Fighting for Shakespeare for All

When Christy Burgess started the Robinson Shakespeare Company in 2008, the idea of the youth acting troupe one day performing in England would have been laughed off as an impossible dream.

Burgess had a hard enough time convincing people at Notre Dame’s Robinson Community Learning Center that she could sustain the program beyond one summer. If that. Difficulty raising money to stage a bare-bones production of Macbeth, and finding interested kids to be in the cast, almost brought the curtain down on the idea before it began.

She was told that the local youth who participate in the Robinson Center programs, many from disadvantaged backgrounds, wouldn’t want to perform Shakespeare. The oldest of the old-school literature wouldn’t be the way to reach them.

One person, trying to express sympathy for the challenge Burgess had set for herself, told her flat-out not to be disappointed when the attempt to start an acting company failed.

“I look forward to proving you wrong,” she responded with a smile.

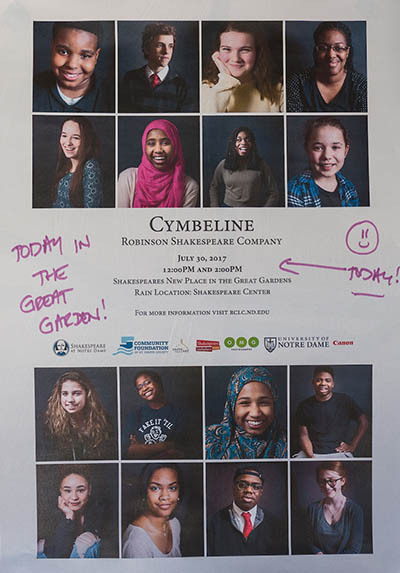

The Robinson Shakespeare Company members perform Cymbeline in the Great Garden at Shakespeare's New Place in Stratford-upon-Avon, Warwickshire, England. Photos by Barbara Johnston / University of Notre Dame.

The Robinson Shakespeare Company members perform Cymbeline in the Great Garden at Shakespeare's New Place in Stratford-upon-Avon, Warwickshire, England. Photos by Barbara Johnston / University of Notre Dame.

She’s not the told-you-so type, but Burgess could be forgiven a little gloating nine years later as the Robinson Shakespeare Company continues to exceed what even she could have envisioned when it began.

Performing in England wasn’t an impossible dream, after all, but a reality that 14 South Bend school kids from age 12 to 18 experienced this summer. They spent eight days tracing Shakespeare’s cultural influence from his birthplace in Stratford-upon-Avon to his theatrical home in London.

In the Great Garden of Shakespeare’s New Place, the Stratford-upon-Avon estate he owned for the last two decades of his life, the Robinson Shakespeare Company performed Cymbeline. They were the first group ever to perform in the space that opened last year as a landmark honoring Shakespeare’s creative legacy.

And the poster promoting their performances, adorned with photos of each cast member, went into the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust archives, becoming part of one of the world’s largest and most important collections.

Then at the Globe Theatre in London, a replica of the playhouse where many of Shakespeare’s works were performed for the first time, they were granted the privilege of an hour on stage. Glynn MacDonald, the theater’s legendary “Master of Movement,” gave the Robinson company a private lesson in the principles she has instilled in every actor who has performed there since it opened in 1997.

Each moment seemed to leave the ensemble members more awestruck than the last. They couldn’t help but reflect on how far they had come from the cramped, retrofitted former grocery store a couple blocks south of the Notre Dame campus where they embarked on this journey.

An unlikely, triumphant journey — spanning nine years, not just those eight days — for what Burgess calls “the little Shakespeare company that could.”

Velshonna Luckey always knew they could. Even in the earliest days when it looked like the doubters might be right. Luckey is the Youth Development Program Director at the Robinson Center. In the summer of 2008, she was also the primary recruiter for its fledgling Shakespeare company.

Burgess was new to South Bend back then. She showed up at the Robinson Center while looking for work around town. She hit it off right away with Luckey, who happened to be in the market for an assistant.

They started working together — Burgess as Luckey’s assistant, Luckey as Burgess’ true believer and promoter of the grand plan to start an acting company. For the first summer production, Luckey recruited about a dozen novice actors, able if not always willing participants.

“Trust me,” Burgess says, “these kids did not want to get up and go do Shakespeare at 9 am.”

“If my kids don't come out of it feeling better about themselves, or knowing more about themselves, or having a sense of accomplishment, even if we have an amazing show, I have failed as their teacher and as their director.”

— Christy Burgess

Burgess faced her own personal obstacles that summer, including so little money that she couldn’t afford a car, clocking about 80 miles a week on her bike to get the Robinson Shakespeare Company’s wheels turning. Her dedication gave her little sympathy when the students didn’t show the same commitment.

“OK, guys,” she would say when the students were reluctant or distracted in rehearsals. "Am I working for you? I need you to work for me."

A breakthrough came when she halted an exercise that had descended into individual showing off, as opposed to the team-building exercise it was intended to be. Burgess wanted to redirect their attention away from themselves and toward their fellow ensemble members.

“I had the kids go around and say one nice thing, one honest thing about each person,” Burgess says, “to give that person an honest affirmation.”

By the end of it, one boy was in tears over the praise heaped on him, with others saying how much his friendship meant to them as they handed him tissues. The practice of affirmations has become a Robinson Shakespeare Company tradition, as important to its success as anything that happens on stage.

"This is a community center, not a theater,” Luckey says, and the purpose of any program has to be youth development, a philosophy Burgess embraces with the equal fervor.

A great show is not the main goal. All the effort directed toward that end through months of rehearsals serves a larger purpose and a higher priority: the personal growth of each member of the company.

“If my kids don't come out of it feeling better about themselves, or knowing more about themselves, or having a sense of accomplishment,” Burgess says, “even if we have an amazing show, I have failed as their teacher and as their director.”

A virtuous cycle spins out of that approach. High expectations for performance and conduct motivate students to achieve more, instilling a sense of pride and responsibility to each other that elevates the end product.

During that first summer, done on such a shoestring that a $1,200 grant from the Community Foundation reduced Burgess and Luckey to grateful tears, the power of the process became evident.

“When the parents saw their kids up on stage performing Macbeth, I think that's when it happened,” Burgess says. “When they realized that these kids could do it. They can do something that most adults are afraid of, and they can do it really, really well.”

That fast, skepticism changed to enthusiasm.

“Next thing you know,” Luckey says, “you had younger and younger children wanting to have that opportunity and it caught like wildfire.”

Josh Crudup’s older brother was in that first production. Josh learned some of his brother’s lines just from overhearing him practice at the kitchen table. When Josh showed off his second-hand memorization for Burgess, she said he should join the Shakespeare company himself.

“This is an outlet for children of all backgrounds to work out their emotions, work out their frustrations, work out their disappointments.”

— Velshonna Luckey

He joined the next year. It didn’t go well.

Josh did a better job memorizing his brother’s lines than his own and Burgess finally kicked him out.

“I expect greater from you,” he remembers her saying.

Thinking back on the experience now as a high school junior, Josh says he understood even as a third-grader that the dismissal was not meant to punish, but to inspire. Her high expectations — of him, of everyone in the group — pushes them beyond their own perceived limitations.

It’s the same mentality that made Burgess believe a youth acting company could succeed when few others did, a confidence that extends to the capacity of each student, regardless of their background, to master Shakespeare in all its depth and complexity.

“We’re not changing the language,” she says. “We’re not dumbing it down.”

Josh, responding to her challenge, came back and won the monologue competition in his age group the following year. And he was one of the first to have his lines DLP — “dead-letter perfect” — for this year’s production of Cymbeline.

Many of the ensemble members have similar stories of exceeding their personal expectations and finding, in Shakespeare and the strength of the bonds between them, a path through the storms that arise in their lives.

Shyness overcome, self-doubt defeated, despair lightened, through the counsel Burgess offers above and beyond the stage and the caring culture she establishes among the ensemble members.

Ophelia Emmons joined the Robinson Shakespeare Company a few years ago at her mother’s urging as a middle school student so bashful she couldn’t imagine uttering a word in front of an audience. She’s 16 now and had a lead role in Cymbeline, progress she attributes to Burgess’s capacity to push the actors so far while holding them close to her heart.

“I’m always appreciative of the fact that she never dumbs herself down or dumbs down Shakespeare for us,” Ophelia says. “I think her great expectations for us are just examples of how great her love and care for us are.”

Precious Parker knew Burgess from drama classes she taught at her elementary school as part of the Robinson Center’s community outreach. Precious liked Burgess but wasn’t interested in Shakespeare, rebuffing her invitations to join the company.

After years of saying no, Precious signed on just before her freshman year in high school. She found it no less than life-changing. The counsel Burgess offered and the warm embrace of the ensemble — often literally with group hugs — became a guiding light that brightened her spirit.

“Being able to talk to her about things, it made me feel better,” Precious says, “because she would give me reasons why I should keep going, why I should do good things.”

Just two years since joining, Precious played a lead part in Cymbeline on land where Shakespeare himself once walked, symbolizing everything Burgess envisioned for the Robinson Shakespeare Company, on stage and off.

As Luckey puts it: “This is an outlet for children of all backgrounds to work out their emotions, work out their frustrations, work out their disappointments.”

And, in the process, achieve successes they otherwise would not have imagined possible.