Fighting to Protect Our Community

As Ed Striedl remembers it, the borough of Keansburg, New Jersey, tried to fortify against Hurricane Sandy. In the days and hours ahead of the storm, evacuation was encouraged. Locations on high ground were set aside for people to park cars. Shelters were put into place. And yet when the storm hit, destruction came in unlikely and devastating forms.

“We didn’t have the rain that we had the year before in Irene. So a lot of people got confident,” Striedl, a construction code enforcement officer and floodplain manager for Keansburg, recalls. People said to him, “Oh, you made me leave during Irene, and I didn’t have to. And now I’m going to stay because it’s not raining as much.”

But rain isn’t the only destructive factor in storms. As Keansburg experienced, storm surge, wind damage and destroyed dune systems wreaked havoc on the town. Half the structures in the borough saw between two and five feet of flooding. More than 300 homes were significantly damaged. Complete power outages lasted up to 14 days. And debris and flooding covered the seaside town for weeks after.

People fled, but in those moments when most people run away, that’s when Tracy Kijewski-Correa runs in.

Kijewski-Correa is a civil engineer and associate professor in both the College of Engineering and the Keough School of Global Affairs at the University of Notre Dame. Her work in disaster risk reduction and international development has taken her from Haiti to Indonesia, Dhaka to Dubai. In most cases, in the wake of a disaster she’s running toward the damage, hoping to document it in detail.

Tracy Kijewski-Correa

Tracy Kijewski-Correa

“I travel to the field after disasters for two reasons. One, as a civil engineer there’s really no way to validate all the things that we have to assume when we model and design a structure before it’s built. There’s only one way to test it, and that’s actually to subject it to Mother Nature. So it is our most powerful laboratory to go out into the field after disasters,” she says. “But then secondly it’s a time for us to reconnect and remember why we became engineers. You ask almost any civil engineer in the world why they became a civil engineer, and they’ll say because they know infrastructure — buildings, bridges, roads — changes lives. And when we see how much lives are impacted by the failure of those things, there’s a natural call for us to kind of reconnect with that.”

The data she and her team collect on the ground is used to validate or change building codes with the hope of creating more sound and safe structures, especially as a city rebuilds. FEMA and relief agencies also use the data to understand the depth of damage in an area.

But in studying disasters, particularly in areas susceptible to repeated incidents, Kijewski-Correa wondered if there was a better way to get ahead of a storm’s impact, not just evaluate the damage afterward.

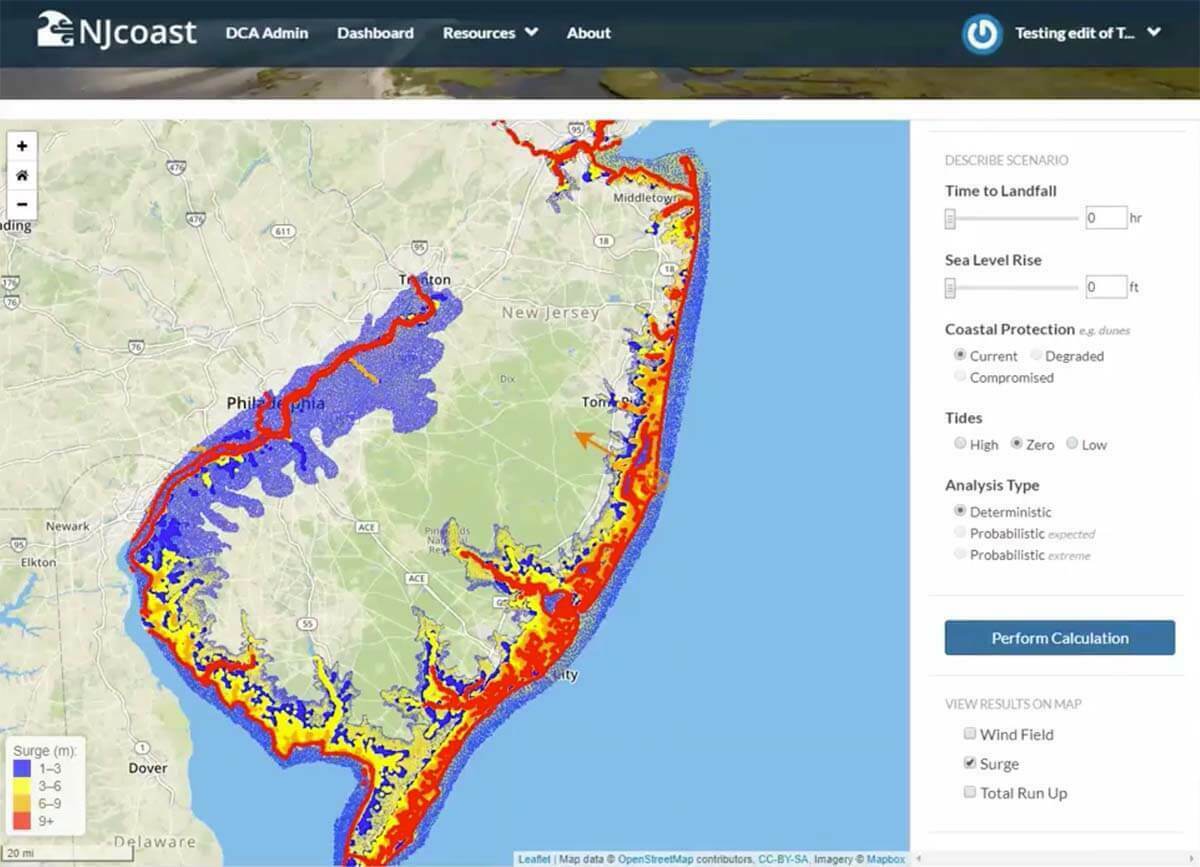

In June, in partnership with the State of New Jersey Department of Community Affairs, Kijewski-Correa launched NJcoast along with professors Andrew Kennedy and Alexandros Taflanidis at Notre Dame’s College of Engineering, a team of developers led by Charles Vardeman II at the Center for Research Computing and Notre Dame alumnus Teng Wu, a professor at the University at Buffalo. A web-based platform, NJcoast allows people on the ground to quickly access data, forecasted scenarios and emergency preparedness information so they can make better-informed decisions before an impending storm.

According to Kijewski-Correa, the Leo E. and Patti Ruth Linbeck Collegiate Chair, the simulations in NJcoast are on par with what FEMA and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers use, with exceptional accuracy, but they don’t require special software or training. It’s all accessible straight from an iPad or computer.

Keansburg, New Jersey after Hurricane Sandy

Keansburg, New Jersey after Hurricane Sandy

“NJcoast puts critical information in the hands of emergency managers and first responders as they work to prepare for and respond to hurricanes and nor’easters,” she says. “We took NJcoast very seriously, because we knew that every figure, every plot, every piece of data that we collected and made available in the system was going to be used to make decisions that could cost someone their life, but we know now will protect their lives.”

Using the same geospatial web system used by the World Bank, United Nations and U.S. State Department, NJcoast gives users access to up-to-date information regarding storm hazard projections, critical facilities, infrastructure networks, evacuation routes and more. This unprecedented access, all available in a standard web browser, will allow users to better anticipate a storm’s impact and work together to react.

Storm surge predictions in NJcoast (click to enlarge)

Storm surge predictions in NJcoast (click to enlarge)

Striedl says, “We’re hoping that we’re now going to have a tool in our hands that we can predict exactly, based on past storms, where the likely problem areas are going to be.”

Striedl’s borough of Keansburg is at risk for damage from another hurricane or nor’easter, because 95 percent of the community is in a flood plain. But they’re not the only ones. Towns up and down the coast will be better equipped to deal with their own geo-specific vulnerabilities with NJcoast. This summer, Keansburg and Berkeley township beta tested the application, and the state’s Department of Community Affairs has since made NJcoast available to users across New Jersey.

Kijewski-Correa says, “The most significant application for our work has been knowing that this toolset that’s now being rolled out across the state of New Jersey will help communities like Keansburg and Berkeley, and the 500-plus municipalities like them, finally have access to all the data they can use to make these decisions, but that currently is siloed away from them.”

True empathy for the people with whom she works is evident in all of Kijewski-Correa’s many projects, from her first disaster work after the Boxing Day tsunami in Southeast Asia, to post-earthquake work in Haiti, to reconnaissance in Texas after Hurricane Harvey. She’s able to relate to individuals and communities as she serves them. Long after her visit to Haiti, she continues to work on rebuilding the region even today.

“We talk about a force for good in the world — that’s a tagline we use a lot here at Notre Dame. I think other universities might try to grab onto that kind of tagline as well, but a lot of universities aren’t willing to go out on the front lines and be there when it counts,” she says. “You’re going to go in and when others leave, you’re going to stay. And you’re not just going to stay, you’re going to go deeper and you’re going stand with those people until they have completed that recovery. No matter how long it takes, you’ll accompany them. And that’s a big difference between a lot of universities, who might mean well but move onto the next target quickly. That’s not what we do here. We accompany people all the way.”

As New Jersey rolls out NJcoast this year, Kijewski-Correa is still there in the background, making certain they have the support they need as they fight to protect their communities. She’ll accompany them as long as they need.

To learn more about NJcoast, visit https://njcoast.us.

Questions regarding NJcoast should be directed to the NJDCA via njcoast@dca.nj.gov.

For more information on Hurricane Sandy efforts from the State of New Jersey Department of Community Affairs, please visit: