and gathering their droppings. Back home, her notes and those of her colleagues will help answer the study’s overarching question: Why be social?

Beth Archie

Beth Archie

Archie's study area is in the shadow of Mount Kilimanjaro.

Archie's study area is in the shadow of Mount Kilimanjaro.

“It’s been a longstanding puzzle in humans. We know in people that people who have strong social relationships tend to lead longer lives and lead healthier lives. Figuring out why that is true is a big puzzle. It’s also really hard to do in people for a number of reasons,“ she says, detailing issues like humans’ longer lifespans, being able to accurately track a human’s social behavior, and needing access to fecal samples. But the baboons make for far more cooperative subjects, she says. And because the Amboseli baboons share a 94 percent genetic similarity to humans, it’s but a small jump from conclusions about the primates to humans.

Archie’s lab focuses on the interaction between social behavior and health and survival. How, Archie wonders, can a baboon’s social life impact things like lifespan, parasite risk, fertility and gut microbiomes? In short, why does being social make you healthier?

“This is a place where we can make a contribution that is useful to human health but which would be really hard to accomplish in studying humans,“ she says.

“This is a place where we can make a contribution that is useful to human health but which would be really hard to accomplish in studying humans.”

The study dates back to 1963 when Jeanne and Stuart Altmann, then researchers at the University of Chicago, were traveling East Africa in search of a location for a baboon study. They set up a 13-month study in what is now the Amboseli National Park, and then returned in 1971 with the idea for a permanent project, which is still running today. In 1984, Susan Alberts, now with Duke University, joined the Amboseli Baboon Project, and in 2010 added two of her postdocs, Archie and Duke’s Jenny Tung, as associate directors.

The researchers visit periodically throughout the year, but they rely on an experienced field team that lives in Amboseli National Park and studies the baboons six days a week, 52 weeks of the year, for much of their information. Raphael Mututua, the senior field assistant, has been on the project since 1981. He and the other assistants detail everything from fights to friendships, pregnancies to deaths. They share these assessments via email and Skype, and also regularly collect stool samples for analysis.

Those samples are key for Archie, who is keen to better understand the baboons’ gut biomes. Thanks to a 15-year collection of 20,000 baboon droppings, she has proven that baboons in the same social group have similar gut biomes — the combination of good and bad bacteria that help resist disease, mediate toxins in food, make vitamins and help digestion. Now she’s studying whether these biomes change in sync in a community or individually. The answer could dictate how to best design gut therapies for humans.

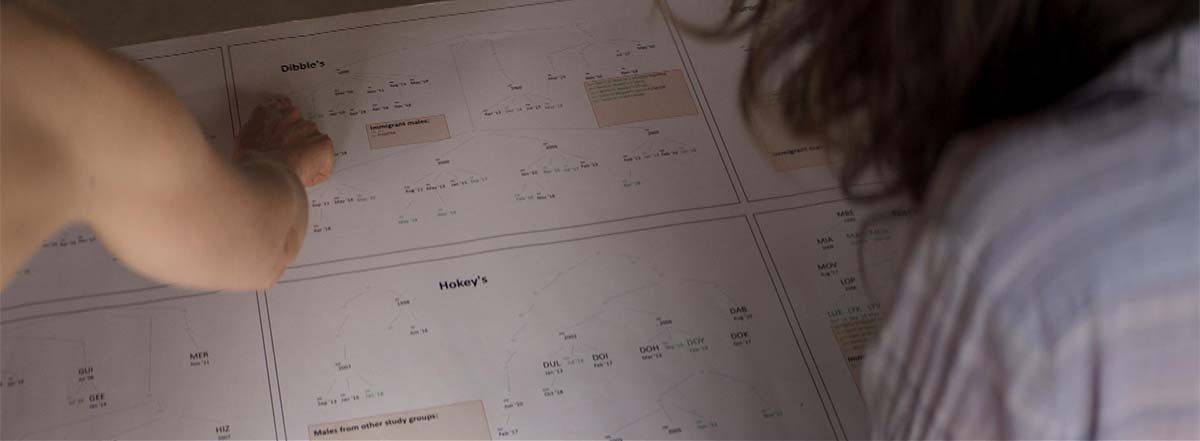

Archie (left) stands on a dusty plain in southeastern Kenya watching the baboons, jotting notes on their social interactions and gathering their droppings.

Archie (left) stands on a dusty plain in southeastern Kenya watching the baboons, jotting notes on their social interactions and gathering their droppings.

Her work with the biomes will also help clarify whether things like obesity, fitness, immune function, mental health and fertility are influenced by what is in a baboon’s — and his friends’ — guts. And whether the makeup of those guts attracts or deters mates.

Archie’s lab, in collaboration with Tung’s, also studies how early adversity impacts health and lifespan. They’ve found that baboons born during a drought, who lose their mother early on or who have a socially isolated mother have a median lifespan of nine years, compared to 20 years for better-privileged baboons.

“We saw the survival effect and now we’re trying to figure out why. Why do animals who grow up under harsh conditions, why do they lead such short lives?“ she explains.

The list of questions the group hopes to answer is long, but so is the data set. The longer the study persists, Archie says, the more formerly impossible questions the group can tackle. The longevity of the project, along with funding from the National Science Foundation and the National Institute on Aging, has resulted in quite a prolific study. In its nearly 50-year tenure, the project’s researchers have produced more than 200 publications.

Thanks to a 15-year collection of 20,000 baboon droppings, she has proven that baboons in the same social group have similar gut biomes — the combination of good and bad bacteria that help resist disease, mediate toxins in food, make vitamins and help digestion.

Thanks to a 15-year collection of 20,000 baboon droppings, she has proven that baboons in the same social group have similar gut biomes — the combination of good and bad bacteria that help resist disease, mediate toxins in food, make vitamins and help digestion.

The study’s continuation also allows them to continue to mentor Kenyan graduate students, like the three from the University of Nairobi with whom Archie has worked, and employ individuals from the local community.

“It’s very important to us that we are supporting local scientists and supporting the community where we live,“ she says.

And it’s important that they’re training young American scientists so this study can continue for generations to come.