Fighting to Build on Tradition

On the Navajo Nation, a territory encompassing 27,000 square miles across Arizona, New Mexico and Utah, sits a lone Catholic school — Saint Michael Indian School. There, 400 students from preschool to high school are educated in both the Catholic faith and the Navajo culture, just as the school’s founder intended in 1902.

That founder, St. Katharine Drexel, the second American-born saint, was born to a wealthy and pious family in Philadelphia. Though she could have lived as an heiress, she became interested in the unfortunate situation of Native Americans and African Americans during a family visit to the West. She became a nun with the Sisters of Mercy before establishing her own religious congregation called the Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament for Indians and Colored. She then set out to create schools for Native Americans and African Americans. In total, she founded 63 schools, 50 missions and a college, Xavier University of Louisiana.

Today, only one of the 63 schools remains in operation: Saint Michael Indian School. But the school’s president, Dot Teso, hopes to resume what St. Katharine began.

“My dream for her schools is to build more schools on the reservations in the Southwest and particularly the Navajo nation. By giving the people of this community something to hope for and by introducing donors and other people, inviting participation, we’re going to be able to build more schools,” she says. “This is basically the cornerstone of the future of her mission.”

That cornerstone is a new campus plan and new buildings, the first of which was designed by Notre Dame undergraduates.

“Our vision of ourselves in the future is an opportunity that we haven’t had, and an opportunity that we want to seize.”

— Deswood Etsitty ’93

Saint Michael Indian School is one of seven schools across the United States in the American Indian Catholic Schools Network. That network, a collaboration between Notre Dame’s Alliance for Catholic Education and the participating schools, seeks to strengthen and grow individual schools and to expand the network to include and empower additional mission schools. The long-running partnership with ACE, along with the School of Architecture’s international reputation, led Teso to believe Notre Dame was the right partner to help her grow Saint Katharine’s mission. She reached out to Father Richard Bullene, C.S.C., ’76, ’81M.Div., assistant dean of architecture, and so began a new partnership.

It was decided that a group of 10 undergraduate architecture students would spend half of a semester creating a campus master plan as a group project, and the second half individually designing the school’s first new building in decades, a gym.

Teso explains that many of the students stay at the school for upward of 12 hours a day, and some commute more than two hours to school. The campus needed somewhere students could spend time. The building could also serve as a valuable place for the community to gather.

For the Notre Dame students, the opportunity would serve as their fourth-year studio course, a portion of the curriculum meant to focus on non-Western-style architecture and which encourages students to consider regionalism and cross-cultural exchange in their designs.

The Notre Dame students focused on non-Western-style architecture and were encouraged to consider regionalism and cross-cultural exchange in their designs.

The Notre Dame students focused on non-Western-style architecture and were encouraged to consider regionalism and cross-cultural exchange in their designs.

The partnership would provide the undergraduates real-world architecture experience with a real client, but also a series of challenges. First and foremost, the students needed to learn about the native culture in order to genuinely present it in their designs. They decided to visit the school and the reservation. There, Deswood Etsitty ’93 was their guide.

“For this project, it was important for the students to really understand on an intimate level how we speak, how we relate, the way that nature speaks to us, and how that can be conveyed through a design process, and how that can be presented architecturally,” Etsitty says.

Etsitty grew up on the Navajo Nation in Pinon, Arizona. He left the reservation to attend Brophy College Prep in Phoenix before going to Notre Dame to study architecture with the hope of returning home to design buildings for his people that accurately reflected their culture.

“What you see on a reservation is in large part what the government has kind of imparted as far as these buildings,” he says. “Native people didn’t really have a say in it. But we do have our own way of building and our own design and creative philosophies with regards to how we build, and those two things never really quite came together.”

He continues, “Our vision of ourselves in the future is an opportunity that we haven’t had, and an opportunity that we want to seize.”

Today, he is a facilities planner for Indian Health Service where he plans and designs health care facilities that incorporate tribal beliefs into the construction of modern health care settings. After working 22 years in the private sector as designer and construction administrator, his focus now is working with tribes and communities to help them shape and define their healthcare environment, applying essential cultural and spiritual elements to functional healthcare design, and finding ways to integrate traditional healing practices in design.

He shared these elements with the Notre Dame undergraduates, and encouraged them to look to cultural touchstones to influence their designs of the new athletic facility.

Jenna Frantik, one of the architecture students, says, “Deswood was really influential in this project in helping us to learn and understand Navajo culture, and also how we can incorporate our traditional education in architecture from Notre Dame and incorporate Navajo tradition into that as well.”

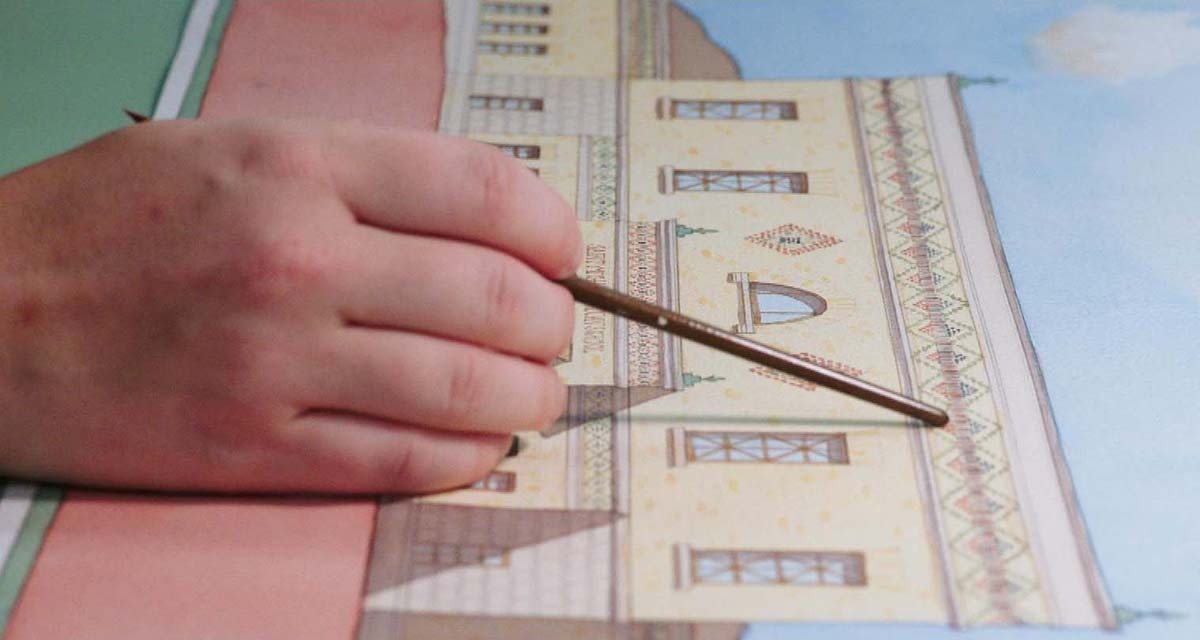

As for her design, Frantik explains she was inspired by Navajo art. “Since there wasn’t much precedent for Navajo architecture at the scale we were building, I decided to focus my design on Navajo art. I primarily looked at the Wide Ruins patterns to understand the color palette and also the designs typical of Navajo art in the area.”

“Another element that we learned about of Navajo culture is the importance of the landscape in the built environment,” she says. “In our designs, we had to tackle how to build a building of such a large scale and kind of bring that down to reflect the landscape and be a natural part of the landscape.”

At the end of the semester, Frantik and her classmates each presented their designs for the athletic facility to Etsitty, Teso and other Notre Dame and Saint Michael’s faculty. Three were selected to be shown to the community back at the Navajo Nation. The community responded favorably and has since decided to use a combination of the three designs to build its new facility. The designs selected will be made into 3D models by students at Saint Michael’s so they can be used as part of a feasibility study as phase one of the school’s capital plan.

St. Katherine established her own religious congregation to create schools for Native Americans and African Americans. Historic footage and photos courtesy of the Catholic Historical Research Center of the Archdiocese of Philadelphia.

“I hope these designs for the community bring a new sense of identity to the place. The mission of St. Katharine has really lived on in the school of Saint Michael’s, and to see this mission be continued in our gym and also in the other buildings that we proposed will really live on as her legacy,” Frantik says. “To be able to be involved in this project as a student has really shown me the power of architecture and what we create and how it will impact not only this generation but also many future generations to come.”

Etsitty hopes future generations who benefit from the new buildings will be inspired not only by St. Katharine’s mission, but also by the involvement of Notre Dame. He currently serves as the alumni relations assistant director of the Native American Alumni Board for the Notre Dame Alumni Association. He hopes in the years ahead, more Native American students, especially those from Saint Michael Indian School, will attend the University.

“I’m proud to be a part of this collaboration with my university,” Etsitty says. “It's wonderful to see Notre Dame come into Indian Country, into the Navajo Nation, and to see these students taking hold of this assignment, learning about our unique way of life, working on a real-world need in collaboration with the Saint Michael’s community, and developing meaningful solutions that inspire and will impact generations.”